It is good to see companies meeting the needs of their customers and so growing in size. It is also good to see mergers and takeovers which lead to increased efficiency, greater innovation and improved service to customers. And if companies become so large that they begin to dominate their market, their behaviour can in principle be controlled by the use of Abuse of Dominance legislation.

Abuse of Dominance legislation is, however, far from ideal. It is necessary for the competition authority to identify misbehaviour amounting to 'abuse' which can lead to the levying of fines. Companies and their executives inevitably fight such accusations very hard indeed, and the courts require competition authorities to have strong and compelling evidence. This in turn leads to such inquiries ending inconclusively and/or taking a very long time indeed: 4+ year inquiries are not uncommon. It is also often the case that markets do not work well for reasons which are to do with the history or structure of the market, rather than deliberate misbehaviour by individual companies. Tacit Collusion (aka Tacit Coordination) is, for instance, very common. More detail is in the Annex below.

The good news is that in the UK, (though not in most other countries) it is possible for competition authorities to investigate and remedy problems in markets which do not appear to be working well, including those exhibiting possible tacit collusion, without targeting any individual company:

- The CMA first carries out a Market Study following which it can either make recommendations to the industry or to government (e.g. for regulatory action), or it can decide to carry out a full Market Investigation.

- Utility regulators, too, can refer their markets to the CMA for an investigation, having carried out their own prior study.

(One high profile Market Study - completed in 2019 - concerned the accountancy industry and the very large market share of the 'Big Four' companies in large audits. The CMA worked quickly and made some controversial recommendations to government, but it might have been better if thee had been a more thorough Market Investigation which could have led so the CMA imposing its own remedies, rather than relying on politicians to take on significant vested interests.)

In a Market Investigation, the CMA is required to decide whether there is an Adverse Effect on Competition ('AEC') arising out of an identifiable feature or features of the market. The Authority follows a fairly standard process for all market investigations, which need to be completed within months:

1. The CMA identifies possible theories of harm - i.e. features which may be causing an AEC. It then identifies what evidence would be needed to demonstrate (in the case of each theory) that harm would indeed be likely to result from that feature. This helps to focus the inquiry because the CMA can look for particular evidence, rather than ask every question that comes to mind. Then, if the evidence is found, remedial action can be taken - or, if the evidence is not found, the market can be cleared.

2. The CMA then issues an issues statement which summarises the possible theories of harm and other issues that it intends to consider during the inquiry. The statement doubles as an invitation to third parties (any interested companies, organisations or individuals other than those under investigation) to comment on the market and submit evidence to the CMA. The main parties to the inquiry (the main players in the market) and third parties may also comment on the issues statement if they wish - especially if they think that the CMA may have missed a possible theory of harm, or identified any issues which are in practice not likely to be relevant.

3. The CMA seeks submissions from the main parties. It also requests the submission - from any person - of any evidence and information which it thinks might be helpful.

4. The CMA then analyses all the submissions and evidence and sends a number of working papers to the main parties. These papers summarise the CMA's thinking on key issues, so that the main parties can if necessary challenge the thinking before the CMA's views become too firm.

5. The CMA also publishes its Emerging Thinking so that all interested parties - including the media - can get involved in the debates.

6. The CMA in due course issues its Provisional Findings - a lengthy and detailed document which summarises the evidence and analysis which has persuaded the Commission to reach a provisional view that there is, or is not, likely to be an AEC. If there is no AEC then that is the end of the matter, although the CMA will in due course a publish a more polished Final Report

7. But if there is an AEC then the inquiry in principle proceeds along two parallel tracks:

The main parties are entitled try to persuade the CMA to change its mind either by submitting crucial new evidence or by persuading the CMA that its analysis was misguided.

The inquiry simultaneously enters its remedies phase as the CMA and the parties discuss how the AEC might be remedied.

8. The inquiry is formally concluded by the publication of the CMA's Final Report which confirms (or otherwise) the existence of an AEC and summarises the remedy or remedies which the CMA intends to impose on the participants in the market.

