There is a huge problem in that all governments, and many other organisations, seem to find it very difficult to learn from previous experience, or to respond effectively to warnings of possible disaster.. There are no doubt many reasons for this but I suspect that part of the problem is that we don't like to dwell on our past mistakes - and "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it". Most public inquiries are implicit admissions of failure, and politicians in particular have little to gain, and much to lose, from the spotlight settling on their previous mistakes.

There are rare exceptions, of course - not least Winston Churchill who asked himself these four questions after the fall of supposedly impregnable Singapore:-

- Why didn't I know?

- Why didn't my advisors know?

- Why wasn't I told?

- Why didn't I ask?

Unfortunately, however, Churchills are rare and possibly becoming rarer. So, unless particular care is taken, even the best after-the-event recommendations will not ensure learning. Typically, only around half of the recommendations made by a formal Inquiry will be implemented. In many cases the corrective actions will either not be taken or will not have the impact intended. One recent example is that the strengthening work recommended as a result of the collapse of Ronan Point in Newham (1968, killing four people) was never carried out at Ledbury Towers, South London. Four tower blocks therefore had to be evacuated when the problem was identified in 2017. And many experts fear that the hacking of a water, electricity, nuclear power or transport installation kills many people despite their having urged governments worldwide to invest more to keep the security of national infrastructure up to date.

This is not to say that formal or informal post-event inquiries are a waste of time. The Mid-Staffs Hospital inquiry, for instance, led to real change. And the Cullen Report into Piper Alpha led to lasting industry-wide systemic change. All the 106 recommendations made were accepted. Lord Cullen said: “The industry suffered an enormous shock with this inquiry, it was the worst possible, imaginable thing. Each company was looking for itself to see whether this could happen to them, what they could do about it. This all contributed to a will to see that something better for the future could be evolved.”

(But there was a worrying report in July 2013 - the 25th anniversary of the Piper Alpha disaster - of a whistle-blower's accusation that the post-Cullen safety representative system was being made a "mockery" because of bullying by some managers.)

It may be that learning is difficult, verging on impossible, until whole industries or whole communities are shocked by what has happened, Piper Alpha shocked the oil/gas industry and several railway accidents around the turn of the century (including Ladbroke Grove) severely shocked that industry, leading to many accident free years. But it does not seem that Grenfell has as yet provided a big enough shock to change the construction industry in a fundamental way., Let us hope that the Grenfell Inquiry team will learn from Cullen and establish a process for the successful implementation of their recommendations and so ensure lasting change. Failure to consider the implementation of recommendations could severely limit their impact.

More generally, this failure to learn appropriate lessons from all sorts of previous tragedies - or to forget such learning soon after formal inquiries have been completed - seems to have been a persistent problem for several decades. (See for instance Dr Kevin Pollock's report for the Cabinet Office on the persistent failure to learn lessons relating to the interoperability of emergency and other services.) No-one, and no organisation, seems to be responsible for following up the recommendations of public and similar inquiries. Here are some extracts from Dr Pollock's conclusions:

Common causes of failures identified within the reports include:

- Poor working practices and organisational planning

- Inadequate training

- Ineffective communication

- No system to ensure that lessons were learned and staff taught

- Lack of leadership

- Absence of no blame culture

- Failure to learn lessons

- No monitoring/audit mechanism

- Previous lessons/reports not acted upon

The findings of this research echo Lord Cullen’s comments in his report on the Piper Alpha explosion, when he set out the basic and common principles required in any system when managing to prevent incidents ... these are summarised as:

- Commitment by top management – setting the resilience standard and philosophy and communicating to staff

- Creating a resilience culture – safety is understood to be, and is accepted as, the number one priority

- Organisation for resilience – must be defined organisational responsibilities, and resilience objectives built into on-going operations, and part of personnel performance assessments

- Involvement of the workforce – essential that the workforce is committed and involved in resilient and safe operations, and are trained to do and do work safely, understanding their responsibility to do so

Conclusion: The consistency with which the same or similar issues have been raised by each of the [many] inquiries [since 1986] is a cause for concern. It suggests that lessons identified from the events are not being learned to the extent that there is sufficient change in both policy and practice to prevent their repetition. The overwhelming number of recommendations calls for changes the doctrine and prescriptions are often structurally focused, proposing new procedures and systems. But the challenge is to ensure that in addition to the policy and procedures changing, there is a change in organisational culture and personal practices. Such changes in attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours are more difficult to achieve and take longer to embed. However, failure to do so will result in the gathering of the same lessons which repeat past findings rather than identifying new issues to address and continuously improve the response framework.

Very similar conclusions were drawn in the IfG's 2017 report on public inquiries. The IfG found that of the 68 public inquiries that had taken place since 1990, only six had been fully followed-up by select committees to see what government did as a result of the inquiry. The report also finds that inquiries take too long to publish any findings, with one in seven taking five years or longer to release their final report. To ensure public inquiries can lead to real change, the report called for:

- government to systematically explain how it is responding to inquiry recommendations

- select committees to examine annual progress updates from government on the state of implementation

- public inquiries to publish interim reports in the months, rather than years, after events

- expert witnesses to be involved in developing the recommendations of inquiries.

