Government intervention in energy markets has gone full circle over the last forty years. Back in the 1970s, when it owned the gas and electricity industries, government not only had a hand in all significant decisions, but it also tasked those industries with a number of incompatible objectives, and especially social objectives. It then privatised the industries in the 1980s and established independent regulators (in due course consolidated into Ofgem) who focussed on introducing effective competition and (if necessary) controlling prices. But government intervention began to grow back, beginning around 2003, and is now substantial.

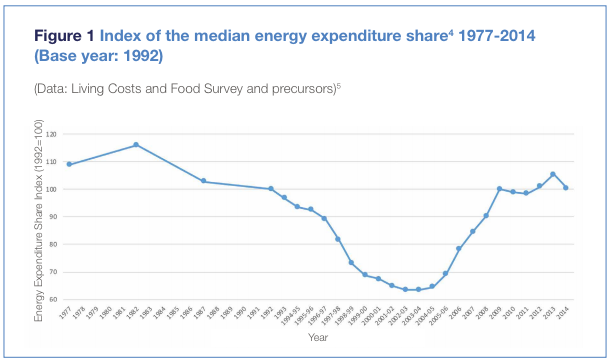

This chart shows very clearly that - whatever its other virtues, for instance its willingness to tackle climate change - Government interference in the energy market seems inevitably to lead to higher prices. (See more detail here and also Note 2 below.)

The structure of the post-1980s privatised industry has several tiers.

Generation and Storage

1. First of all, one set of wholesale companies (including electricity generators and gas storage companies) compete to supply gas to, and generate electricity for, the suppliers - see '4' below.

Transport

2. The energy is then transmitted around the country by transmission companies such as National Grid.

3. It is then distributed to consumers by 14 distribution network companies such as Western Power Distribution which owns and operates the power grid in South Wales, the Midlands and the South West of England. Each one is a regional monopoly whose prices are set by Ofgem.

Supply

4. Customers deal only with suppliers who buy energy on customers' behalf, reimburse the transmission and distribution companies for their services, and issue bills etc.

The theory underlying this structure looks sensible. The original big idea was to get the benefit of generation etc. competition through to customers. In other words, your and my supplier would seek out the cheapest gas and electricity on our behalf, and if they failed then we would switch to another supplier. The wholesale companies (1) would compete with each other, as would the customer-facing suppliers (4). And Ofgem would control the prices of the transition and distribution natural monopolies (2 & 3). In practice, however:

- the market suffers from distortions introduced by various of the Big Six energy companies (British Gas, EDF, E.ON, npower, Scottish Power and SSE) owning both generators and suppliers (1 & 4) ..

- .. as well by the prevalence of tacit coordination whilst ..

- .. the widespread 2013/14 Christmas/New Year storms, which led to much loss of power in rural areas, brought home to customers that their suppliers were not directly responsible for actually getting the electricity to their homes. Calling the suppliers' emergency numbers therefore had little effect as the suppliers could do no more than pass on the information and forecasts that they had received from the transmission and distribution companies.

There were nevertheless around 20 years in which government did its best to leave energy policy to Ofgem and the market. This was initially pretty successful. A good deal of competition, if not fully effective competition, developed in electricity generation and in gas/electricity supply to homes and businesses, thus allowing price controls to be removed from these elements of the supply chain. Transmission and distribution remained price controlled, because the pipes and wires created natural monopolies. As a result, operating costs fell by over 50% in real terms following privatisation, and UK gas/electricity prices became lower than prices charged in most other comparable countries. However, a number of factors (including concerns about climate change, concerns about nuclear generation, increasing gas import dependency, and the closure of ageing power stations - all of which led to increasing retail gas/electricity prices) meant that energy policy inevitably became much more political, and control of energy policy slowly drifted away from Ofgem and back to the Government.

The process probably began in 2003 when a significant power outage in London alarmed both the industry and the Government and led to increased spend on distribution networks. But concerns about climate change, and the apparently inexorable rise in the price of fossil fuels, led the Government of the day to demand increased emphasis on de-carbonisation and the generation of energy from renewable sources, thus creating lots of policy conflicts. From 2004, therefore, Ofgem was no longer allowed to concentrate on economic regulation but instead had to take note of environmental and social guidance which required it to seek

(a) carbon reduction,

(b) reliability and security of supply,

(c) competition, and

(d) adequate and affordable heating.

But Ofgem was offered no guidance on how to prioritise these conflicting objectives. Indeed:- 'The Government has not sought to rank the four objectives set out in the White Paper. It is the Government's view that these objectives can be achieved together and the Government has put in place policies designed to achieve this.'

The next significant development was when the Department of Energy, which had been absorbed in the Business Department in 1992, was resurrected as the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) in 2008. Ofgem continued to remain much more independent than its counterparts in most other EU countries. But it became increasingly unpopular with the then Labour Government which was frustrated by Ofgem's refusal to refer the energy market to the Competition Commission.

A New Government

Energy policy had risen to pretty near the top of the political agenda by the time of the 2010 General Election. This was because politicians found it very difficult to establish a satisfactory combination of policies which (a) tackled climate change, and (b) encouraged investment in new generating and distribution capacity without also (c) increasing taxes or energy prices to an unacceptable extent.

