The most obvious way to stop firms gaining too much market power is is to prohibit mergers which seem likely to result in a substantial lessening of competition. This leads to the most common piece of competition jargon:- 'the SLC test' as in "did they find an SLC?".

Significant mergers where the companies operate in several EU member states are scrutinised by the European Commission. Mergers where the 'parties' operate in the UK are scrutinised by the CMA, if necessary (post-Brexit) in addition to the Commission.

There is sometimes a case for prohibiting a UK merger on non-competition grounds - for instance to stop a potential enemy acquiring a defence manufacturer. These public interest cases are summarised here.

All competition regimes exempt smaller mergers from scrutiny, although the test of size varies from country to country. In the UK, mergers are exempt from scrutiny if the turnover of the firm being taken over is £70m or less and the combined firms will have no more than 25% market share.

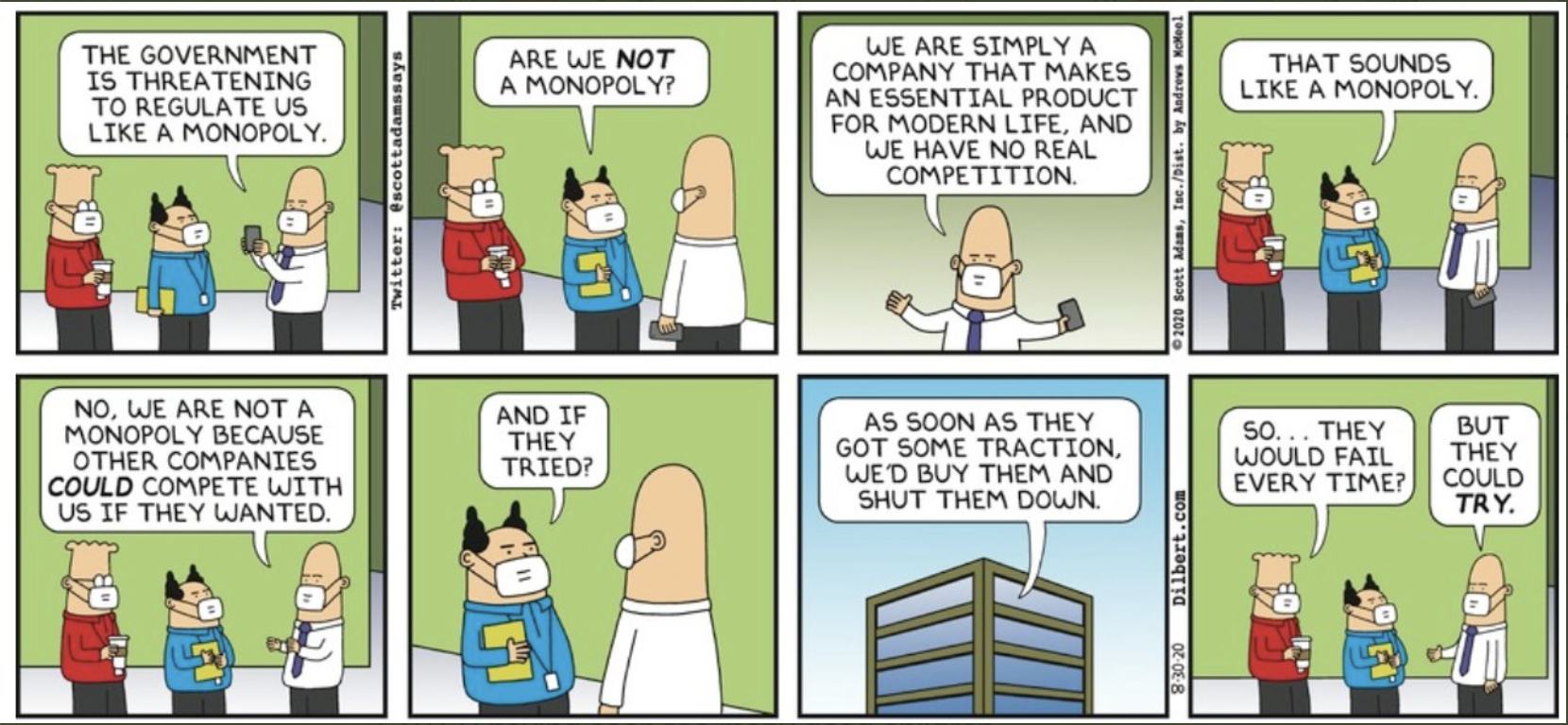

In is interesting, however, to note that both the German and Austrian governments have introduced a transaction threshold above which high value takeovers of small companies may be investigated. The aim is to protect tech disrupters which may have a small market share but a high market value. It would not be good if it was too easy for an existing large competitor to swallow them up so as to neutralise the danger from the disruption. Dilbert nicely summarised the need for this provision in this cartoon:

Two Stage Process

All competition regimes operate a two phase review process for larger mergers, in which they endeavour to sift out (and so approve) those mergers which do not appear problematic, reserving detailed scrutiny for the minority which might lead to SLCs. Most countries (including the UK) allow the phase 1 sift and the phase 2 detailed scrutiny to be carried out by the same authority. This leads to the inevitable suspicion that - having identified a potential problem - the same authority will want to prove that its initial suspicions were justified, especially as an understandable response to the companies' likely complaint that the phase 1 decision was totally incompetent and unjustified.

There is, so far, little evidence that this problem is to be found in the UK. In the UK, there are typically phase 1 reviews of around 200 mergers a year, but only refers 10 or 15 proceed to phase 2, at which a good few are cleared. Overall, therefore, the UK regime manages to be both professional and unobtrusive.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) follows a fairly standard process for all phase 2 merger investigations, which usually need to be completed within 24 weeks:

- The CMA identifies possible theories of harm - i.e. ways in which the merger might lead to a harmful outcome. It then identifies what evidence would be needed to demonstrate (in the case of each theory) that harm would indeed be the most likely result. This helps to focus the inquiry because the CMA can look for particular evidence, rather than ask every question that comes to mind. Then, if the evidence is found, remedial action can be taken - or, if the evidence is not found, the merger can be cleared.

- The CMA then issues an issues statement which summarises the possible theories of harm and other issues that it intends to consider during the inquiry. The statement doubles as an invitation to third parties (any interested companies, organisations or individuals other than the merging companies) to comment on the merger and submit evidence to the CMA. The main parties to the inquiry (the merging companies) and third parties may also comment on the issues statement if they wish - especially if they think that the CMA may have missed a possible theory of harm, or identified any issues which are in practice not likely to be relevant.

- The CMA seeks submissions from the main parties. It also requests the submission - from any person - of any evidence and information which it thinks might be helpful.

- The above steps generally take 5 or 6 weeks, following which the CMA analyses all the submissions and evidence in considerable detail and sends a number of working papers to the main parties. These papers summarise the CMAs thinking on key issues, so that the main parties can if necessary challenge the thinking before the CMA's views become too firm.

- About 13 to 16 weeks into the inquiry, the CMA issues its Provisional Findings (PFs) - a lengthy and detailed document which summarises the evidence and analysis which has persuaded the Commission to reach a provisional view that there is, or is not, likely to be an SLC. If there is no SLC then that is the end of the matter, although the CMA will in due course a publish a more polished Final Report

- But if there is an SLC then the inquiry in principle proceeds along two parallel tracks:

- The main parties sometimes - but not always - try to persuade the CMA to change its mind either by submitting crucial new evidence or by persuading the CMA that its analysis was misguided.

- This happened in 2023 in the case of the proposed Microsoft/Activision merger. The CMA was worried about two markets:- consoles and cloud gaming services. Evidence submitted after PFs persuaded the CMA to stop worrying about consoles, but they remained minded to prohibit the merger because of its effect on the users of cloud gaming services.

- This change of mind was not, as was suggested by one commentator, "something you would rather die than do". It was in fact the way that good, independent regulation is supposed to work.

- The inquiry separately enters its remedies phase as the CMA and the parties discuss how the SLC problem (if confirmed) might be remedied. The obvious remedy is to prohibit (or reverse) the merger. But the merger can sometimes be allowed to proceed subject to conditions.

