There are many parallels between the provision of rail and health services in the UK. Most obviously, we now have government-run railway operated by the private sector in the form of franchised Train Operating Companies. And we have a government-run health service, again substantially provided by the private sector in the form of self-employed GPs, dentists etc, plus hospitals with a great degree of independence which compete with each other and can and do go out of business. Both sectors are subject to competition law which can lead to the competition authorities making decisions which conflict with government policy - for instance to grant rail franchises or to merge hospitals. The following notes explain why it is extraordinarily difficult to regulate these two sectors.

On the one hand, they both contain near-monopolies. The rail industry contains a number of natural or near natural monopolies, for there can usually be only one set of tracks between stations. The health service is (quite rightly) staffed by restricted-entry professionals, and specialist hospital services need to be provided in a small number of regional centres. As a result, both sectors demonstrate lower than optimal productivity, and the quality of their service provision is often the subject of serious criticism. It is also the case that they are both heavily taxpayer funded. Successive governments have therefore been very keen to find ways of introducing competition into the sectors, so as to drive greater efficiency and improved service quality, and reduce the size of the taxpayer subsidy.

However, even putting their monopolistic characteristics on one side, it is clearly impossible to abolish all public funding and introduce unrestricted competition into either sector. This would inevitably price-out poorer members of the community, impose unacceptable social cost and - in the case of the rail system - do huge economic damage to the economy of Greater London which depends so heavily on the rush hour commuter rail network. After all, any new transport infrastructure brings with it very large externalities (i.e. costs and benefits which accrue to third parties). In the case of rail, these are mainly beneficial, allowing new housing and commercial development, and increasing land prices. That is why it makes sense for the government to build roads and railways, and then subsidise their running costs, recouping the cost through general taxation.

There is also the point that effective regulation in any sector has to ensure that price competition does not leak through into unacceptably reduced service quality and/or a reduced range of services. But this is extremely hard to do in these sectors, for what is 'unacceptable'? In rail, where is the balance to be struck? It is difficult (and maybe impossible) to ascertain the extent to which rail passengers would be willing to trade reduced quality and reduced service frequency for lower fares. And then what about the rail safety/cost trade off? In health, it is surely near-impossible to measure 'quality', let alone ascertain what trade-offs would be acceptable.

Rail - Comment

Turning specifically to railways - It is important to remember that our public transport systems create real winners in the form of those of us who own property near roads, railway lines etc. Imagine what would happen to property prices around London - or indeed in Central London - or in many other cities - if our suburban railways and Tube system were to be closed down. But no-one has yet come up with a politically acceptable way of capturing such 'externalities' via taxation. So we carry on with the next best policy which is to support 'loss-making' franchises via "subsidies" funded by general taxation.

But is "subsidies" even the right word? Christian Wolmar points out that we wouldn't use that word in the context of roads, or indeed the education system. Maybe not all taxpayers use the railway, especially outside south-east England, but they certainly benefit from it.

As Andrew Nock commented in Modern Railways in 2017:

There is no right way of structuring, funding and governing a complex public service like the railway, just a variety of wrong ones, each with its own disadvantages and advantages'.

And James Ball summarises the problem in this way:

People want rail services to be cheaper, faster, and less full. These are incompatible objectives unless taxpayers are willing to live with huge increases in public subsidies.

Click here for an introduction to utility regulation.

Before rail privatisation in 1993, all the trade-offs and compromises were resolved within and between state-owned British Rail and the government of the day, without too much reference to passengers. Privatisation then created c.100 companies where there had previously been only British Rail. Trade-offs etc are therefore now resolved through complex interactions between the Government represented by the Department for Transport (DfT), a semi-independent but still public sector Network Rail, the Office of Rail and Road (ORR - previously the Office of Rail Regulation), the private sector rolling stock owning companies (ROSCOs) who lease rolling stock to the (mainly) private sector train operating companies (TOCs). They appeared to create a degree of competition which in most cases did not really exist.

