This page was archived in 2022 and does not report any subsequent developments.

Water comes free, of course - in small quantities from the sky. But water companies spend a lot of money bringing it to our homes and businesses, and taking it away again in the form of sewage. Some companies do this more efficiently than others, so there has been plenty of scope for the water regulator, to force down prices and improve service quality etc. However (like railways) it is very hard to introduce competition into this naturally monopolistic industry - there can be only one pipe to each building. Therefore, although water companies' prices are set by Ofwat (in England & Wales) in the normal RPI-X sort of way, the economic regulation of this industry has a number of interesting features, summarised below.

By way of background, this book review (of Ian Byatt's assembled lectures etc.) provides an excellent short history of water regulation in the UK.

Click here for an introduction to utility regulation.

Large Environmental Costs

Water pricing, like energy pricing, contains substantial government-imposed environmental costs. The industry (and therefore its customers) therefore pay a great deal of money to ensure that drinking water is very pure, rivers and beaches are clean, and so on. Such standards have been driven up as a result of EU Directives, often encouraged by UK Environment Ministers such as Michael Meacher in the late 1990s, and following very limited scrutiny in member states. Ofwat has no choice but to pass these costs on to consumers, which it does by adding a '+K' factor to the normal RPI-X formula.

Sceptics, Ian Byatt and myself included, have often wondered whether these costs are justified. But it is certainly true that our drinking water is now much less acidic than it was, and so dissolves smaller quantities of harmful lead. It is also less likely to contain harmful bugs such as cryptosporidium. And is is less likely to be coloured. All these are good results, although I am not aware that these benefits have been compared with the costs, which have been substantial. New pollution control obligations cost over £8bn between 1999 and 2004, whilst improved drinking water quality, and improved sewerage collection and treatment, will have cost a further £3bn+ and £8bn+ respectively in the period 2005-2015. The 26km 'London Supersewer' is likely to cost over £4bn which will be passed on to Thames Water customers, whose bills will rise indefinitely by £25pa. There are many who regard this expenditure as unnecessary, as well as many stout defenders of the need to reduce the number of times that London's sewers overflow into the Thames.

Combined water and sewage bills in England & Wales had accordingly typically risen by over 60% in the 10 years to 2013. The average bill in 2013 was £388 pa of which £123 was the cost of new infrastructure, driven by environmental legislation, £103 was returns to investors, £12 was tax and only £150 was operating expenditure. But there is a large regional variation because environmental costs depend very much upon the extent of a region's rivers and coastline. Average bills in the West Midlands were the lowest at only £335 in 2013, whilst the highest was £499 in the far South West. The disparity subsequently grew even wider, forcing the government to step in and subsidise Cornish water bills by £50pa.

The Foundation for Water Research has published a very interesting guide entitled Regulation for Water Quality: How to Safeguard the Water Environment. You can download it from the web here.

Competition

As so often, weak competition means that the water industry remains much less innovative and efficient than it might be. Even at the national level, it is noticeable that the often rain-soaked UK frequently has to resort to Summer season hosepipe bans, whereas the inhabitants of Las Vegas, although surrounded by desert, remain free to water their many luscious lawns. But it has also become clear that there is no overriding reason why both business and domestic customers should not be able to benefit from competition to supply their water thus putting pressure on the industry to reduce the cost involved in billing, mending leaks and so on.

Indeed, Scotland was the first country in the world where business customers had an opportunity to choose their supplier. All non-household customers can now change their water supplier. As well as commercial companies, this includes public sector organisations such as schools, hospitals and council offices. There were 10 licensed suppliers in 2013.

Ofwat had for some time been a relatively weak player when it came to promoting competition in England and Wales, although it became more active in the period through to 2013 despite being shackled by weak legislation. Also, it had introduced separate wholesale and retail price controls, which encouraged competition for business customers outside the transmission network - see the Albion Water saga below. But the Water Act 2014 at last facilitated switching by business customers, in England only, as from April 2017. (The Welsh Government has yet to be persuaded of the virtue of competition in this industry.) It was not expected that competition would lead to sharp reductions in water bills but it would very likely drive improvements in customer service, including assistance with using water efficiently. It was interesting, though, that newspaper reports suggested that there was quite lively price competition by 2020, with a large number of dedicated suppliers eating into the market shares of the old regional monopolies. But there remained a large (though reducing) number of complaints about poor service. The Consumer Council for Water said that "Too many [companies] were quick to make excuses and slow to resolve complaints.".

