The CMA Market Investigation

Following years of concern about rising energy prices and possible tacit collusion in the energy market, Energy Secretary Ed Davey wrote to the regulators Ofgem and the CMA in February 2014, raising questions about the dominance of British Gas. The full text of his letter to Andrew Wright, chief executive of Ofgem, is below - emphasis added:

Dear Andrew,

Many thanks for our meeting on Monday concerning the annual energy market assessment which is being carried out by OFGEM, OFT and CMA. As we discussed it is vital that your work is clearly independent and I want to reiterate that I want you to feel that you can recommend any one of a range of things ranging from no action to a full market investigation reference.

I am also keen that in making your recommendations you take into account potential impacts on investment and hence security of supply as this clearly significantly affects GB consumers.

However I want to reiterate that there are three areas which I am particularly keen you focus on. These issues which could have significant benefit for the consumer have had little if any focus in public discussions on the energy market and the competition assessment.

The gas supply market

Most commentary has looked at alleged problems in the electricity market. These include the benefits or otherwise of vertical integration, the liquidity and transparency of the wholesale electricity market and whether there is a case for reintroducing a power pool. As you know OFGEM and the government have been acting on many of these issues. However for the 85% of households who are connected to the gas grid two thirds of their energy bill is accounted for by gas rather than electricity.

The gas market has little vertical integration and analysis of the profit margins of the energy companies shows that the average profit margin for gas is around three times that of electricity. For some companies the profit margin is actually more than 5 times the average profit being made on supplying household electricity.

There is also evidence that British Gas, the company with the largest share of the gas domestic supply market, has tended to charge one of the highest prices over the past 3 years, and has been on average the most profitable. I attach a short analysis note highlighting some of this evidence. If the profit margin in the domestic gas supply market were similar to that in the domestic electricity market the average saving per household per annum could be up to £40.

Clearly you will wish to consider whether this is prima facie evidence of an issue in the market and so whether it merits a market investigation reference with the whole gamut of potential remedies that could follow including a break up of any companies found to have monopoly power to the detriment of the consumer. Alternatively you may of course conclude that no action is needed or potentially some intermediate measure which can be taken by the sector regulator.

Interconnection

Analysis consistently shows that Great Britain is relatively poorly interconnected to other power markets at 5% of capacity compared to a more optimal percentage of around 10%. Recent National Grid estimates have indicated that improved electricity interconnection could save up to £1billion pa or around £11 per household. As we introduce increasing intermittency in our generation mix the need for increased interconnection will be greater and will enhance competition in the wholesale electricity market.

At the end of last year DECC published its interconnection strategy but we would be keen if your work were to indicate what benefits there might be for competition and for consumers from further steps towards completion of a Single European Energy market of which interconnection could play an important part. I also would like you to examine whether there would be any merit in further gas pipeline interconnection with Europe.

Whilst our gas prices including tax relative to rest of Europe are relatively low I think there is some evidence that this is not the case once adjustments are made for tax and distribution costs. Would further gas pipeline interconnection help to drive down gas wholesale costs?

New business models

The most effective way to reduce consumer bills is to improve the energy efficiency of our homes. This is also one of the most effective ways to reduce our carbon emissions. However one of the longstanding concerns about the current energy supply market is that the current Big 6 energy suppliers still see their role as selling gas and electricity rather than having a different business model where the value proposition is to save households energy.

This has been seen most recently where the Big 6 have been slow to embrace the Green Deal, and in a number of cases the Energy Company Obligation, As part of Electricity Market Reform we are seeking to promote Electricity Demand Reduction (EDR) and this year will be launching a number of EDR pilots as part of these efforts. I am particularly keen therefore that the market is encouraged to develop in such a way as to promote energy efficiency.

My officials would be happy to discuss any of these points further if you wish as you develop your analysis and thoughts.

