Smart Meters

2016 was the year in which the major roll-out of 53 million smart meters was intended to begin, only 4% having been installed previously. The cost was estimated to be £11,000 million to be met by consumers via a levy on their energy bills, which would hopefully be lower as a result of better information management by both the energy suppliers and their now-more-savvy customers. It would be possible, for instance, to change supplier within 24 hours. Critics suggested, however, that the technological approach was already out-dated, that the savings would not justify the cost, and that the cost was anyway much higher than necessary.

It emerged that there was a particular problem in that the first generation of smart meters were specific to the energy supplier and either didn't work or had to be replaced if the customer switched supplier. There was also more generalised resistance to their installation as individual householders couldn't face the hassle of having an engineer call to install the new meter. It was accordingly reported in August 2017 that (a) there was a shortage of smart meter fitters because the companies had to recruit to demonstrate that they had the capacity to complete the installations by 2020, and yet (b) many of the fitters were partly idle because of customers' lack of interest.

Effective Competition

The market share of the Big 6 had by now reportedly fallen to 85%, from 99% in 2012.

Hinkley Point

Early 2016 saw further delay in the investment in nuclear power. Click here for further detail.

Ofgem - a Soft Regulator?

There was an interesting little spat early in 2016 when critics claimed that Ofgem had been too slow to tackle mis-selling and poor service through the the industry. The (relatively new) Chief Exec responded by noting that the regulator had imposed more than £200 million in penalties since 2010. But as Michael Cullen then pointed out, that averaged "less than £1 per year per inhabitant of the UK. The leaders of the power industry must be quaking in their boots". (That's British sarcasm, folks.)

The CMA Report

The Competition and Markets Authority published its final report in June 2016, grappling yet again with the tension between competition and protection. Competition is of course the best way to ensure lowest average prices, and highest average service quality, but it carries no guarantees about which particular customers win and lose as a result of the process. The CMA noted that 70% of customers of the Big 6 energy firms were on standard variable tariffs (SVTs) and they could on average save £300pa if they were to shop around for a better deal. But:

- the CMA had never taken very seriously the idea that the larger companies should be broken up,

- nor that there should be an attack on tacit coordination.

- The authority also abandoned the idea of a temporary price cap for SVTs because this would have had the perverse consequence of removing the incentive for customers to shop around and so reduce the pressure on energy suppliers to reduce their prices.

- They also decided that Ofgem's 'maximum of four tariffs' rule should be abandoned, for the same reason.

- And the CMA did not require the introduction of 'simplified energy bills' - that is bills with simple petrol station-style prices and no standing charges. These would have greatly encouraged competition, although they would be less cost-reflective given the fixed cost of providing an energy supply to the door.

Their principal recommendation was that there should be a secure database of 'disengaged customers' who could be targeted by energy companies who could offer them lower prices, although sceptics such as Catherine Waddams noted that "People who aren't switching now are unlikely to start because they receive more [junk mail]. Most won't even bother to open the envelope let alone go further."

The CMA also imposed a temporary price cap (often referred to as a transitional price control, to be abolished on the introduction of smart meters) to help those using prepayment meters. These customers are often quite poor and yet pay more for their energy than those who pay in arrears. The cap was introduced in April 2017 and lowered, typically by £19pa, from October 2017.

Follow this link for a further discussion of switching and effective competition.

As an aside, German RWE-owned Npower announced around the same time that it planned to cut 2,400 jobs – a fifth of its workforce – to reduce costs after losing customers, offering bad customer service and suffering poor financial results. So competition was working to some extent, at least.

One potentially significant CMA recommendation was the introduction of locational pricing for transmission losses - the energy that is lost when electricity is transported from one part of the country to another. This would encourage generation nearer to customers - potentially disadvantaging 'green' energy that is generated on distant hillsides or out at sea.

The investigation was estimated to have cost the industry (or its customers?) £75 million, and to have cost the CMA (i.e. the taxpayer) £5 million.