Before rail privatisation in 1993, all the trade-offs and compromises were resolved within and between state-owned British Rail and the government of the day, without too much reference to passengers. Privatisation then created c.100 companies where there had previously been only British Rail. Trade-offs etc are therefore now resolved through complex interactions between the Government represented by the Department for Transport (DfT), a semi-independent but still public sector Network Rail, the Office of Rail and Road (ORR - previously the Office of Rail Regulation), the private sector rolling stock owning companies (ROSCOs) who lease rolling stock to the (mainly) private sector train operating companies (TOCs). They appeared to create a degree of competition which in most cases did not really exist.

Most of the TOCs are franchisees - that is they have successfully bid for franchises to operate as monopolies or near-monopolies running trains along a particular set railway lines. A small number of TOCs compete with the franchisees as open access operators - see further below.

Secretary of State Chris Grayling announced in late 2017 that he favoured the development of new 'public-private partnerships' between TOCs and Network Rail. It's a fine idea in principle but adds further complexity to a franchising system that was already truly baffling.

Secretary of State Chris Grayling announced in late 2017 that he favoured the development of new 'public-private partnerships' between TOCs and Network Rail. It's a fine idea in principle but adds further complexity to a franchising system that was already truly baffling.

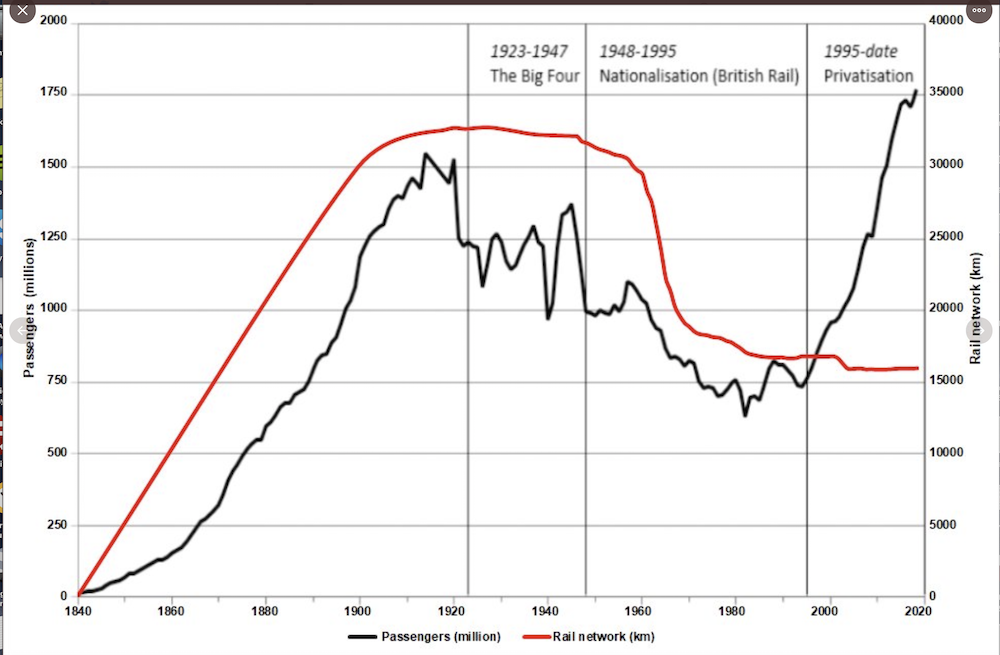

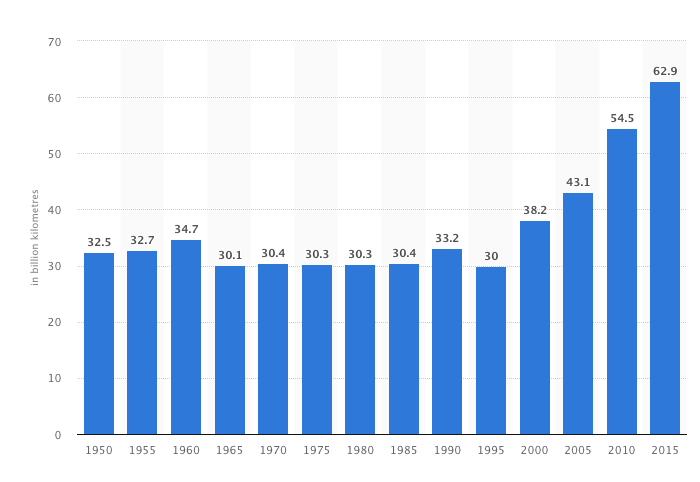

The main benefit of privatisation is that the policies of the TOCs are strongly informed by what customers want. And passenger numbers have soared since privatisation in 1995 - see chart on the right. (The vertical scale is passenger-kilometres.) It is far from clear, though, how much privatisation and good regulation have contributed to this. Passenger growth in recent years has been strongly correlated with employment. And other (still state-owned) railways have seen similar increases in passenger numbers. There are some key facts towards the end of this note.

Certainly no-one suggests that the ownership and regulatory structure is in any sense ideal, and it has changed a lot over the years as successive governments have grappled with the tensions inherent in the system, without wanting to undertake the embarrassing and/or expensive task of renationalising the system. One recently retired Network Rail Chief Executive commented that his tenure had been marked by the Department of Transport 'pulling the strings from behind the curtain'. And privatisation has certainly failed to deliver the reductions in subsidies that were envisaged by its supporters.

In the end, the 2020 COVI-19 pandemic and associated economic crisis sounded the death knell for franchises, though it currently remains far from clear what will replace them.