Ed Davey

Comment

This was a beautifully crafted letter in the way in which the Department of Energy paid lip service to 'regulatory independence' whilst in truth issuing what amounts to orders to the two regulators - albeit orders that they could legally ignore. But it was certainly yet more evidence of the Department assuming responsibility for regulatory decisions in the energy sector. And it again nicely diverted attention away from the fact that a very high proportion of recent and future energy price rises were the direct result of government climate change policies, for which the LibDems - Ed Davey's party - had been the principal cheerleaders within the coalition.

The very good thing about the letter - confirmed by Ed Davey when speaking on the Today programme on 10 February - was the heavy hint that he would be pleased if Ofgem were to refer the energy market to the CMA for a market investigation - and about time too! The CMA was the only body that has the power to establish all the necessary facts and could, after completing a market investigation, actually impose quite dramatic remedies, including breaking up the larger companies.

The less good thing was the emphasis on profit percentages being evidence of a problem with market structure - when they can be evidence of efficiency (British Gas, being a very large company, will benefit from economies of scale) or of insufficient switching - which is a problem but maybe not a result of British Gas being too big. But a full CMA market investigation would certainly allow these issues to be explored in proper depth.

Ofgem's Decision

Then - what a surprise! - Ofgem announced in March 2014 that, subject to final consultation, they intended to refer the market to the CMA. Here are some extracts from their press notice, in which I think they expressed concern about tacit coordination/collusion for the very first time.

The CMA has powers, not available to Ofgem, to address any structural barriers that would undermine competition. Now consumers are protected by our simpler, clearer and fairer reforms, we think a market investigation is in their long-term interests.

The headline findings of [our competition] assessment are:

Weak customer response: Switching has fallen over recent years. There was a brief spike in late 2013 but no indication of a permanent increase. Consumer trust has also fallen significantly: 43% of consumers did not trust energy suppliers to be open and transparent in their dealings with them in 2013, compared to 39% in the previous year. This low level of consumer engagement is not consistent with a competitive market.

Continued evidence of incumbency advantages: The market shares of the six larger suppliers in gas and electricity have not changed significantly over time and they all have a high proportion of customers who never, or rarely engage in the market. They are able to charge higher prices to these "sticky" customers while making cheaper deals available to more active customers.

Possible tacit co-ordination: The assessment has not found evidence of explicit collusion between suppliers. However, there is evidence of possible tacit coordination reflected in the timing and size of price announcements and new evidence that prices rise faster when costs rise than they reduce when costs fall. Although tacit coordination is not a breach competition law, it reduces competition and worsens outcomes for consumers.

Vertical integration and barriers to entry and expansion: The six larger suppliers all own energy infrastructure such as power stations and supply businesses. This makes it difficult for new entrants (who don’t own such assets) to compete against them, particularly in the electricity market. Ofgem’s reforms to open up the wholesale power market aim to tackle this. However there are wider issues with vertical integration which need a close review. While the market share of independent suppliers has grown in the last year to 5 per cent there are barriers to entry and expansion which may prevent them from posing a disruptive competitive threat.

Profitability: The average profits for the six larger suppliers for supply and generation have increased from £3bn in 2009 to £3.7bn in 2012. The Assessment does not come to a conclusion as to what is the appropriate profit margin for the industry but notes the recent increases and questions the suppliers’ contentions that 5% is a fair margin. While the evidence on profitability is not conclusive, the rise over the last few years allied to no clear evidence of increased efficiency is indicative of a possible lack of effective competition.

Comment

Ofgem had wasted 10 years before finally deciding that a market investigation would be a good thing, but it is greatly to the credit of their new Chair and Chief Executive that they were willing to reverse Ofgem's policy.

But the politicisation of this regulatory area was underlined by the Energy Secretary's appearance on the Today Programme and in Parliament on 27 March when he appeared to take personal credit for what was supposed to be a decision - yet to be finalised - taken by an independent regulator.

