The Gordon Brown/Treasury-controlled 2005 Hampton Review recommended the consolidation of 31 national regulators into seven thematic bodies. These were in due course to include the Equality and Human Rights Commission and the Care Quality Commission. But this was in practice just one further step along the Big is Beautiful road which had begun with the creation of bodies such as the Financial Services Authority and Ofcom. It was nevertheless probably inevitable that some or all of the super-regulators would in due course be accused of being one or more of over-large, over-bearing, out of touch, over-expensive and employing front-line staff who are unfamiliar with the full breadth of the organisation's regulatory remit. The main difficulty is that there is no way that the Boards, Chairs or Chief Executives of these large organisations (most of whom are excellent individuals) can sensibly lead such complex and diverse institutions where there are negligible economies of scale and arguably severe diseconomies.

The Chairs and Chief Executives of super-regulators do not, in particular, have sufficient time to offer the strong, politically aware but risk-averse leadership that is needed within regulatory institutions - nor can they sensible monitor the detailed implementation of their strategies even though a principal characteristic of regulation is that 'the devil is in the detail'. Ofgem (itself the result of a merger of the previously independent gas and electricity regulators) is still a relative minnow (at c.300 staff) compared with some other regulators but it alone published 17 documents and had 8 live consultations in one week in late 2009 just before this web page was first published. There was no way that their Board could have been taking a serious interest in this activity. Imagine, then, the difficulty of managing the Financial Services Authority (2600 staff), Ofsted (2300 staff), the Care Quality Commission (2000 staff) or even the Commission for Human Rights and Equality (EHRC - 500 staff).

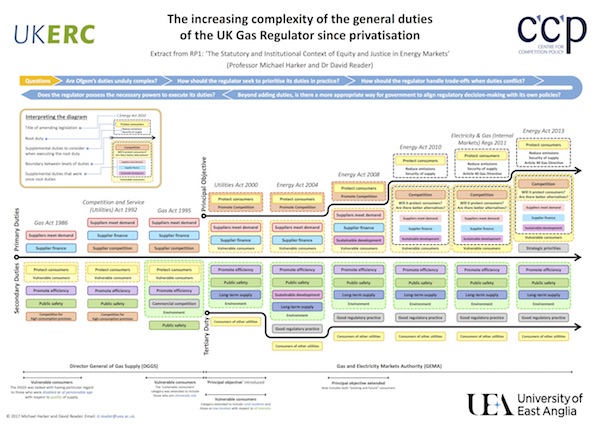

It is also relevant that politicians regularly heap additional duties on the larger regulators. The following chart has been prepared by the Centre for Competition Policy at the University of East Anglia and brilliantly shows how the energy industry regulator Ofgem now has a tottering edifice of Principal Objectives, Primary Duties, Secondary Duties and Tertiary Duties in respect of the gas industry - and it has another quite separate set of objectives etc. for its regulation of the electricity industry. (Click on the chart to view it as a large scale poster.)

A smaller but telling example of politician-inspired regulatory creep was Select Committee Chair Nicky Morgan who in 2019 criticised the Financial Conduct Authority for refusing to start overseeing financial institutions' compliance with the 2010 Equality Act. The regulator politely pointed out that "ensuring compliance with the Equality Act is generally beyond out expertise as a financial services regulator".

It follows my comments, below, about individual regulatory bodies are in no way a criticism of their Board Members or their staff. But it was not at all surprising that:

- The 2008 financial crisis highlighted the ineffectiveness of the Financial Services Authority which had surely got just too big and had been asked to handle just too many issues. A subsequent report noted that 'the FSA Board did not play any operational role in decisions relating to the supervision of specific firms'. and that 'FSA senior management were distant from day-to-day supervision. Senior management did not provide sufficiently clear direction to front-line supervisors, track progress or monitor issues over time. (Click here for a more detailed discussion of this and other regulatory disasters.)

- Ofsted came under severe scrutiny in the light of its role in monitoring the performance of Haringey's Children's services in the run up to the death of 'Baby P". As The Guardian reported in December 2008: " ... questions are also being asked - by the public and social workers put on the defensive - about Ofsted's part in the scandal. Next week [Ofsted's chief inspector of children's services] will appear before a Commons committee to explain how inspectors judged Haringey to be improving two years ago, under exactly the same process that reported such a devastating a judgment this week. Last year a largely data-based review of the entire council judged it "good". In her first interview since the verdict on Baby P was returned, [the Chief Inspector] admits for the first time to failings in Ofsted's oversight of Haringey council, acknowledging that officials in the local authority where Baby P died were able to "hide behind" data last year to earn themselves a good rating from inspectors just weeks after his death."