Ofwat also announced, in September 2016, that it would like to open the domestic retail water market in England to more competition. Under their proposals, firms could buy water in batches from existing providers and sell it on to households, and Ofwat believed that greater competition could mean innovation and lower prices. Companies could also offer bundles of services, selling gas, electricity or broadband alongside water. Ofwat did not expect that greater competition would have a big impact on bills, with an average annual saving of maybe only £8. But it should lead to better service. "The uncomfortable truth is that, when it comes to retail offers, water companies provide an analogue service in a digital age. ... For instance, at the moment only two of the water companies in England let their customers manage their bills using an app. That's the kind of thing we'd expect to change and see real innovation." However, as with energy and personal banking, opening up the market would only work for customers if switching was made "as hassle-free as possible". But the change would need Government approval, and it was not clear whether that would be forthcoming.

The most noticeable example of competition outside Scotland, had been Albion Water's use of the Competition Appeal Tribunal to enable it to supply cheap (non-drinkable) water to Shotton Paper and Corus Steel Shotton near the River Dee in North Wales. (Shotton Paper alone consumes nearly 20 million litres of water a day!) The interesting thing was that Albion was in effect a virtual supplier. Nothing changed in the real world apart from the legal ownership of the water as it flowed from river to major customer. Albion wanted to buy water at a reasonable price from United Utilities, the company that already extracted the water from the River Dee, and they wanted to pay Shotton's existing supplier, Dwr Cymru, a reasonable price for then transporting the water to Shotton. But Albion reckoned that, after adding these two prices together, they could still hugely undercut the price that Dwr Cymru charged e.g. Shotton Paper. In other words, Dwr Cymru were, in Albion's view, making excessive profits in supplying the two Shotton companies. But Dwr Cymru refused to offer a reasonable price to Albion, who then appealed to the Competition Appeal Tribunal. The CAT supported Albion and found Dwr Cymru guilty of abusing their dominant position, eventually awarding Albion nearly £2m in damages.

- It is interesting to note that (unlike Dwr Cymru) Albion Water went out of their way to help Shotton Paper use significantly less water in their processes, and so saved their customer a lot of money. The cost savings were shared between Albion and its customer - an excellent example of how competition can work to the advantage of both the customer and the entrepreneurial supplier.

But there is another side to this story in that Dwr Cymru's Ofwat-approved prices were presumably cross-subsidising some of its customers at the expense of the two Shotton companies. Shotton Paper, understandably enough, wanted to stop this and therefore strongly supported Albion's attempt to insert itself into the supply chain, albeit without any accompanying physical presence. But the result may well be increased prices for other Dwr Cymru customers.

Financing and Profitability

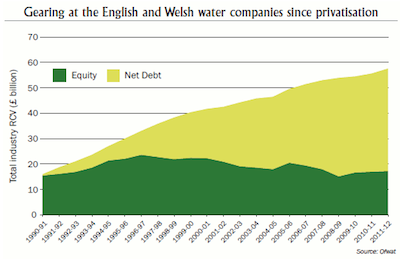

The water industry has financed its huge capital expenditure (£108 billion from privatisation in 1989 to 2013 - see further below) by borrowing rather than through raising share capital - see chart on left. This trend has been encouraged by very low interest rates. This has resulted in three arguably undesirable consequences:

The water industry has financed its huge capital expenditure (£108 billion from privatisation in 1989 to 2013 - see further below) by borrowing rather than through raising share capital - see chart on left. This trend has been encouraged by very low interest rates. This has resulted in three arguably undesirable consequences:

- Water companies' prices are linked to inflation, as measured by the RPI, and have therefore been rising quite steadily. In contrast, their financing costs, now predominantly linked to very low interest rates, have been falling. The industry has therefore become surprisingly profitable, much to the annoyance of the regulator on behalf of customers.

