The regulation of risks to health and safety is a particularly tricky policy area. There are constant complaints that we are paying far too much attention to health and safety, and producing dull young adults who are risk- and exercise-averse. However ...

The regulation of risks to health and safety is a particularly tricky policy area. There are constant complaints that we are paying far too much attention to health and safety, and producing dull young adults who are risk- and exercise-averse. However ...

- there are now less than 2,000 deaths on our roads every year, compared with around 8,000 in the 1960s, and

- we have cut child deaths as a result of preventable accidents from 1,100 in 1979 to less than 200 in 2011.

There aren't many parents who would turn back these particular clocks, especially as parents are having fewer children, and seem seem to be much more invested in their offspring, both for the children's sake and as extensions of the parents' identity. Parental fear that one silly incident might lose it all is inevitably overwhelming.

On the other hand - the UK has invested heavily in automatic train protection (ATP) where every £5 million was said to save one life - but the same expenditure could save many more lives on the roads. How can this make sense? A wonderfully entertaining and thought-provoking introduction to the perception of risk, risk compensation and risk management, may be found in Professor John Adams' writing, beginning with his 1998 lecture Risk in a Hyper-Mobile World.

We are generally comfortable with risks that we take every day, but new ones, or dramatic ones, worry us. More detail may be found in this note about how Government should respond to concerns about risks to health and safety.

We are generally comfortable with risks that we take every day, but new ones, or dramatic ones, worry us. More detail may be found in this note about how Government should respond to concerns about risks to health and safety.

But problems arise when politicians and bureaucrats over-react, perhaps fearful of targeted criticism and failing to see the bigger picture. Legislators, regulators, vehicle designers and road engineers appear, for instance, to have achieved huge success in reducing fatalities per motor vehicle kilometres, but did they really? How much of this was instead due to changes in attitude, and to deterring pedestrian and cycle traffic? This Cycling and Safety presentation raises some interesting questions. And it is interesting to think about how we are responding to the new risks associated with the development of autonomous vehicles.

And was it really necessary to require 11.3 million people to pass criminal records checks before working with children and vulnerable adults? Leaving aside the mind-boggling expense and bureaucracy required to perform this feat, its effect might well be perverse. A CRB check might come to be seen as an insurance policy; behaviour that might previously have aroused suspicion might now be less likely to be questioned because some superior authority has certified the suspect as 'safe'.

Key documents in this area include a Review of Risk Case Studies, and the October 2006 report by the Better Regulation Commission: Risk, Responsibility, Regulation: Whose Risk Is It Anyway?.

I also recommend Paul Almond's The Dangers of Hanging Baskets which analyses the impact of regulatory myths such as the supposed banning of floral-display hanging baskets. These silly stories represent damaging challenges to the legitimacy and effectiveness of health & safety regulators.

(The Health and Safety Executive has published a handy checklist. There is no law banning conkers in playgrounds; candyfloss on a stick has not been prohibited; the sack race has not been banned from sports day.)

Lord Young's 2010 review of health and safety regulation is summarised here and you can also examine the BSE/vCJD scare as a case study as well as a commentary on the BSE Report.

It is worth remembering, by the way, that many annoying 'Elf & Safety' prohibitions have been imposed on event organisers by insurance companies worried about their clients being sued by an injured person. Daniel Davies commented that "we appear to have developed an entire secondary and privatised regulatory system run by insurance companies". More generally, some organisations seem to have begun to believe that 'where there's blame, there's a claim' and adopted disproportionately risk averse practices in response. The Secret Barrister's Fake Law contains an excellent chapter discussing these and related issues.

A more general discussion of the effective regulation of large and small firms may be found here and here.