The 1982 Kings Cross Fire, which killed 31 people, was another failure to implement recommendations. It emerged after the fire that fire safety recommendations from the Railways Inspectorate had gone unheeded by London Transport eight months before the fire.

it is perhaps best to leave the last word, in this section, to Albert Camus' narrator in The Plague (emphasis added):

"Pestilence is in fact very common, but we find it hard to believe in a pestilence when it descends upon us. There have been as many plagues in the world as there have been wars, yet plagues and wars always find people equally unprepared. Dr Rieux was unprepared, as were the rest of the townspeople, and this is how one should understand his reluctance to believe. One should also understand that he was divided between anxiety and confidence. When war breaks out people say: ‘It won’t last, it’s too stupid.’ And war is certainly too stupid, but that doesn’t prevent it from lasting. Stupidity always carries doggedly on, as people would notice if they were not always thinking about themselves."

Failure to Listen to Warnings

It is depressing how often disasters follow clear warnings ignored or discounted by those in power. Here are some examples.

The Times reported in August 2021 that 'Joseph Naddaf is puzzled, and it is not hard to see why. He was the one man who tried to stop the disaster at Beirut port, the explosion which a year ago this week ripped through the city, enveloping it in flames and smoke, and killed 200 people. The state security major had repeatedly warned his superiors of the impending disaster, his files on the dangers of the ammonium nitrate stashed in Hangar 12 reaching the desk of the president. Yet afterwards he was interrogated, arrested and held in jail for eight months.'

And, now that we have seen the devastation caused by the 2008 financial crisis, we know that Senator Byron Dorgan delivered an amazingly prescient speech on the eve of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999. Eight Senators voted against the Act but most were caught up in the frenzy of deregulation that was induced by a booming American economy and a financial industry that was spending many hundreds of millions of dollars around Washington. His speech is here.

The Danger of Prosecutions

Those who might possibly be blamed for causing a disaster (or their insurers) will fight hard to clear their name, for the civil and reputational consequences can be severe. Legally, though, those truly blameworthy are on weak ground. Formal inquiries will most likely discover the truth, and the courts will ascribe responsibility on the balance of probabilities - 'more likely than not'.

Prosecutions are altogether a different thing. Juries have to be 'sure' - a much tougher test. And the consequences of a criminal conviction are serious and life-changing. Those charged will therefore fight exceptionally hard to avoid conviction, and prosecutors have to work extra hard, and prepare water-tight evidence and arguments, which takes a long time.

Worse still, non-criminal investigations and inquiries are forced to wait until criminal charges are settled one way or the other, or witnesses will be exceptionally cautious in the way they respond to non-criminal investigators' questions.

Prosecutions, such as for corporate manslaughter, are therefore usually very bad news for those mainly interested in understanding the causes of an incident, and avoiding its repetition.

An Independent Accident Board?

It is not too difficult to think of alternatives to lengthy public inquiries which delay both civil and criminal investigation of major incidents. It is vital, for instance, that lessons are learned quickly after air, rail and maritime accidents. Such accident inquiries are therefore carried out by specialist inspectorates under legislation which provides that their reports may not be used to ascribe legal blame. Air accident reports, for instance, carry the following introduction:

The sole objective of the investigation of an accident or incident under these Regulations is the prevention of future accidents and incidents. It is not the purpose of such an investigation to apportion blame or liability. Accordingly, it is inappropriate that AAIB reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose.

David Slater has proposed the creation of a similar independent, trusted, non-conflicted accident board that could create a safe space for an inclusive examination of other major incidents. He notes in particular that it is often not difficult to tease out the main issues. An analysis of the Grenfell Tower fire was produced less than a week after the event.

The Competition and Markets Authority is another useful example of an independent body which carries out complex investigations to tight statutory timescales: six months for merger inquiries, two years for market investigations. As a result, it can impose tight deadlines on the lawyers acting for individuals and organisations that need, or are required, to submit evidence and arguments.

The creation of a similarly powerful investigatory body would not necessarily lead to its conclusions and recommendations being acted upon, but it would almost certainly help because the disastrous event that triggered the inquiry would, at the time of the report, be fairly fresh in everyone's memory, rather than something that happened in the mists of time long, long ago.

The Needs of Survivors and Bereaved

When a catastrophe takes place leaving many dead or injured, or when people are harmed over a number of years due to systemic failure, the justice system must respond. A tragic incident might spur a range of concurrent legal processes: criminal investigations, disciplinary hearings and civil claims may be initiated that share identical subject matter with an inquiry, inquest or both.

These overlapping processes can be confusing for those involved: at worst, layers of legal duplication can fuel the pain of loss. From the perspective of those caught up in the aftermath of the disaster – including victims, witnesses and alleged wrongdoers – the process can be agonisingly protracted. Public inquiries are notoriously time-consuming: the Bloody Sunday inquiry took over 12 years to publish its conclusions and the Independent Inquiry into Child Sex Abuse is onto its fourth Chair. The 1989 Hillsborough stadium disaster has been the subject of an inquiry, an inquest, an independent non-statutory review, an independent pane and a prosecution.