- Ofwat is also concerned that the financing structure is too risky as losses would quickly wipe out many companies rather limited equity bases, leaving them insolvent. This has happened before, for instance in the form of the 2000 break-up of Hyder/Welsh Water. A separate but related concern is that the companies' investors may be too focussed on tax-efficient cash-flow, and reluctant to make the necessary future capital investment.

- The companies pay relatively little UK tax as their profits (before financing costs) are mainly distributed to overseas creditors (bond-holders). This reduces their UK profits (net of interest payments) and so their corporation tax bills are quite modest, and their overseas investors do not pay UK tax on the interest that they receive.

These issues were given some publicity in June 2013 when Jonson Cox, the new Chair of Ofwat, drew attention to the low tax payments. In a letter to the FT, he said that 'This is not for Ofwat, but may be morally questionable in a vital public service'. This may be true, but most senior regulators refuse to comment on issues, such as tax policy, for which they have no responsibility. Be that as it may, this comment was mild when compared with this paragraph earlier in the same letter:

'Ofwat welcomes long-term responsible investment in our sector, and wishes to avoid any shorter-term focus that "private equity" style structures can encourage. Customers benefit from an efficient level of debt, and the related tax relief, in the regulated entity. It is reasonable that some of the current gains from unexpectedly low debt rates and high RPI levels should be shared with customers as should future outperformance from factors beyond management control. Otherwise we will set the rules.'.

Mr Cox was clearly aiming to change behaviour by making his concerns clear and expecting the industry to respond, much as the Governor of the Bank of England used to be able to affect behaviour in the City of London 'by raising his eyebrows'. Mr Cox's approach certainly raised other eyebrows elsewhere in the regulatory community. But - to his credit - he had an early win when six water companies announced in February 2014 that they would not be raising prices in 2014 as much as they were allowed to do under the current (soon to expire) price control. Future pricing will be addressed via the new post-2015 price controls which would be imposed during 2014. It was even thought that the regulator might impose immediate P0 price reductions because the industry now has lower financing costs. (These are known in regulatory circles as the WACC: the weighted average cost of capital.)

By way of example, Thames Water has c.£10bn of regulated assets (i.e. its RCV - Regulatory Capital Value, or RAB - Regulatory Asset Base). Its debt is around £7.7bn so dividend payments of around £230m pa offer c.10% return on its apparent equity of £2.3bn. This very high return is seen as low-risk and so leads to share markets valuing the company at over £12bn, thus reducing the dividend yield to more like 5%. Other noticeable premiums were seen when Northumbria Water was bought at a premium of around 30% in 2011, and an unsuccessful takeover bid implied a 36% premium for Severn Water in 2013. Regulators inevitably go on high alert when they see shares trading at a significant premium to their RCV/RAB, and see this as a sign that the industry's retail prices are too high.

Equally, high dividend yields might also be seen as an inevitable consequence of high gearing (i.e. high debt/equity ratios) or - put another way - an inevitable consequence of the companies being perceived by investors as being high risk. This is another reason for regulators to take a special interest. But do investors realise how risky the shares are? It is possible, for instance, that the majority of investors are insufficiently focussed on the risk of a tough price control plus licence conditions which require substantial capital investment. A tough price control may well sharply reduce companies profits, so sharply reducing their share prices (does anyone care?) or even forcing them into insolvency - in which case more would certainly care.

But are the profits such a big deal? Again taking Thames Water as an example, dividends are around £25pa per each of their c10m customers. It may be hard to make a big dent in this without scaring away investors.

See below for the National Audit Office's views on these issues.