Historical Perspectives

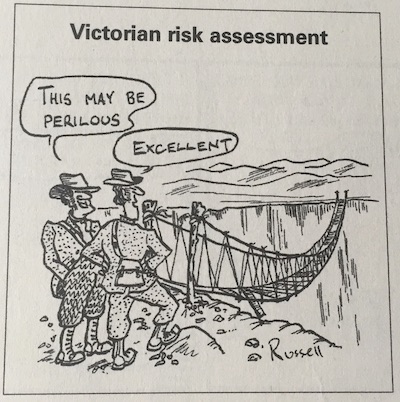

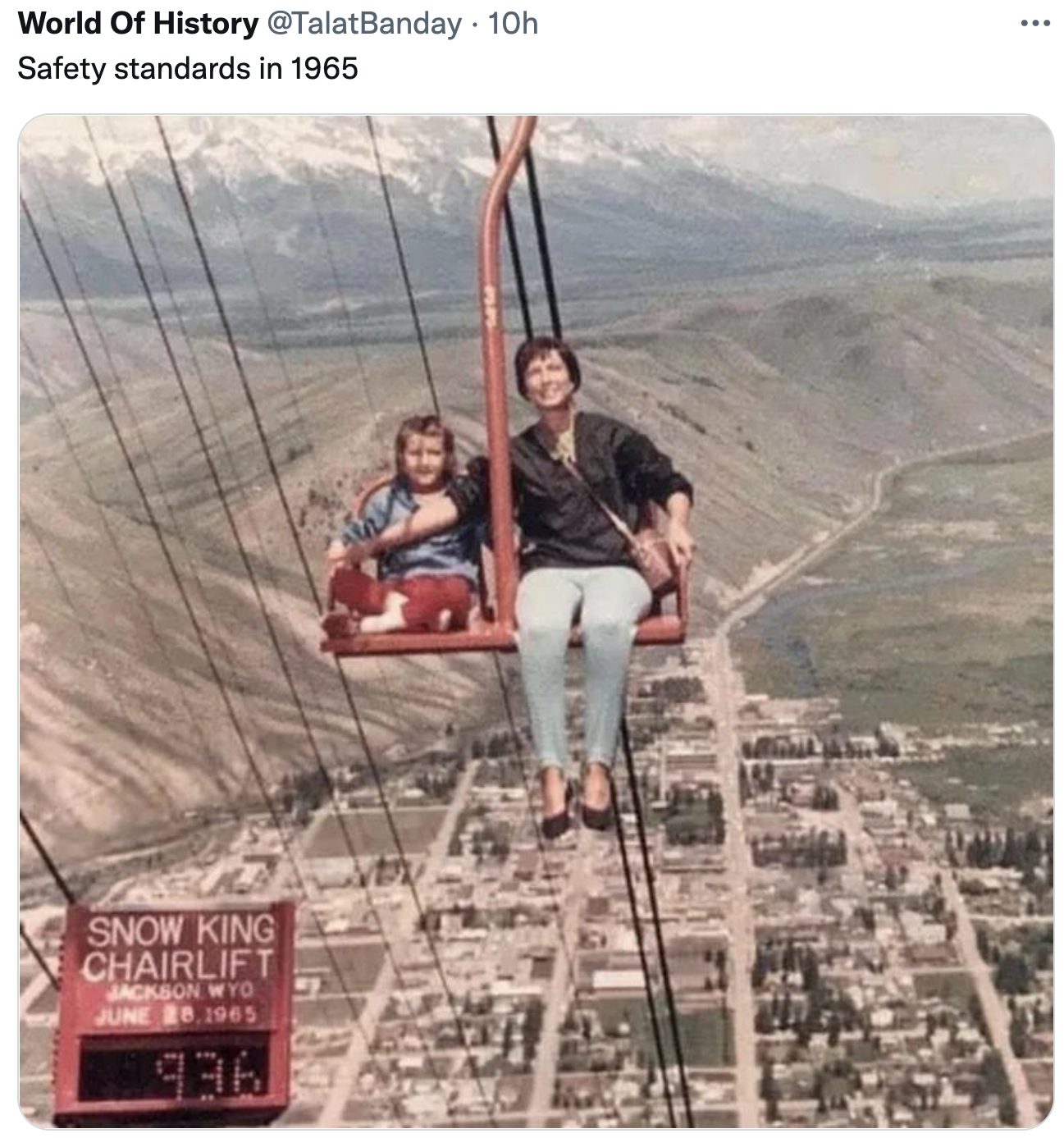

It is fascinating to read Christopher Sirrs' description of the background to the introduction of modern health & safety legislation in his - Accidents and Apathy ; The Construction of the 'Robens Philosophy' of Occupational Safety and Health Regulation in Britain, 1961-1974 . Surely no-one would want to reintroduce the attitude to health and safety demonstrated in this 1964 photograph?

It is fascinating to read Christopher Sirrs' description of the background to the introduction of modern health & safety legislation in his - Accidents and Apathy ; The Construction of the 'Robens Philosophy' of Occupational Safety and Health Regulation in Britain, 1961-1974 . Surely no-one would want to reintroduce the attitude to health and safety demonstrated in this 1964 photograph?

Those interested in longer term trends in this area will wish to read this very detailed Institute of Occupational Safety and Health Research Report written by Paul Almond and Mike Esbester:- The Changing Legitimacy of Health and Safety at work,1960–2015.

I also recommend Paul Almond's Revolution Blues: The Reconstruction of Health and Safety Law as 'Common-sense' Regulation in which Professor Almond criticises the 2010-15 Coalition Government's encouragement of 'common sense' regulation - to the detriment of sensible regulation driven by effective, widely consultative and high quality consultation.

Communicating Risk and Uncertainty

Adults are generally pretty good at assessing immediate risks with which they are broadly familiar. But we are less good at assessing and responding to the longer term risks associated with financial investments, poor diets, climate change and so on.

Part of the problem is that commentators often focus on either the low probability of damage or the high impact if something does go wrong. "Smoking never did any harm to my 85 year old uncle" versus "Smoking kills". This, from Kat Arney, can be a useful metaphor:

Imagine if you took 2 million adults, randomly allocated half of them to drink four double whiskies and sent them all on a 300 mile journey down to Central London, not only would you be well advised to steer clear of them, but you'd also expect more accidents to happen in the group who'd had the Scotch. But you'd also expect many of the drunk drivers to make it to the capital unscathed, and you wouldn't be surprised if even a few of the sober ones had an accident along the way for an unrelated reason.

Road safety campaigners will always focus on alcohol drinkers' increased accident rate and the consequences for families and wider society. Libertarians will focus on the large number who drink the whisky but nevertheless get to London unscathed. There is no obviously correct level of pre-driving alcohol consumption. You need to assess society's (or your own) risk appetite given all the circumstances. You would be very likely, for instance, to set a much lower alcohol threshold if the adult travelling 300 miles were driving a passenger coach or piloting a plane.

Radiation and radioactivity are particularly scary concepts for a large part of the population. Here is a useful note about the link between radiation and cancer and also a review of what happened when radiation and risk came together in the 2001 depleted uranium scare.

Follow these links to access:

- The Cabinet Office's Communicating Risk Guidance

- authoritative guidance on communicating risks which is applicable to virtually any risk bearing issue

- David Spiegelhalter's 2017 paper Risk and Uncertainty Communication .

It is also instructive to learn from the government's mistakes when responding to the 2020 COVID pandemic.

Other Useful Stuff

The website of the Health and Safety Executive which contains interesting documents such as Reducing Risk, Protecting People and the As Low as Reasonably Possible (ALARP) Guidance for HSE staff, both of which provide an insight into HSE's approach to risk management and control.

Follow this link for a summary of basic scientific facts, figures and relationships:- essential reading for all GCSE and A level students as well as civil servants trying to make sense of scientific papers etc.

The Institute of Physics offers a very good, jargon-free website which will answer many of your science-related questions. It is ideal for those questions that you don't like to ask in the office for fear of betraying your lack of scientific knowledge!