Not everyone was impressed. One CMA group member, Martin Cave, dissented from part of the conclusions and Dieter Helm reckoned that the companies had defeated the CMA 5-Nil. His paper is here. Others joined him in being sceptical that the arrival of smart meters (supposedly in every home by 2020) would be transformational in increasing customer engagement. Others thought that the CMA could have been more innovative in encouraging modern price comparison technology, believing that tech-savvy customers would put the energy firms under much more competitive pressure once the necessary online and mobile tools were available, as had been recommended by a separate CMA group looking at retail banking. But the CMA sledgehammer seemed to quieten concern about energy prices, for a while at least.

The CMA's own summary of its conclusions is in this separate note. And, perhaps stung by the criticisms, a pretty good defence of their recommendations was made a year later in a speech by the Inquiry Chair Roger Witcomb.

Interesting Behavioural Science Report

Robert Hahn and Robert Metcalfe published an interesting paper in 2016 - The Impact of Behavioral Science Experiments on Energy Policy They noted that one of the most exciting areas of current research was the use of experiments to better understand how various behavioral interventions change the energy consumption decisions of consumers and businesses. 'Many policy makers face severe constraints, and are unable to alter markets, regulation, or taxes, so that the price of energy reflects its full social cost. Understanding and changing the pattern of energy consumption is critical for a variety of reasons, including meeting the challenge of climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.' They then identified four general insights from the literature.

- First, the “law of demand” is typically satisfied in experimental settings, but responsiveness to energy price changes can vary dramatically in different contexts.

- Second, information provision can help promote reductions in energy use, but it does not always work.

- Third, the use of social norms can change energy use.

- Finally, the economic welfare impacts of behavioral interventions aimed at promoting either energy conservation or energy efficiency are not well understood, but initial research suggests that some people want nudges and some do not.

The Levy Control Framework

A National Audit Office report in October 2016 made uncomfortable reading for the government and its civil servants (emphasis added):-

'The Levy Control Framework, established by the former Department of Energy & Climate Change (the Department) and HM Treasury, set a cap for the forecast costs of certain policies funded through levies on energy companies and ultimately paid for by consumers. Since November 2012, the Framework has covered three schemes to support investment in low-carbon energy generation: the Renewables Obligation, Feed-in Tariffs and Contracts for Difference. It sets annual caps on costs for each year to 2020-21, with a cap of £7.6 billion in 2020-21 (in 2011-12 prices).

According to the latest forecast, the schemes are expected to exceed the cap and cost £8.7 billion in 2020-21. This is equivalent to £110 (around 11%) on the typical household dual fuel energy bill in 2020, £17 more than if the schemes stayed within the cap. ...

According to the NAO, the government failed to fully consider the uncertainty around its central forecasts and define its appetite for the risks associated with that uncertainty. If the Department and HM Treasury had asked more explicitly ‘what if our forecasts or key assumptions are wrong?’, this might have prompted more robust design and monitoring of the Framework, and reduced the likelihood of significantly exceeding the Framework’s budgetary cap .... government needs to do more to develop a sufficiently coherent, transparent and long-term approach to controlling and communicating the costs of its consumer-funded policies. This should include providing an updated report on the impact of its energy policies on bills, as the relationship between Framework costs and the affordability of energy bills is not straightforward.'

Prices Fall then Rise Again

A number of factors, including the ready availability of shale gas, and Saudi determination to maintain market share, led to sharp falls in wholesale energy prices in the earlier months of 2016, but prices begin to rise again - though not to their previous high levels - towards the end of the year. This had three interesting consequences.

The first was that the lower prices made nuclear power in general, and the Hinkley Point deal in particular, look very expensive.

The second was that the rebounding (i.e. rising) prices made it harder for the smaller energy companies - and particularly those that had been set up by municipal authorities - to compete with the Big 6. This was because the larger companies buy much of their gas and electricity months or years in advance so as to secure their supplies. This is one reason why they are slow to reduce their prices when wholesale prices fall - so they can then be easily undercut by smaller competitors. When prices rise, however, the smaller companies need to start buying energy in advance if they are not to lose out - but they may not have the financial muscle to do so.