Customer Involvement

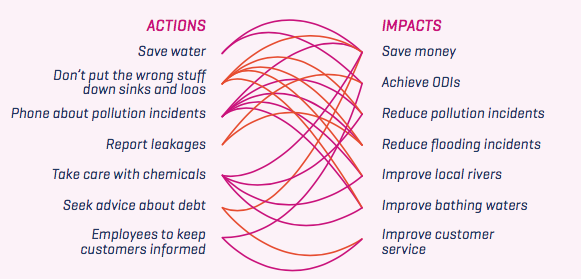

Ofwat are keen to encourage the active involvement of customers in the development of the water industry. The diagram on the left summarises the linkages that Ofwat highlight. (ODIs are Outcome Delivery Incentives that Ofwat have incorporated in industry licences.) More detail may be found in their 2017 Consumer Participation Report.

The Special Merger Regime

The water industry regulator, Ofwat, needs to be able to compare the costs and efficiency of the different water companies, and its ability to do this is reduced if they are allowed to merge. Unusually, therefore, all significant water industry mergers are investigated by the Competition and Markets Authority even though they cannot lead to a substantial lessening of competition. The law therefore requires the CMA to decide whether the merger may be expected to prejudice the ability of Ofwat to make comparisons between different water enterprises

Corporate Governance

Jonson Cox, Ofwat's new Chair from 2013, has expressed concern about the industry's corporate governance, another area which for which he has no direct responsibility, when he said that 'We have not yet found a regulated water company that fully complies with the UK corporate governance code or satisfactorily explains why not. Ofwat's approach is to become less intrusive, and to allow companies opportunities and incentives for greater ownership of their business plans. This requires that boards act in customers' interests. [but] Companies with structures or behaviours that risk public legitimacy cannot benefit from less intrusive regulation.' Again, many will agree with Mr Cox, but others will be concerned that, if a regulator discourages one particular commercial behaviour, then they have to take responsibility for doing so, if the alternative turns out to have unintended and undesirable consequences.

He returned to the charge in June 2017. Here are extracts from his article in Utility Week aimed mainly at Thames Water but with a warning for others (emphasis added):

'During my five years here, we have … refused an unjustified request for a price increase of £30 per customer in the depths of the recession. We took action against Thames Water in 2014 for misreporting, and secured a package worth £86 million for its customers. Following our intervention this year after a spate of serious bursts, Thames will invest almost £100 million more to improve its trunk mains assets.

To cap all this, Thames has just announced that it failed its leakage target for 2016-17 by a huge margin. We have already launched an investigation using our regulatory powers, on top of the significant automatic penalty that Thames Water has incurred by failing to deliver the performance that customers have paid for.

Given all this, we see an urgent need for Thames Water to make a step change in the way it operates and behaves. The company has new members of the management team and new investors. The previous ultimate controller, Macquarie, has sold out to Canadian Borealis and Middle-Eastern Wren House, whom we welcome to the sector. Responsible investors can benefit from helping us drive performance up and prices down.

We are asking the company, with new investors’ support, to adopt the following steps:

- Far-reaching improvement in its communication with all the company’s customers: using the right channels at the right time. Thames Water serves a diverse and vibrant community, which operates around the clock. It should be leading the way in customer communications.

- An annual audited statement from the Board, to sit in front of financial statements, focusing on how the company has set its aspirations and performed for all those it serves. This will illuminate how well Thames Water is delivering for everybody who depends on its services.

- Transparency and clarity about the financial returns to the company’s investors each year. This requires a clear comparison in the annual report between the financial flows under the complex highly-leveraged structure the company has chosen and what those returns would be under the more conservative structure we use for assessing all companies.

- A prompt review of the Board composition to ensure a standard of independence, that the Board can hold the company to delivery of its promises to customers and that the Board can win and maintain public trust.

- Demonstrate that management rewards give appropriate weight to performance for customers as well as financial performance, and explaining transparently how the performance standards have been set and assessed each year.

I call on the company to adopt these five commitments quickly, and discuss with us how it will meet them. We may ask the same of others in the industry too, as we evolve our ground-breaking approach to reforming Board leadership in public service providers.

It’s a privilege for a company to hold a monopoly franchise, in perpetuity. ... We challenge companies to do the very best for the communities they serve and to provide clarity and transparency so that customers have the information they need and the service they expect.'