9. It is then usually necessary to discuss and finalise a detailed remedies package. This can take some time but, if agreement cannot be reached, the CMA will impose a detailed remedy by issuing a formal Order, which has the force of law.

Issues

The CMA's powers are in some ways quite extraordinary. They can make Orders which are legally binding on businesses that were not part of the original investigation. For instance they can require a range of businesses to publish or publicise particular information which the CMA believe would make the market work more effectively. And they can force companies to sell large chunks of their businesses. For instance, they forced BAA (the owner of Heathrow Airport) to sell both Gatwick and Stansted. BAA's lawyer claimed - probably accurately - that this was "just about the largest individual forced transfer of land since the Reformation".

But market investigation powers can be very useful (and necessary) when facing the power and complexity of today's 'Big Tech'. The EU's Digital Market Act accordingly gives the European Commission very similar powers.

Utility regulators might be expected to refer markets pretty promptly to the CMA once they recognise that their own powers might be insufficient. In practice, of course, they tend to hang onto such cases far too long as they (a) find them interesting and exciting, and (b) they don't like the possibility that the CMA might not agree with their strategy for the market in question.

In particular, Ofgem has been strongly criticised for its unwillingness to refer the energy market - which may well exhibit tacit collusion - for investigation by the CMA. The reference was eventually made in early 2014.

In contrast, Ofcom's (and its predecessor's) reluctance to refer the broadband final mile was better understood, despite BT's clear unwillingness to allow its broadband competitors to access its exchanges and use BT's wires to provide competitors' customers with access to non-BT broadband services. This was because a near two year Market Investigation would have been very complex (Ofcom believed that there were 18 separate 'markets', though they later decided that there were many fewer than this). An investigation would also most likely have slowed the pace of change in an otherwise rapidly changing industry, as all the key players awaited the result of the inquiry. In the event, Ofcom and BT came to an agreement in 2006 intended to ensure that rival telecoms operators had equality of access to BT's local network, resulting in the creation of BT Openreach.

The CMA's predecessor, the Competition Commission (CC), also took steps to speed up its handling of Market Investigations and announced in April 2009 that it would in future aim to complete such investigations within 18 months rather than the statutory maximum of 24 months. The Government announced in March 2012 that the statutory time limit would itself be reduced to 18 months (extendable to 24 months) and that the new Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) would have a (new) power to investigate practices across markets. (The CC had previously found some anti-competitive practices to be common across certain markets (e.g. early settlement terms in the PPI and Home Credit markets, and the sale of secondary products at particular points of sale in the PPI and extended warranties markets).)

Recent High Profile Market Investigations ...

... have included:

Supermarkets

Airports

Payment Protection Insurance

Local Bus Services

Annex - Tacit Collusion

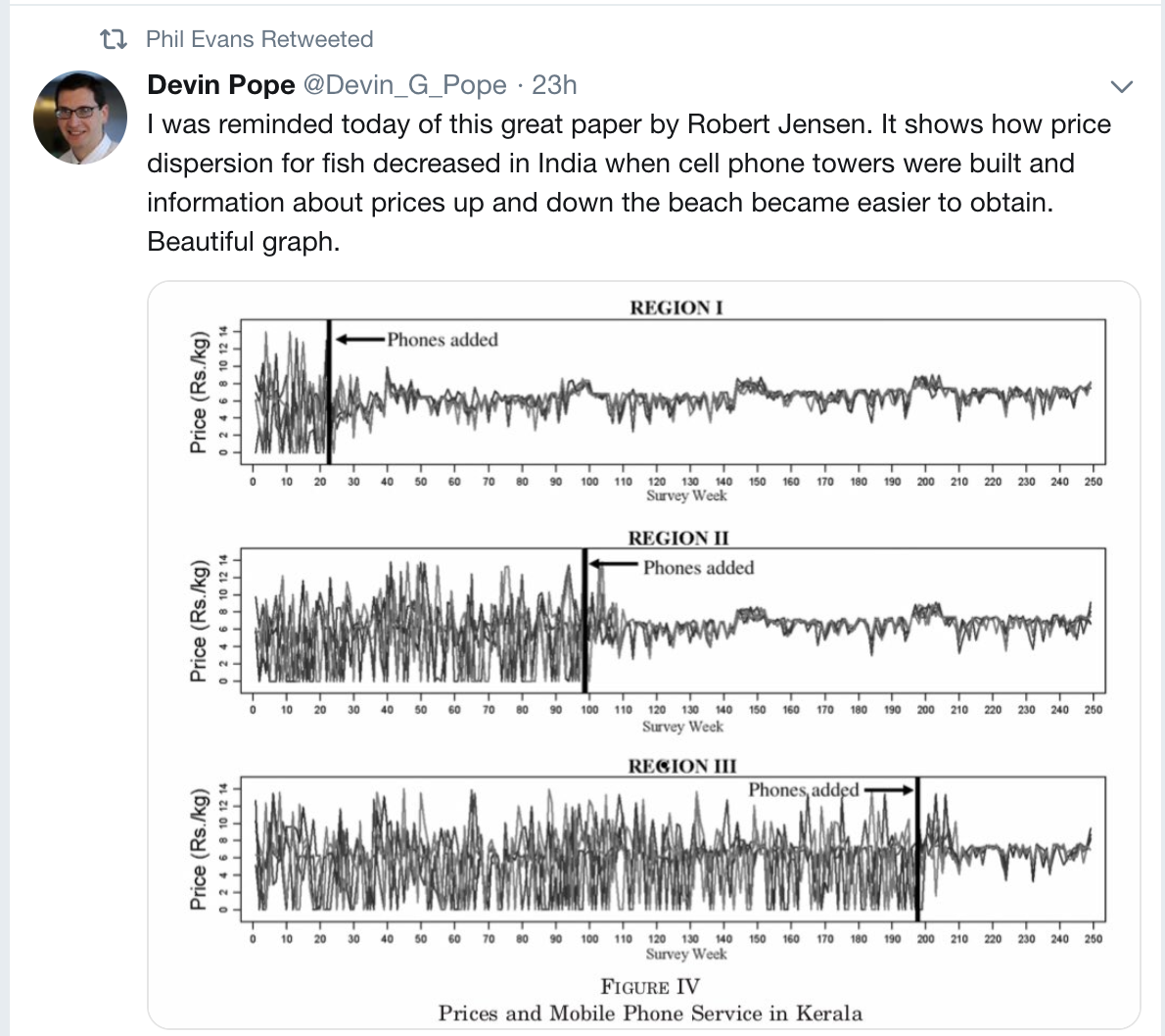

As this example shows, different businesses will charge similar prices for similar products if they (and their customers) can easily compare those prices.

But this does not mean that all the businesses will compete hard by reducing their prices. Indeed, the above charts show that prices settled well above the lowest prices that had previously been available to customers.

A more worrying example of this sort of behaviour occurs when there are relatively few firms in a market and they are all making good profits, perhaps because their costs have all fallen. In these circumstances it may be obvious to all the firms that a price reduction would not help them gain customers from their competitors, but would simply result in their competitors lowering their own prices. So prices remain high and everyone wins - apart from the poor customers of course!

Tacit collusion also works to disadvantage consumers when a company with a sophisticated pricing algorithm instantly matches its rivals' price cuts. Its competitors then have no incentive to lower prices. See also item 12 (price matching) here.

(A more technical explanation reads as follows:

Coordinated effects may arise when firms operating in the same market recognise that they are mutually interdependent and that they can reach a more profitable outcome if they coordinate to limit their rivalry. Such coordination can be explicit or tacit. (Usually illegal) explicit coordination is achieved through communication and agreement between the parties involved.

Tacit coordination is achieved through an implicit understanding between the parties, but without any formal arrangements. Such coordination may arise when market conditions are sufficiently stable and rival firms interact repeatedly so that they may be able to anticipate each other’s future actions, allowing them to establish an internally and externally sustainable coordinated course of action, without resorting to direct communication and information sharing or agreeing expressly to align incentives and expectations.)