The third was that there was renewed pressure to cap energy prices, particularly the standard variable tariff. The 2017 Conservative Manifesto contained this commitment:

We will pay immediate attention to the retail energy market. Customers trust established brands and mistakenly assume their loyalty is rewarded. Energy suppliers have long operated a two-tier market, where those constantly checking for the best deal can do well but others are punished for inactivity with higher prices. Those hit worst are households with lower incomes, people with lower qualifications, people who rent their home and the elderly. A Conservative government … will introduce a safeguard tariff cap that will extend the price protection currently in place for some vulnerable customers to more customers on the poorest value tariffs. We will maintain the competitive element of the retail energy market by supporting initiatives to make the switching process easier and more reliable, but the safeguard tariff cap will protect customers who do not switch against abusive price increases.

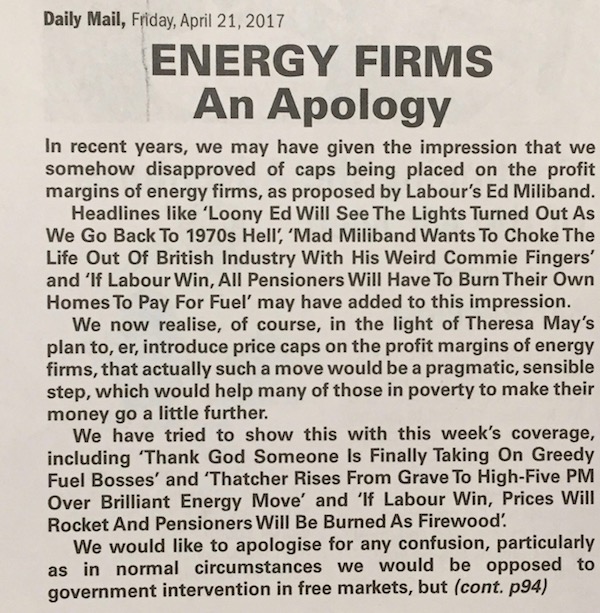

This was met by a fair amount of derision, not least from those who remembered the Tory rubbishing of Ed Miliband's similar commitment before the 2015 election. Roger Witcomb, the Chair of the CMA Inquiry (see above) said that it was "entirely understandable that politicians will wish to continue to seek the holy grail of a price control that does not undermine competition" but the CMA had been unable to find it. A price cap that effectively tackled the problem of overpaying would need to be set close to that which would be seen in a competitive market. Prices would therefore converge at that level, customers would "figure that they have no need to shop around" and suppliers would realise that there was now no incentive to compete by innovating, identifying efficiencies and seeking low-cost supplies.

This was met by a fair amount of derision, not least from those who remembered the Tory rubbishing of Ed Miliband's similar commitment before the 2015 election. Roger Witcomb, the Chair of the CMA Inquiry (see above) said that it was "entirely understandable that politicians will wish to continue to seek the holy grail of a price control that does not undermine competition" but the CMA had been unable to find it. A price cap that effectively tackled the problem of overpaying would need to be set close to that which would be seen in a competitive market. Prices would therefore converge at that level, customers would "figure that they have no need to shop around" and suppliers would realise that there was now no incentive to compete by innovating, identifying efficiencies and seeking low-cost supplies.

Other critics pointed out that

- the Big Six made an operating profit of less than £1 a a week per dual fuel customer, so a cap which had a significant effect would inevitably trigger significant increases for those currently on cheaper tariffs, and

- four of the Big Six were foreign owned and would be deterred from investing further in the UK, especially following Brexit.

More generally, journalists wondered (somewhat tongue in cheek) whether Ministers would in due course attack variable rate mortgages and/or supermarkets who sold the same food at different prices to their competitors - or sometimes at different prices even within the same store.

But the right wing press were more supportive. Private Eye's reaction is opposite.

Developments from 2017 are summarised here.