But ... Thames Water were in 2020 again named by Ofwat as 'the worst water company in the country' which rather suggests that the regulator either has insufficient powers, or doesn't know how to use them effectively.

Leaks

An astonishing 3.3 billion litres of treated water - 20% of all English/Welsh treated water - was being lost through leakage in 2017, at least in part because - as critics such as WWF pointed out - "it is cheaper to drain a river than fix a leak".

Ofwat sets targets for leak reduction, and fined Thames Water £8.55m for missing its target in 2016-17. Leaks in TW's area meant that, it lost on average 180 litres a day for every one of its properties - a quarter of the water that entered its system! The fine would be paid by a once-only reduction in customers' bills of c.£2 per household - but it was small beer compared with TW's profits of over £600m.

The FT reported in October 2017 that TW replaced only 9.4km of its trunk mains in the year to February 2017 against a target of 26km. It would take 357 years to renew the network at the current rate. Time for tougher regulatory action, surely?

Obstruction?

The water industry seems to be more likely than other regulated sectors to exhibit rotten behaviour of various sorts. In 2020, for instance, three employees of Southern Water were convicted of obstructing the collection of data by the Environment Agency which was investigating the discharge of raw sewage into rivers and onto beaches in south-east England. The company was subsequently fined £90m for deliberately dumping billions of litres of of raw sewage into the sea. The sewage had been secretly diverted away from treatment works so as to save costs and penalties. The activity was permitted by at least some of the company's directors.

Other Developments

Ofwat announced its provisional 2015-2020 price controls in August 2014. On average, prices would fall at 1% a year in real terms - i.e. the price control formula was RPI-1. The underlying formulae allowed significant price rises to fund significant expenditure, broadly balanced by reductions to allow for lower financing costs. The net result, from a customer's point of view, was a good deal better than in previous years, even if the price reductions were hardly dramatic, given past increases.

Ofwat kicked off the next price review in 2018 by announcing yet further intrusive attempts to change the behaviour of water companies, including

- requiring the companies to explain how their dividend policies and executive pay are linked to performance, and

- strong incentives to reduce their dependence on debt financing.

It will be interesting to see if the companies push back against this further broadening of the regulator's sphere of influence. But there are early signs that then price controls will be tough.

But executive pay remains generous, given the industry's risk free revenue stream. (It was hardly amongst those worst by by the COVID-19 pandemic.) Sarah Bentley was in 2020 appointed Chief Executive of Thames Water on a salary etc. package worth over £3m pa. Even worse, in some ways, her predecessor Steve Robertson received a £2 million ex gratia payment, on leaving the company, because he had not received any bonuses during his three year tenure due to the company's chronic failure to reduce its leaks.

Notes:

1. A government Review of Ofwat and Consumer Representation in the Water Sector, led by David Gray, was published in 2011. However, it did not recommend any major changes in the way the industry was regulated.

2. The National Audit Office published a report on Ofwat's 2014 price controls in October 2015. It was generally complimentary but concluded that 'companies made net gains of at least £800 million between 2010 and 2015 because of unexpected falls in borrowing costs and the corporation tax rate. Customers would have benefitted if they rather than the companies had borne these risks, though they could have lost out if borrowing costs or tax rates had risen. We consider that the price cap regime does not balance risks appropriately between companies and consumers, and so does not yet achieve the value for money that it should.' Comment: This criticism was not addressed solely at Ofwat. It was NAO's view that most if not all economic regulators who had set the cost of debt in price controls from around 2000 had not done so in a way which had benefited customers. More detail is on my price control web page.

3. The Environment Agency was severely criticised in early 2016 following severe flooding in the North of England. Similar criticisms had previously been leveled at the agency following flooding in the Thames Valley and the Somerset Levels. Commentators pointed out that the agency had suffered significant budget cuts and could not borrow, for instance to fund flood defences. There was perhaps a case for returning to the long-gone days when water companies were responsible for flood defence in their areas. It also seemed likely that the agency was simply too large and had too many functions, so that its Board could not bring sufficient informed attention to individual problems such as flood protection. Click here for a more detailed discussion of this subject.