And Labour's Shadow Energy spokesperson asserted, in the same programme, that Labour both welcomed the CMA investigation and would also, if elected, press on with the 10 point energy plan announced at the 2013 Party Conference - including the separation of generation and supply, and the introduction of a new electricity open pool. These are two quite incompatible ways of responding to the problems of the energy market.

Catherine Waddams' blog, a day or two later, added further perceptive comment (some text deleted, and emphasis added):

The decision to refer the energy market to the new CMA will be welcomed by many but will also have costs. On the positive side, the opportunity for a thorough review of the market enables analysis without immediate political pressure, either directly on the market or on the regulator. It is important to restore public confidence in the market, either by giving it a clean bill of health, or identifying any problems and remedying them.

But such market investigations are costly. … The inquiry will take eighteen months to reach a conclusion, and this period might be extended through appeals against potential remedies, such as vertical separation of companies, during which investors might be reluctant to commit funds. But the current arrangement is also fraught with uncertainty, and investors might be more comfortable with a well-structured competition inquiry than with intermittent and apparently random interventions from politicians. As one of the first market inquiries for the new CMA, we would hope for a period of stability and acceptance at the end of the process, so that the sector can be left to develop with more confidence from both decision makers and the general public.

These benefits will only be maximised if politicians stop using the market as a political football by calling for structural changes or price freezes – the object of an inquiry is first to establish whether the market really is ‘broken’ i.e. whether there is a feature or features which have an ‘Adverse Effect on Competition’ (an AEC). Only if the CMA does find such an effect will it go on to suggest appropriate remedies, which will depend, of course, on the nature of any AEC which is established.

Of course politicians intervene in this market because energy is essential both for industry and commerce and, more particularly, to households. … It is not surprising that politicians find voters are responsive to their calls for action. The danger is the familiar fallacy of ‘something must be done. ‘This’ is something. Therefore ‘this’ must be done.’

As in any market it is all too easy to make mistakes. The regulator, anxious to alleviate concerns that the ‘Big Six’ energy suppliers were discriminating against the households who had never switched supplier, imposed non-discrimination clauses which contributed to a reduction in competition, a decrease in the size of savings which could be made from changing supplier and a consequent dramatic fall in switching, which remains very low despite the inroads of new entrants. Stephen Littlechild has estimated that this intervention added up to £3billion per year to household bills in 2013, around an additional £135 per year for a dual fuel household. Some of the regulator’s more recent changes to simplify tariffs will have similar effects on competition and price levels. Against this background there are obvious benefits of an in depth analysis of the market from a new perspective. ...

Features of the market which have an Adverse Effect on Competition might be intrinsic to the sector, or a result of earlier developments or regulatory intervention, and the Authority will need to decide how far these are reversible. The reference is important to the competitiveness of the UK and to the well-being of every household, as they face rising underlying energy costs in the coming years. These rising trends make it all the more important that the market works as well as it can do, and that consumers, companies, politicians and potential investors have well-placed confidence in its operation. The CMA has an important and high profile challenge as one of its earliest inquiries.

SSE's Price Freeze

The political waters had also been muddied, a day or two before Ofgem's announcement, by energy company SSE announcing its own 20 month price freeze, thus apparently taking the wind out of the sails of those who had criticised Labour's proposed 20 month freeze. Three points can be made their defence, however:

- It is easier and safer for a company to announce a freeze beginning immediately, for they will have some idea of how their costs are likely to move, and they will have hedged the cost of some of their purchases. It is considerably more dangerous to announce, in September 2013, a price freeze that will not begin until May 2015.

- It is in principle undesirable for politicians to intervene so dramatically in a market, for companies should be left free to make their own pricing decisions. (This is not, however, an argument which appeals to most consumers who are faced with rocketing gas and electricity prices.)

- As Ian King pointed out in The Times:- 'it turns out energy price freezes of the kind proposed by Ed Miliband are possible ... provided you are prepared to cut 500 jobs and to chop capital expenditure by at least £300 million a a year in each of the next three years. This, in the case of SSE, means shelving various offshore wind, biomass and wave power developments.' This may not have been an intended consequence of Labour's policy.

