Energy Regulation became a whole lot more political after the 2010 General Election. The first battleground was ...

Switching Rates

Only 30% of customers at the time of privatisation had never subsequently changed supplier - so 70% had switched. However, switching rates fell after 2008 whilst prices rose sharply. Rather than admit the real reasons why prices were rising (i.e. government policy) both politicians and Ofgem were tempted into blaming suppliers - which led to their trying to find ways of encouraging competition between suppliers, including by making their prices more easily comparable.

At one level, this is a good thing. No market can work well if customers cannot easily compare the prices of different suppliers. But low switching rates may in practice be caused by all sorts of reasons. It can be time-consuming to compare tariffs, the gains may be quite small, you may already be locked into a long term deal, and you may be switching to a company which is just about to increase its own rates. Industry experts are therefore pretty nervous of government or regulatory intervention in this area. Indeed, competition will be hindered if suppliers cannot experiment with different pricing packages - fixing prices for one or two years, offering discounts to attract new customers and so on. And transparent pricing facilitates tacit collusion, as discussed separately.

Be that as it may, when the Government announced in April 2012 "how the Government and energy suppliers will put people in control of their energy bills by making sure that they can easily find and get the best deal for them". This, however, amounted to no more than suppliers agreeing to draw customers' attention to their own best deals, rather than those offered by competitors. And it certainly did nothing to address the problem of tacit coordination.

Prime Minister David Cameron went a lot further in October 2012 when announced that "we will be legislating so that energy companies have to give the lowest tariff to their customers". The Prime Minister was probably trying to deflect political criticism in advance of the publication of the Energy Bill, recognising that the policies in the Bill would inevitably drive energy prices even higher. But his intervention was met with surprise and some ridicule, especially as Ofgem were dumping non-discrimination clauses.

Then, only two days later, Ofgem announced a further round of consultation as part of its Retail Markets Review, in October 2012. They suggested a more complex package than that suggested by the Prime Minister:

- A ban on complex multi-tier tariffs and the scrapping of uncompetitive dead tariffs

- All tariffs to be shown as a standing charge and single unit price

- A limit on number of core tariffs each supplier is allowed to offer

- All consumers to be told their supplier's cheapest tariff on their bill

- A Tariff Comparison Rate to compare tariffs 'like for like' across the market

- New personalised information to help consumers find their best deal

- Fair treatment to be enforced by standards of conduct backed by fines

- Consumers to default to cheapest tariffs at the end of fixed term contracts

This package was superficially attractive in that it aided price comparison without appearing to limit the scope for competition - but it would still encourage all the companies to track each other's prices much more closely than in the past, thus aiding tacit collusion and so possibly increasing prices across the board. UEA's Catherine Waddams explained the problem very clearly: Sounds like a great idea until you think how the companies will react. If everyone is on the cheapest tariff, there is only one tariff - but it is unlikely to be the lowest price they offer now. In common with many other products and services (think of telecoms) many of the cheaper tariffs are to tempt householders to change supplier - which is at the heart of a competitive market. Since any offer which a company made to try and encourage switching would oblige them to lower all the charges they make to their established customers, we would not expect to see very many offers. The government and the regulator are keen to encourage new entrants into this industry. A small new competitor, with perhaps 100,000 consumers (less than half a percent of the market), would face a cost of £2million from lost revenue with existing accounts if it offered a twenty pound discount to attract new customers.

As the Prime Ministers' intervention faded into history, Ofgem's proposals came into effect on 1 January 2014. From that date, suppliers could only offer a maximum of four tariffs per fuel type, one of which will be a variable price alongside some fixed price deals. And all tariffs will follow the same structure - a starting charge (which may be zero) and a unit rate. Complex tiered rates (which rise or fall with increased consumption) are no longer allowed.

Further discussion of switching rates then formed a significant part of the CMA's Market Investigation.

Consumers' reluctance to switch suppliers is also discussed here.