Further, survivors and their families often speak of alienation, mistreatment and whitewashing by the very bodies set up to identify the wrongs they have suffered. Their accounts suggest that inquest and inquiry processes are often highly adversarial and potentially retraumatising. And those with the most at stake may understandably fear that nothing will change once the processes conclude. These issues are explored in a 2017 report on the suffering of the Hillsborough families: The patronising disposition of unaccountable power.

Justice established a Working Party which reported in 2020, recommending the creation of a National Oversight Mechanism to ensure that inquiry recommendations are implemented. Follow this link to read an extract from the report.

Examples

Grenfell Tower

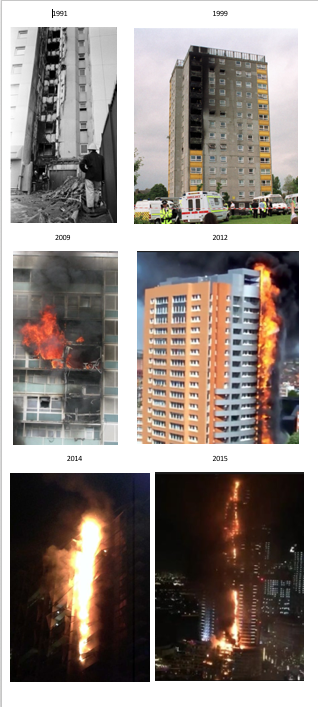

The Grenfell Tower tragedy drew sharp and worrying attention to the fact that there had been at least nine previous similar fires, from which it appears that few if any lessons had been learned, nor had much if any effort had gone into taking the actions recommended by those who looked into the causes of those similar fires - which included:

The Grenfell Tower tragedy drew sharp and worrying attention to the fact that there had been at least nine previous similar fires, from which it appears that few if any lessons had been learned, nor had much if any effort had gone into taking the actions recommended by those who looked into the causes of those similar fires - which included:

- Summerland Leisure Centre, Douglas IoM, 1973

- Knowsley Heights, Liverpool, 1991

- Garnock Court, Irvine, Scotland, 1999 - 1 dead

- Harrow Court, Stevenage, 2005 - 3 dead

- Lakanal House, London, 2009 - 6 dead

- Mermoz Tower, Roubaix, France, 2012

- Lacrosse Tower, Melbourne, Australia, 2014

- Address Downtown Hotel, Dubai, 2015

- Shepherd's Court, Shepherd's Bush, 2016

(Harrow Court is the first picture on the right. Click on the image on the far right to see a larger version of the photos of another six of the above fires.)

Strong warnings had been given by the Fire Brigades Union and others in evidence to the House of Commons Environment etc. Committee as long ago as 1999, following the Garnock Court fire. An opportunity certainly appears to have been missed when that committee reported later that year. The committee concluded that:

"The evidence we have received during this inquiry does not suggest that the majority of the external cladding systems currently in use in the UK pose a serious threat to life or property in the event of fire."

Unfortunately this conclusion appears to have reduced the impact of their subsequent conclusion that:

"Notwithstanding what we have said ... above, we do not believe that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks. The evidence we have received strongly suggests that the small-scale tests which are currently used to determine the fire safety of external cladding systems are not fully effective in evaluating their performance in a 'live' fire situation. As a more appropriate test for external cladding systems now exists, we see no reason why it should not be used."

Institutional Racism

Another 2017 example of failure to learn was uncovered by the inquiry into the murder of Bijan Ebrahimi. The inquiry found that the Bristol police had been guilty of 'institutional racism' - nearly 20 years after the massive publicity that surrounded the same finding by the 1999 MacPherson report into the Metropolitan Police's handling of the Stephen Lawrence murder.

The Sewol

This is of course far from a purely UK problem. The South Korean Sewol Ferry capsized in 2014, drowning 250 students amongst others. The Sewol sank because of greed. Renovations by the owner, and approved by regulators, made the ferry more profitable, but also dangerous. Extra berths made the ship so top-heavy that dockworkers said it would lurch badly when loading or unloading. Emotional promises were made that such things could happen again, but a 10 June 2019 New York Times investigation showed that, five years later, nothing had changed.

Oil Spills

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion killed 11 people and unleashed the worst offshore oil spill in US history. Ten years later all seven members of the bipartisan National Commission set up to find the roots of the disaster and prevent a repeat said that many of their recommendations were never taken seriously and that an equally disastrous spill remained possible. Oil industry leaders and members of the Trump administration were said to disagree.

COVID-19

The whole world clearly forgot the lessons learned from the many reports written following the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak, which in turn followed on from SARS (2003) and MERS (2012) as well as various swine and avian influenzas. The result was an unnecessarily and disastrously severe SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19/coronavirus) pandemic in 2020.

The Plague

Albert Camus imagined a nice example of failure to learn in The Plague.