It should be remembered that franchising offered competition only at the time of bidding for franchises - i.e. every few years - and that the cost of bidding has increasingly led to there even being relatively little competition for individual franchises. My own personal view is that the franchising process was too strongly driven by HMG's determination to extract as much money as possible from franchisees - or pay as little 'subsidy' as possible. So incumbents were forever worried about losing their businesses altogether (competition leads to less abrupt change in most other sectors) and potential franchisees were driven to cut costs as much as possible. They sometimes planned to employ too few drivers and on-train staff etc. - and so canceled too many trains - and/or they took too many financial risks. Further detail follows:-

Current Regulatory Issues

1. Railway Financing & Financial Risk

Railway financing is very complicated. Annual fare increases, every New Year, inevitably attract much negative publicity. I have attempted an introduction and some analysis in this separate web page. The key message is that annual fare rises are mainly determined by the government when it decides how much to subsidise the railways.

Some railway fares are subject to price control. Follow this link for an introduction to price controls and a brief mention of a 2014 Government interference in the process which led to higher fares for some, and reductions for others.

Some argue that the UK railway industry is now too obsessed with passenger safety and this leads to excessive costs, including when planning new infrastructure. Passengers are, however, no doubt relieved that there have been no fatal passenger accidents since 2007.

There is a somewhat unresolved issue about the amount of financial risk that should be borne by the franchisees. They cannot for instance manage the (substantial) impact of the economy on passenger numbers so they argue this risk should in principle be held by (a rather reluctant) government. But most other private sector companies obviously have to manage similar risk themselves, and can accordingly fall into liquidation. Taking a similar approach at franchise time would clearly significantly reduce the amount that a successful franchisee would be willing to pay for the franchise, so it has become accepted that companies can hand back their franchises to the government rather than be forced into financial disaster.

This has happened three times on on the East Coast Main Line.

This has happened three times on on the East Coast Main Line.

- In 2005, GNER signed a £1.35bn, 10-year deal in what was then the biggest contract in European railway history. One year later it was stripped of the route.

- In August 2007, National Express agreed a £1.4bn deal, but then handed the franchise back to the government in 2009 amid the financial crisis.

- The railway was then government-run until Stagecoach and Virgin's £3.3bn 2015 bid for an eight year franchise with the bulk of the bill to be paid after 2020. But forecast passenger growth failed to materialise and the government announced that the franchise would be yet again be terminated - this time three years early - forfeiting maybe as much as £2bn of franchise receipts in doing so.