Energy Prices Then Fall

The end of 2014 and the first few weeks of 2015 saw a very sharp reduction in the wholesale price of oil and gas. Oil had peaked at over $120 per barrel, but fell to below $60. As ever, UK gas and electricity prices fell much more slowly, partly because they included many costs other than the cost of raw energy, partly because the energy companies had previously committed to buying energy at much higher prices, and (perhaps) partly because of faults in the market, yet to be confirmed by the CMA. It was also distinctly possible that the companies were reluctant to reduce prices lest an incoming Labour Government - maybe only weeks away - proceeded to implement its threat to freeze prices.

Both the main political parties felt they had to announce something, responding to the delay in reducing energy prices, even though they were awaiting the result of the CMA investigation. The Chancellor asked his officials to begin their own investigation - much less well resourced than the CMA's parallel inquiry. And Labour pressed for Ofgem to be given emergency powers to force the companies to reduce their prices. I have little doubt that Ofgem would very much not want to have these powers as they would have no reliable analysis on which to base a decision, and they would certainly not want to distort the market - especially in advance of the CMA's decision - whatever the party political attractions in doing so.

CMA Investigation

There is a wealth of illuminating evidence on the CMA's website. But the note of the hearing with Centre for Competition Policy is probably a good place to start.

The CMA summarised their developing thinking in February 2015. The main points of interest were as follows – but it must be stressed that these were subject to considerable further investigation and consultation.

- It is too soon to begin to draw conclusions about competition in the retail market, but the six large energy firms do appear to have market power – i.e. they are to some extent immune from pressure to compete with each other. This may have led to their generating excessive profits

- Between 2012 and 2014, 95% of dual fuel customers could have saved money by switching suppliers. The average saving, depending on the supplier, would have been between £158 and £234pa.

- Some of these customers did switch, but those that did not were typically elderly, in social accommodation, poorly educated, and/or on lower incomes.

- The recent Retail Market Review changes (inc. forcing suppliers to have only four core tariffs) may have tended to increase prices, not reduce them.

- The absence of locational pricing of electricity may be a problem. Suppliers could compete more effectively if they could offer lower prices to new customers outside the areas where, for historical reasons, they already have a strong customer base. On the other hand, it would make more sense if electricity cost more if it were used a long way from where it is generated, because some of it is lost as it is transmitted along long wires. (But note that this would not be good for green generation, which usually takes place a long way from big cities.)

- Vertical integration (e.g. the same companies owning both the electricity generators and the companies that supply consumers) does not look as though it causes competition problems.

The CMA's subsequent Provisional Findings were disappointing - and that is not a criticism of the CMA, just an acknowledgment of the fact that the CMA, like Ofgem, has failed to find an easy and acceptable way to tackle the problems of the energy market.

First, it gave up on trying to prove that tacit coordination (aka tacit collusion) had taken place. This is not to say that it has not taken place - see the charts here - but there was insufficient evidence to to draw a conclusion which could be safely challenged in court, so a long and expensive fight, which might well have been unsuccessful, was tactically far from sensible.

Second, to no-one's great surprise, the CMA provisionally found that 'competition in the wholesale gas and electricity generation markets works well, and the presence of vertically integrated firms does not have a detrimental impact on competition. It has also found that there is no strong case for returning to the old ‘pool’ system for the wholesale electricity market.'

So that forced the CMA to re-examine all the familiar issues to do with customers' reluctance to switch suppliers. It noted that:

Electricity prices have risen by around 75% and gas prices by around 125% in the last 10 years.

The average household currently spends about £1,200 on energy each year. For the poorest 10% of households, energy bills now account for about 10% of total expenditure. However, widespread consumer disengagement is impeding the proper functioning of the market. An extensive survey of 7,000 people in Great Britain found that over 34% of respondents had never considered switching provider.