- Ofsted then hit the headlines once again November 2009 when The Guardian reported that the super-regulator "is facing a crisis in public confidence as it comes under a series of attacks on its authority this week, with the watchdog accused of being "flawed, wasteful and failing" ... Its new inspection regime is accused of forcing social work departments to focus on passing inspections instead of looking after children, giving good schools mediocre ratings on routine technical matters - such as fences not being high enough - and more claims that sub-contracted inspectors are not fit for the job. Pressure further intensifies on the watchdog as a former chief inspector of Ofsted, Sir Mike Tomlinson, today suggests it is struggling after a major expansion two years ago to include responsibility for inspecting children's services as well as schools and childcare."

- And Ofsted was criticised yet again, in 2010, after it failed to spot serious problems at a Plymouth nursery, where a worker Vanessa George sexually abused a number of small children. Critics said that Ofsted's inspection regime was basically a tick-box exercise, and that there was no mechanism through which it could receive reports of concern from e.g. the local authority. Equally, of course, the authority's staff may have been insufficiently assertive.

- The early years of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (the merged anti- sex, race and disability discrimination bodies) was dogged with controversy and several of its Commissioners resigned. Many years on, it has still not successfully combined the three bodies, all with very different cultures and ways of operating.

- Ofcom was the subject of a broadly positive National Audit Office report in November 2010, but the NAO could nevertheless not say that Ofcom was good value for money for its £133m budget, despite costing 27% less than its predecessors, because "it needs a better articulation of the intended outcome of its activities and how its work achieves those outcomes".

- The Care Quality Commission was discovered to have over-exagerated its achievements when it claimed, in 2010, to have been instrumental in closing down dozens of poor care homes. More seriously, the CQC's 'light touch' approach meant that various scandals involving the appalling treatment of the elderly and people with learning disabilities were exposed by the media or other organisations, and not by the CQC. Its Chief Executive, Cynthia Bower, resigned in February 2011 following a less than enthusiastic National Audit Office report and in advance of a critical Public Accounts Committee report.

- (My personal impression was that the CQC was set up to fail. It started life as a very touchy-feely organisation which lacked the hard sceptical edge needed by any effective regulator. And then extra responsibilities were added time after time, so that it became unmanageable. Cynthia Bower and immediate colleagues were people of integrity, committed to public service, and did not argue when asked to take on yet more and more work. They were probably therefore the wrong people for a perhaps impossible job. Their successors were encouraged to abandon light touch regulation and the organisation appears to be gaining credibility, although it remains over-large and over-stretched.)

- The Environment Agency was severely criticised in early 2016 following severe flooding in the North of England. Similar criticisms had previously been leveled at the agency following flooding in the Thames Valley and the Somerset Levels. Commentators pointed out that the agency had not only suffered significant budget cuts but also had too many functions, including environmental protection, the regulation of water supply and river quality, and associated enforcement activity, as well as flood defence.

- Even smaller Ofgem has not been immune from criticism, for instance for failing to tackle tacit collusion amongst energy suppliers and for failing to achieve refunds totaling £70m for over-charged Npower customers:- refunds which were eventually won by the apparently much weaker consumer watchdog, Consumer Focus.

Shared Services

Changing the subject slightly, it is worth noting that Ministers often encourage government departments and agencies to share their back office services such as IT and HR. The aim is to reap economies of scale. But Thomas Elston of the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford University has pointed out that there are a number of reasons why such initiatives might be counterproductive, such as:

- You have to spend to save, for instance by investing in compatible IT systems and re-designing internal processes

- You have to invest in management and inter-agency coordination and consultation

- Standardisation can create unforeseen challenges, both in achieving it and then in avoiding undue inflexibility.

I would add that, as a Chief Executive, I personally hated sharing my IT and HR etc services with other organisations, mainly because I could no longer control, including quality control, these key parts of my organisation. (You don't find private sector companies sharing services.) I strongly suspected that those colleagues who were happy to share such services with other agencies were not actually very interested in management, and rather glad to delegate the control of these non-policy functions to others.

Notes

It is well established that if a building contains more than 150 people they are less likely to work together as a team. 150 is known as the Dunbar Number after the person who first researched and publicised this rule of thumb.