The government said that this was in order to end the operational divide between track and train so as to create the first of a new generation of integrated regional rail operations, and so improve performance, particularly by cutting delays, which were quite frequent on that line. ECML pointed out that Network Rail were failing to provide certain infrastructure improvements. But it looked very much like a cosy unjustified bail out of a large private sector company when the rest of the country was suffering from austerity policies. The stock market certainly thought so. Stagecoach - the main shareholder - saw its share price rise 12%! It also looked like a strange return to the pre-nationalisation structure of regional railways, but without any clear plan or serious public consultation process.

Edward Lucas, in the Times, noted that "[The government] has just bailed out two of the richest men in the country to the tune of £2bn." He was referring to Virgin's Richard Branson and Stagecoach's Brian Souter.

However, to be fair to Virgin Trains (and the Government) it should be noted that the company had invested more in the two years in which it operated the route than the previous state-owned railway did in its five-and-a-half years running it. And Virgin Trains returned 30% per year more to taxpayers during its time running the route than did its predecessor, making it a much better-value option for taxpayers. By April 2017, barely two years into its running the franchise, Virgin Trains had returned some £525m to taxpayers from running the East Coast Main Line - more than half as much as the state owned railway did in twice that length of time.

These facts encapsulate the main problem with nationalisation. It is not that the managers or staff are any less able. It is that the Government tends to invest less and drive productivity less fiercely, which feels good in the short term but eventually leads lower efficiency and lower quality. It doesn't have to be thus - but it generally is.

The next franchisee to regret its investment was First Group who were reported, in late 2018, to want to renegotiate its contract to run South Western services out of Waterloo, The contract protected it against falling income as a result of falling central London employment, but not against changes in working patterns as a result of flexible working, such as reductions in five day working and less peak hours travel. One could not help but reflect, however, that South Western's troubles were pretty limited compared with those facing many other private sector companies. First Group clearly found risk-taking to be attractive as long as their was no downside risk!

And then the Covid-19 coronavirus struck in early 2020, eliminating most rail travel for several months. The government had no option put to cancel all rail franchises and to put all train operators on management contracts for at least 6 months.

For another perspective - Michael Moran published a critical review of rail privatisation in 2017.

2. Open Access

Open access was supposed to be the big gain following privatisation - true competition along the main railway lines with successful franchisees being kept on their toes by small niche operators offering cheaper (maybe slower) services and/or services to less popular destinations and/or better service, such as dining cars. They wouldn't pay their 'fair share' of the infrastructure cost - only the marginal cost of adding additional trains - but they are not allowed to be 'revenue extracting' - i.e. they are supposed to attract additional passengers, not steal them from the franchisee.

This latter condition was initially interpreted quite restrictively by government and ORR who together ensured that nothing was to be allowed to come between the franchisees and their monopoly profits, which in turn generated big payments to the government. Very few operators have accordingly been allowed open access. But ORR seem recently to have become rather more keen on open access, much to the irritation of the Department for Transport. This is in part an Arup report in 2009 showed that, where passengers have a choice of operator, fares were kept down and service frequency and other quality measure improved.

The current situation is as follows:

- Heathrow Express is one open access operator - but a very special one. Somewhat ironically, they complained that ORR intended to allow TfL's Elizabeth Line to access the Heathrow Express spur to Heathrow without paying a large enough access charge, but their challenge was dismissed in the High Court.

- A service from Shrewsbury to London was subject to so many restrictions that it never attracted sufficient passengers.

- And in December 2014 ORR rejected an application by Great North Western Railway to run an off peak service between London Euston and Blackpool, Huddersfield and Leeds.

- So there are currently only two true open access operators, both running up the East Coast from London - to Bradford and Sunderland (Grand Central) and Hull (Hull Trains). They together carry c.25% of east coast passengers from York to London, and 40% from Doncaster. Grand Central is owned by Arriva which is in turn owned by Deutsche Bahn. Hull Trains is owned by First Group.

- Interestingly, the East Coast franchised operator responded to this competition by improving the frequency of its services to e.g. Grantham and Northallerton.

- And consumer body Transport Focus reported in 2018 that the three competing east coast operators were rated, by customers, as the three best operators in the UK.