As a result ... dual fuel customers could save an average of £160 a year by switching to a cheaper deal. About 70% of customers are currently on the ‘default’ standard variable tariff (SVT) despite the presence of generally cheaper fixed-rate deals. Lack of awareness of what deals are available, confusing and inaccurate bills and the real and perceived difficulties of changing suppliers all deter switching – and the higher price levels reflect that suppliers can charge higher prices to these disengaged customers.

Regulatory interventions designed to simplify prices, such as the ‘four-tariff rule’, are not having the desired effect of increasing engagement, and have limited discounting and reduced competition.

Put another way, the CMA calculated that domestic prices are c.5% (c£1.2bn) too high, and small firms are paying around 14% too much (£0.5bn) for their energy.

But what was to be done about it? The CMA consulted on a complex package aimed at increasing switching, backed up by a hopefully temporary price-controlled default tariff. The Prime Minister reacted by saying that he didn't like the idea, before next day saying that he would consider a temporary price cap, and then finally realising that he has no power to overrule the CMA who can impose a price cap whatever he says.

But the Centre for Competition Policy was lukewarm, noting that 'there needs to be headroom for such a tariff, to encourage companies to continue to offer good deals to those who are active; the protection therefore needs inevitably to be somewhat above the best deal on the market, so protection is, in a sense, partial. But there is a real danger that it may disengage even more consumers, who will feel that the authorities are looking after them, and so there is even less reason for them to follow what can seem a boring and tedious road to switching suppliers. It is a bit like having half an umbrella – if consumers think it will keep them dry, they may not use adequate precaution against the rain, and take a financial shower as a consequence.'

Dieter Helm was much more critical, and his views are worth reading in full. He notes the 'deep and fundamental tension between an outright competitive solution and a regulated solution'. He goes on to point out that there are costs (such as the cost of time) as well as benefits in switching and it is perhaps not surprising or in any sense wrong that many customers do not choose to switch. 'Why would customers want to spend their evenings comparing alternative electricity and gas supplies, when they have many other pressures on their time? Rational customers live in time-pressured households. They make lots of "mistakes" because of these pressures. They have other priorities ... the costs of "complications' if it goes wrong are likely to involve very considerable hassle ... There is no convincing evidence that [large scale switching will ever work]'.

(There are echoes of behavioural economics in his analysis. And click here for a further discussion of the extent to which it makes sense to offer consumer protection.)

George Yarrow then weighed in with further criticism's of the CMA's approach, noting, for instance, that "a wide range of markets are characterised by the existence of sub-sets of consumers who are significantly less responsive ... than are other consumers" but that doesn't mean that there exists an Adverse Effect on Competition that must be identified before the CMA can intervene. Professor Yarrow's full submission, including entertaining references to Healey's Law (When in a hole, stop digging) and the pork pie factory of economic life is here.

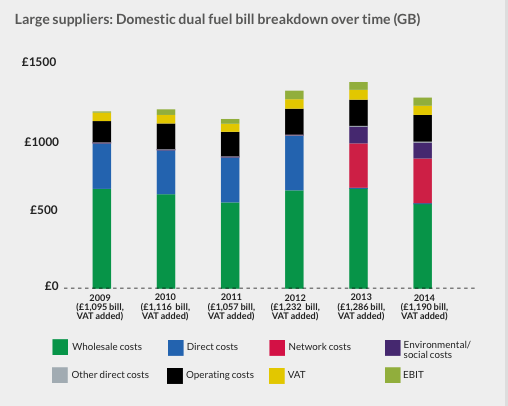

Ofgem published the following chart in October 2015. Note the price fall in 2014. The prior year figures look a little different to those on my 'overview' web-page, possibly because the company sample is different, but the broad trend is the same.

The CMA's final conclusions are summarised in the following web page which reports developments from 2016 onwards.