- The inquiry is then formally concluded by the publication of the CMA's Final Report which confirms (or otherwise) the existence of an SLC and summarises the remedy which the CMA intends to impose on the parties to the merger.

- It is sometimes necessary to discuss and finalise a detailed remedies package, especially if the merger is being allowed to proceed subject to conditions. This can take some time but, if agreement cannot be reached, the CMA will impose a detailed remedy by issuing a formal Order, which has the force of law. See the next section for further information about remedies packages.

Remedies

As noted on the 'interesting issues' webpage, structural remedies (e.g. banning a merger) are much preferable to behavioural remedies, under which the merging companies will make all sorts of apparently binding promises to behave properly in future so as to enable an otherwise objectionable merger to proceed. The trouble is that such promises are hard and costly to monitor and, some years later, hard to enforce, especially when circumstances have changed.

Behavioural remedies experts generally follow these sensible rules:

- Be precise: Avoid generalisation such as “fair, reasonable, non-discriminatory”

- Avoid circumvention: design remedies so that firms cannot find their way round them:

- In particular, remember the PQRS trade-off. Those with market power can make money by any combination of raising prices, cutting product quality, providing an unnecessarily limited range of products, and providing poor service. It is seldom possible effectively to control only one (or two, or three!) of these.

- Consider, too, whether the remedy would work if the firm were to launch new products, or changes specifications, attract different customers, or enter new markets?

- Limit distortion as far as possible. Try in particular to avoid remedies which override competitive market signals or encourage adverse behaviour. Explicit price controls, for instance, make it harder for new competitors to enter the market.

- Ensure active monitoring and tough, speedy enforcement:

- Avoid information asymmetries (i.e. poorly informed customers), and complexity.

- Be aware of specification & design risks such as changes in the market, input costs, or technology.

A good example of an ineffective behavioural remedy was that offered by Rupert Murdoch when he persuaded the British authorities, in 1981, to allow him to own both The Times and The Sunday Times. In order to do so, he undertook that the editors would not be appointed or dismissed without the approval of the majority of a number of independent national directors - an apparently strong commitment. In practice, however, he continued to dismiss and appoint as he wished (including sacking well-regarded but independent minded Times Editor James Harding in 2012) for no editor could possibly survive unless they had his confidence. In a submission to the 2012 Leveson inquiry into press standards, the independent directors wrote: 'We see our presence as the editorial equivalent of a nuclear weapon - a deterrent to possible proprietorial interference, and therefore reassuring for the two editors.' But they conceded that their functions were limited, as it was implausible that a proprietor with strong views would propose an editor with very different views and 'similarly the removal of an editor may be achieved by means other than dismissal'. Put another way, there was no conceivable circumstances in which they would fire their nuclear weapon, so it was no weapon at all. And the directors are hardly truly independent as they are (I understand) appointed and paid for by News International.

In this context, it is perhaps worth mentioning the 1986 Guinness/Distillers merger which was not, in the end, referred to the CC's predecessor body. However, in the course of the controversial and acrimonious takeover battle, Guinness promised that a Scottish chairman would be appointed for the whole business, whose head office would be located in Edinburgh. These 'assurances' (which were not legally binding) were immediately reneged on when the takeover was completed. It is perhaps interesting to speculate what would have happened if the merger had been considered by competition authorities. First, the headquarters assurances would, if appropriate, have been turned into legally binding undertakings - almost certainly time-limited. But it is possible that they may not have been felt relevant to the decision whether or not to allow the merger to proceed. And, nowadays, the CMA cannot consider wider 'public interest' issues but can only examine the competition aspects of a merger, so they would not take any interest in the location of a head office etc.

The Takeover Code

Companies that bid to acquire UK companies whose share prices are quoted on a stock exchange must comply with the complex rules in the Takeover Code, which is enforced by the very powerful Takeover Panel - a statutory body. This system, which is quite separate from the merger control summarised elsewhere in this note, is designed to ensure that shareholders are treated fairly, are not denied an opportunity to decide on the merits of a takeover, and are afforded equivalent treatment by an offeror.