- But ORR issued a licence to First Group in May 2016 to run five trains a day, each way, between London and Edinburgh, on condition that there is no first class accommodation and that the average single fare is £25. The new services will not start until 2021 and will clearly offer interesting competition for the low cost airlines that currently fly the Edinburgh - London routes.

- Overall, however, open access accounts for only c.1% of all passenger journeys.

- Great North Western Railway has been given permission to launch open access passenger services between London and Blackpool in early 2018.

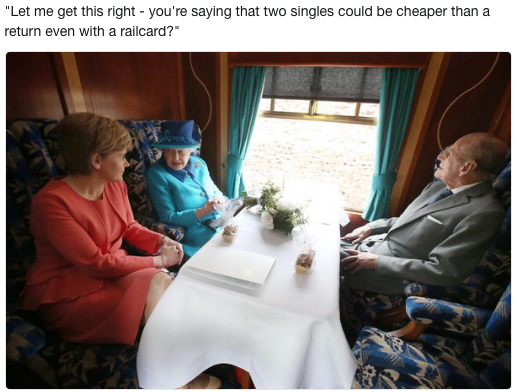

3. Complex Fare Structures

3. Complex Fare Structures

It is of course a fundamental feature of competition that it drives down prices and drives up quality on average. But it carries no guarantees about which particular customers or providers may win and lose from the process - and the losers can be very vociferous. In the case of railways, there are frequent complaints about the complexity of fare structures - the result of franchisees:

- introducing targeted incentives aimed at attracting customers from other franchises and from competing transport operators such as coaches and airlines, and

- offering targeted fare reductions aimed at those who who are willing to travel in less comfort and/or on less popular trains and/or book in advance.

The resultant complexity is unpopular, not least with occasional travelers, but the low fares certainly appeal to students, families, the retired and many others who happily trade speed and flexibility for the some remarkable cost-savings.

- As of October 2016, the lowest advance fare from London to Newcastle was £26.40 with a railcard. The highest walk-on first class fare was £222.00.

- The equivalent London Paddington-Bristol Temple Meads fares were £19.90 and £174.50, and there was a £7.90 fare available on a through train from Waterloo.

- David Laws MP tells the nice story that he once undertook a train journey with three other Ministers. One (a Treasury Minister!) paid £260. Another, the Transport Secretary, paid £160. Mr Laws paid £155. The fourth had gone online and paid £39. There's a lesson there ...

Other good deals are well hidden - perhaps deliberately. Here is one example:

- I saw a complaint that there were no cheap advance fares available between Glasgow and Oxford, which surprised me, especially as I found that it was true. But I also found that huge savings could be made if a Glaswegian bought a ticket to a station in the West Midlands, and then another - for the same train - on to Oxford.

The industry announced a review of fare structures in 2018.

Reports, Reports ...

It is clearly quite impossible to organise this complex, highly subsidised and essentially monopolistic industry in a way that encourages competition (to attract passengers) whilst providing simple, comfortable, reliable services and easy to understand services 24/7 - as required by many passengers. But successive governments and regulators are forced to keep up the pretence of seeking this holy grail by ordering the production of report after report. Here are some examples, together with brief mentions of the problems that often catalyse the reports.:-

DfT used to frequently complain about ROSCO profits which are achieved, they feel, as a result of over-charging the TOCs who lease the (sometimes very old) trains from the ROSCOs and then pass on the cost to the Government (through reduced franchise payments) or to passengers through fares. The Competition Commission (the CC - the CMA's predecessor) looked at this leasing market and reported in 2009. The CC pointed out that the ROSCOs' profits could not have been foreseen when they were created and that the solution was now in DfT's hands. They could, for instance, lengthen the franchise lengths and so encourage both the ROSCOs and the franchisees to invest in new rolling stock. DfT have not yet taken this option.