Pre-2010 Labour Party politicians had hoped that Ofgem would help them by referring the energy market for a full (and likely two year) investigation by the Competition Commission (CC), but it had not done so. However, after the 2010 General Election, when it looked as though a reference might be made, Conservative junior minister Charles Hendry intervened so as to delay a reference. He clearly interfered in Ofgem's independent decision making when, in February 2011, he told The Times that "suppliers might be too important to future energy security to be exposed to the full rigours of a competition investigation ... We have to be aware that these are the same companies which we are asking to help find much of the £200 billion of investment in the energy market that this country needs ... This is not an issue just about prices". Commentators were not impressed. Andrew Ellison said that the 'cowardy custard' Minister ought to 'show more backbone ... we have gone from a sofa style of government to a hide-behind-the-sofa style of government ... Besides, it is hard to imagine that energy suppliers would refuse to invest in one of the largest economies in the world simply because they are forced to charge a fair price'. Mr Hendry was sacked in Prime Minister David Cameron's first reshuffle in September 2012. But there was still no reference to the CC.

Later in 2010, Ofgem's rather good Project Discovery Report was said to have appalled the new Coalition Government who did not wish the public to be told about the regulator's concerns about insufficient generation capacity. But the Government was forced to conclude that, if it did not act by investing in gas-fired power station, then lights would start going out (including in poor people's homes) well before (climate change driven) water started lapping at voters' doors! However, rightly or wrongly, the Government in general, and DECC and Infrastructure UK in particular, did not trust Ofgem to drive through the necessary energy price rises necessary to ensure the required investment in their sectors. The obvious conclusion, in the Government's view, was to take firm control of energy policy. They accordingly established an internal Electricity Market Reform Project and an Electricity System Programme - both the sorts of jobs that would in earlier times have been carried out by Ofgem. (Contrast Ofgem's earlier responsibility for developing NETA, the New Electricity Trading Arrangements introduced in 2001.)

(There is a note here about concerns that there will be insufficient electricity generation capacity in forthcoming winters.)

The policy of the new coalition government accordingly became driven by four factors:

- First, it had by then become clear that there would need to be huge private sector participation in the investment in UK infrastructure, including energy infrastructure, over the period 2011-2015. The government had accordingly created Infrastructure UK within HM Treasury to make sure that this private sector investment took place. But energy and other customers would eventually have to fund all this investment via their bills.

- Despite earlier concerns about the rising price of fossil fuel, gas now appeared to be becoming more plentiful and less expensive. The US was rapidly exploiting its huge and inexpensive shale gas reserves - and there was the possibility that we too might discover significant reserves. This appeared to make it much more expensive (and hence less attractive) to decarbonise as fast as environmentalists (and the Lib-Dems within the Coalition) would wish.

- Gas is much less carbon-intensive than coal. Coal is pretty much pure carbon and so produces only CO2 when burnt. Gas is a hydrocarbon and contains a lot of hydrogen, and so produces relatively less CO2 and a lot more harmless H2O (water) when it is burnt. It is therefore less damaging to the environment

- But the government was also very worried about security of supply, knowing that old coal-fired power stations were to be phased out well before any new nuclear plant was phased in.

The Government's 'dash for gas' (and nuclear) is described in more detail here.

A number of announcements, in December 2010, led The Times to headline its report 'Energy all-change means bigger household bills for the next 20 years'. One element of this package was Ofgem's abandonment of the familiar RPI-X price control formula, which exerts strong downward pressure on industry costs. Instead, the regulator was switching to RIIO, in which Revenues are determined by levels of Innovation, by Incentives and by the Outputs they deliver. Costs and efficiency (and hence lower prices) thus became much lower priorities, whilst investment, including in green technologies and a 'smart' grid are encouraged. Speaking some years later, Ofgem Chair David Gray said that the main features of the new approach were:

- first, the requirement for companies to engage with stakeholders and get some real input on what consumers and users of the network want.

- linked to this, a clear statement of the outputs that we and other stakeholders can expect on the basis of the price control allowances.

- the 8 year review period which was intended to encourage longer term thinking but should also have the valuable effect of providing a more stable business flow for the supply chain

- the increasing use of mechanisms to deal with uncertainty - re-openers and volume drivers to deal with the more unpredictable items and the mid-period review to deal with any changes to the required outputs.

- the use of totex allowances – rather than capex and opex separately – trying to remove any unintended bias towards capital solutions.

- and, finally, measures to encourage innovation which could potentially provide as much as £1 billion for research and trials during the first round of RIIO price controls.

He also felt that the new approach had been found to work well, noting in particular that the resultant price controls had been upheld on appeal by the CMA - at least in seven and a half of the nine main grounds of appeal.

Notes

1. The gas industry was originally privatised as a vertically integrated 25 year monopoly. There were, after some time, then a series of investigations by the Office of Fair Trading and the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (now the CMA). At least one of these was welcomed by British Gas itself which then decided to separate itself into two companies - upstream transport and storage; and downstream supply to the customer.

2. Secretary of State for Energy, Tony Benn offered to impose gas price increases on customers so as to help the government to meet tough IMF borrowing targets. An incidental benefit of this (in Mr Benn's mind) was that it would help his beloved coal industry.

3. There was a famous episode in the early days of electricity regulation when the regulator, Stephen Littlechild, was forced to re-open a price control after only around a year after setting it. In brief:

- He sent his opening (and deliberately tough) proposals to the 12 supply companies expecting them to argue him down, so to speak. His P0 (immediate price reduction) was 20% to be followed by Xs (annual price cuts reflecting expected efficiency savings) of 4% pa.

- One of the companies leaked his proposals which led to sharp falls in all the companies' share prices.

- He eventually imposed P0s in the range 11-17% with Xs of 2.

- Whereupon the share prices rose very quickly - and stayed high, leading to much public and political criticism of the decision.

- A subsequent MMC decision on another case gave him the excuse he needed to re-open the price control, settling on a P0 of around 13% and Xs of 3.

4. For more detail, I recommend Catherine Waddams' 2018 history and analysis of energy price controls.