Evaluations

The following reports contain useful summaries of some interesting UK merger cases, and give a good feel for the issues which need to be considered by competition authorities when deciding whether or not to allow certain mergers to proceed. Both reports are on the CMA's website.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers evaluated 10 Competition Commission merger cases and their report was published in March 2005.

- Deloittes reviewed 10 post-Enterprise Act merger cases and their report was published in March 2009.

Interesting Cases

The Competition Commission in 2009 blocked the proposed video on demand (VOD) joint venture between the BBC, ITV and Channel Four Television also known as ‘Project Kangaroo’. Critics later accused the Commission of having prohibited the creation of a British Netflix.

The Commission's concern was derived from evidence that UK viewers particularly valued programmes produced and originally shown in the UK and did not regard overseas content as a good substitute. The project would clearly remove competition for the distribution of UK content so the Commission concluded that viewers would benefit from better VOD services if the parties - possibly in conjunction with other new and/or already established providers of VOD - competed with each other. The Commission was correct in that UK viewers eventually benefitted from intense competition between Netflix, Disney Plus, Amazon Prime and other VOD providers. We will never know whether Kangaroo (which would not initially have faced much competition) would have succeeded in that international market. I myself suspect not.

The proposed merger of two large mobile phone operators (Hutchison Whampoa-owned Three and O2) would have reduced the number of such UK operators from four to three. (The others are BT-owned EE (including Orange and T-Mobile) and Vodafone.) One would expect such a merger to lead to reduced competitive pressure and increased prices, as happened in Austria following a similar merger, so it was not surprising that the European Commission refused to allow the merger to proceed. The decision was annulled in May 2020 by the EU's General Court but the parties must have realised that a more careful re-examination of the merger would again lead to it being prohibited, so they abandoned the transaction.

In 2023, however, the two smaller operators - O2 and Vodafone - announced that they would like to merge in the UK only. The CMA will rule.

Across the Pond, the New York Times printed this interesting editorial in April 2017, following an ugly incident on a United Airlines flight:

There is no mystery why air travel has gotten so ugly. Four large airlines — American, Southwest, Delta and United — commanded nearly 69 percent of the domestic air-travel market in 2016, up from about 60 percent in 2012, according to government data.

Those numbers actually overstate how much competition there is. Many people have only one or two options when they fly because the big airlines have established virtual fortresses at their hub airports. United, American Airlines and three regional airlines affiliated with them served nearly 80 percent of passengers at O’Hare last year. Disgruntled travelers may howl on Twitter or send furious emails, but airline executives know their bottom lines are for the moment secure. It was not surprising that none of the Big Four made a list of the 10 best airlines in the world that TripAdvisor published on Monday based on passenger reviews. Two smaller companies did — JetBlue (No. 4) and Alaska Airlines (No. 9).

Much of the blame for the increased industry consolidation rests with antitrust officials in the Obama and Bush administrations who greenlighted a series of megamergers between airlines like American and US Airways; United and Continental; and Delta and Northwest. In addition, the Department of Transportation has historically been reluctant to regulate the industries it oversees — an unwillingness that persists in the Trump administration. ... As long as the big airlines face neither rigorous competition nor a diligent government watchdog, they will be able to treat customers like chattel and get away with it.

The 2018 Sainsbury's/Asda merger is discussed here.

The 2018 Mirror/Express Newspapers merger was allowed by the CMA both as a regular merger case and also following a public interest reference from Ministers concerned about newspaper plurality and editorial independence.

The CMA blocked the 2023 proposed purchase of Activision by Microsoft. Both companies were furious. "The CMA's decision rejects a pragmatic path to address competition concerns and discourages technology innovation and investment in the United Kingdom." (American companies often underestimate the power of the CMA, believing that it would not dare take on such huge companies.) But competition experts were not so critical, not least because the EU competition authority was yet to opine, and might well agree with the CMA, whilst the American Federal Trade Commission had already begun legal action to block the deal. The EU eventually cleared the deal, subject to conditions. The US litigation continues.

The CMA's decision also demonstrated that its post-Brexit freedom might well allow it to be tougher than its old colleagues in Brussels rather than somewhat softer, as some had expected.

Further Reading

The CMA's Alex Chisholm presented a very good review of merger control issues in 2014. The text is here.