DfT used to frequently complain about ROSCO profits which are achieved, they feel, as a result of over-charging the TOCs who lease the (sometimes very old) trains from the ROSCOs and then pass on the cost to the Government (through reduced franchise payments) or to passengers through fares. The Competition Commission (the CC - the CMA's predecessor) looked at this leasing market and reported in 2009. The CC pointed out that the ROSCOs' profits could not have been foreseen when they were created and that the solution was now in DfT's hands. They could, for instance, lengthen the franchise lengths and so encourage both the ROSCOs and the franchisees to invest in new rolling stock. DfT have not yet taken this option.

ORR published a number of reports in and around 2015 which were hugely critical of Network Rail's performance, citing frequent project delays and cost over-runs, including one of 113%. The construction projects were also criticised by passengers and the media for being too disruptive to existing services. The Government, too, expressed severe concerns, and temporarily suspended work on the upgrades of two of the UK's most congested lines. Partly as a result, Dame Colette Bowe led a review which recommended that ORR should have a greater role the planning of Network Rail's major infrastructure projects. DfT were considering how to respond to this suggestion. I do not know what they concluded.

The CMA has from time to time carried out investigations into the letting of new franchises (which often involve mergers) when they threaten to reduce competition on short stretches of lines. There was, for instance, a fairly brief investigation into the provision of rail services between Peterborough and Grantham and Lincoln as a Stagecoach dominated franchise was allowed take over the East Coast Main Line, even though Stagecoach already ran the only other rail services between those cities. This seemed a bit of a sledgehammer to crack a small nut - especially as much of the rest of the network (and much of the rest of the East Coast Main Line) already had no competition whatsoever - but the issue obviously mattered a lot to a number of passengers, and the CMA have a pretty good track record in handling these small investigations sensibly and efficiently. - as they did in this case.

This 2015 blog by Dieter Helm is an excellent review of railway industry performance, and what might be done about it.

CMA Review The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has carried out a policy project (not a formal investigation) into the scope for greater rail competition for passengers. Its report was published in 2016 and called for the government to encourage competition by increasing the number of open access services (see above) or by splitting up franchises. In the longer term, the CMA recommended the more radical option of scrapping the franchise system in favour of licensing multiple operators on the main intercity routes.

Nicola Shaw has reviewed the future shape and financing of Network Rail. She recommended in 2016 that NR should:

- cease regarding the train operators as its principal customers and instead focus on the needs of passengers

- demolish its top-down, centrally-driven structure and devolve more autonomy to those more in touch with local rail networks (with each 'route' being regulated by a newly-empowered ORR)

- focus on meeting the challenges of continued rapid growth in use of the network, including

- improve connections between major Northern cities rather than continue to prioritise their connections to London.

She also recommended that the Government should develop and maintain a long-term vision for the industry. (Don't hold your breath!)

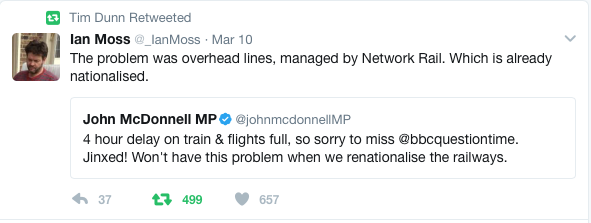

Performance problems in 2016/17, mainly driven by industrial action over the introduction of guard-free trains, led to media and political pressure to take the railways back into private ownership. It was therefore entertaining to see the Shadow Chancellor blame the private sector when a problem with state-owned infrastructure led to his missing an appearance on BBC Question Time - see Twitter exchange on the left.

Performance problems in 2016/17, mainly driven by industrial action over the introduction of guard-free trains, led to media and political pressure to take the railways back into private ownership. It was therefore entertaining to see the Shadow Chancellor blame the private sector when a problem with state-owned infrastructure led to his missing an appearance on BBC Question Time - see Twitter exchange on the left.

Similar misconceived criticisms of Virgin Trains were aired in September 2018 when problems with Network Rail's equipment delayed delegates returning to London from the Labour Party annual conference in Liverpool.

There was huge disruption in and after May 2018 when the industry was found to be far from ready for significant timetable changes. Almost 800 trains a day were cancelled. The regulator's report into the disruption spread the blame fairly widely but pointed out that Transport Secretary Chris Grayling (or his officials) had contributed to the problems by delaying key decisions.

Mr Grayling denied responsibility for the problems, arguing that he had had little choice but to accept the assurances of the industry that all would be well when the new timetables came into force. He had clearly not heard of the Prevention Paradox which encourages risk-taking in organisations such as Network Rail for fear of being blamed for being over-cautious when planning project timescales etc. But he did announce - surprise! - another inquiry (This time chaired by Keith Williams) into the future of the railways.

2018 also saw considerable disruption of the Northern and Southern franchises caused by industrial action by train staff who objected to losing their responsibility - as 'guards' - for operating train doors and instead having more passenger-focused duties.

- Their ostensible concern was for train safety but there were in truth very few occasions when the actions of a guard had made a difference in the case of a potential accident - and other instances where a guard's failure had caused an accident. And they received no support from official bodies, including the Railway Accident Inspectorate, all of whom noted that there were already loads of UK trains, including on the London Underground, which operated perfectly safely with no staff other than drivers.

- This, of course, was at the heart of the guards' concerns. They foresaw the time when many commuter trains would operate without on-board staff other than driver.

- The strikes were also a nice example of employees benefitting - or hoping to benefit - from the monopoly power of their employer. The latter could survive the strikes because there was usually no other train service available, not were passengers easily able to switch to other modes of transport in busy built up areas such as around London and the southern Lancashire cities.

It was interesting, against this background, that 2018 saw the first mainline trains operating under 'driverless' computer control in order to ensure reliability on the new very busy Thameslink tracks north of London Bridge. Many London underground trains had of course been under automatic control for many years, and some (such as the Dockland Light Railway) had no 'driver' at all.

London Underground

Please check out this separate web page if you are interested in Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Agreements Arbitration.

Rail: Key facts:

- Privatisation and competition have between them undoubtedly encouraged many customer-focussed improvements in the industry, improvements which could in theory have been achieved under state ownership, though probably not in practice, if only because of insufficient investment by cash-strapped governments. But they did not initially reduce the net cost to the government. Total subsidy in 1988-9 was £446m, or £870m in 2014 prices, compared with £3,800 million in 2014-15.

- The subsidies - and associated railway infrastructure investment are highly skewed towards the South-East of England. Northerners complain, with some justification, that they receive only one-seventh of transport funding per head compared to London.

- Passenger kilometres rose from 34.3 billion to 62.9 billion, so ...

- ... the subsidy rose, in real terms, from 2.5p to 6p per passenger km.

- Within this figure, train operators actually paid the government £0.03 per passenger mile, compared with receiving £0.002 ppm in 2009-10. The balance, around £0.098 ppm was a large payment to the infrastructure operator, Network Rail.

- Follow this link for further information about railway financing.

- There were 1,650 million passenger journeys in 2014 compared with 800 million twenty years earlier.

- Privatisation/competition fans claim that these increases were due to their policies. But the truth is almost certainly more complex, not least because passenger numbers are strongly correlated with the strength of the economy.

- There was a slight decrease in passenger numbers in 2017, especially in the South-East of England. This may have been because of more home-working and/or car driving becoming relatively less expensive once politicians had relegated the annual fuel duty escalator to history. But passenger numbers appeared to be increasing again in 2018.

- There were 47 daily services from Manchester to London (and 47 in the other direction) in 2014, compared with 17 twenty years earlier.

- Rail freight volumes have been declining for many years, but appear to have stabilised in 2017.

- HS2 (High Speed 2) is a new high speed railway line that is to be built between London and Birmingham and then on to Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds. It is a controversial and very expensive (£50 billion) project that cannot be justified on pure economic grounds but is a leap of faith by national politicians - but that has been true of so many large and successful infrastructure projects. (HS1 connects London St Pancras International with North Kent and the Channel Tunnel.)

- The new (Macron) French government is concerned that SNCF is subsidised by €14 billion a year, and is 30% more expensive than its neighbours whilst providing poorer service.

- As this chart shows, the length of the UK rail network has not increased despite rocketing numbers of passengers. No wonder trains are crowded!