Labour's Price Freeze Proposal

Constantly rising prices were by 2013 causing desperately serious problems for the poorer in our society. There was therefore much to applaud in Labour Opposition Leader Ed Miliband's announcement in September 2013 that Labour would (if elected in May 2015) take quite dramatic steps to inject competition into the energy market. The large energy companies had lost most of their friends as a result of a long history of mis-selling; indeed, Scottish Power were fined £8.5m only two or three weeks after Mr Miliband's speech, and all companies' profits had been rising, albeit from a low base. Labour accordingly announced a 10 point energy plan in which they, inter alia, pledged to

- force the separation of the generation and supply arms of the major companies,

- introduce an open pool in the wholesale electricity market, and

- abolish Ofgem and 'create a tough new energy watchdog'

These policies were unfortunately to be introduced without the assistance of a full market investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the successor to the Competition Commission. This reference was long overdue and it was a shame that Labour did not promise such an investigation, leaving the door open for an earlier reference to the CMA by the current coalition government or by Ofgem itself - as indeed happened a few months later.

But experts were much more concerned about Mr Miliband's accompanying announcement that his government would legislate to impose a price freeze between the election and the end of 2016, followed by a warning next morning (according to the BBC) that 'without changes, [current] taxpayer-funded guarantees to energy firms might not be sustainable'. This caused neutral commentators, as well as the industry, to ask some interesting questions such as:

- Won't this encourage the industry to increase its (currently deregulated, and supposedly market-driven) prices before the election, or strongly deter the industry from reducing its prices (if it were able to), during that same period?

- What would happen if world energy prices rise sharply between 2015 and 2017? It is possible to imagine scenarios in which falling profits in the period to 2015 are then wiped out by subsequent rises in world energy costs. Would Labour let the industry incur large losses or would it (and in what circumstances would it?) step in to help? These questions became even more interesting following the very sharp falls in world energy prices in late 2014 and early 2015, which could presumably be rapidly reversed.

- Won't the proposed freeze, and the warning about unsustainable taxpayer guarantees, send a strong message to the Boards of the energy companies that new investment might not be profitable, and so should not be made, so imperiling both the security of energy supply (leading to blackouts) and green investment? (One city analyst (Liberum Capital) claimed that Labour's announcement had "killed stone dead" any chance of one of the big six energy firms obtaining finance for a large new wind farm or power station.)

- More generally, doesn't the imposition of a price freeze by Ministers set a very worrying precedent? It is one thing to refer an industry to the competition authorities; that is what they are there for. But a vote driven price freeze is a much bigger step in legal and constitutional terms. Indeed, one wonders if it would survive legal challenge.

It didn't help that, in the morning after his announcement, Mr Miliband did not have good answers to these questions, saying only that "[the sharp rise in world energy prices] is not going to happen", and (if profits do rise before 2015) "we will cross that bridge when we come to it". It became all too clear that Labour had generated a slogan, not a policy. (And the Ukraine crisis in 2014 was a good example of the sort of event that can disrupt energy supplies, and so sharply increase energy prices.)

And then, as time ticked by, commentators increasingly drew attention to concerns about political interference in the regulatory process. As UEA's Chris Henretty pointed out in a blog: "Abolishing regulators and establishing new regulators to carry out the same functions is problematic, because it undermines the reasons that these regulators were set up in the first place. .. regulatory authorities are the answer to [the] problem of credibly committing to policies given the electoral incentives they face. When elections are far off, or when the issue of the cost of living is low on the agenda, governments may wish to encourage companies to invest. But companies may refrain from investing if they believe that the government will change its mind later on when elections draw closer, or when the issue of the cost of living becomes more salient. As a response to this, governments set up regulators which absolve them of responsibility for regulating. It's the Look Ma, No Hands! approach to utilities markets. [But] What happens when you promise to abolish regulators? The problem of credible commitments rises its ugly head again. Companies may refrain from investing either because they fear that if the regulator allows them to raise prices in order to fund investment, the regulatory regime will simply be altered, or because they believe that the regulator will pull its punches in order to avoid being shut down and reformed."

Cynics also noted that the big energy companies all announced large price rises (around 10%) in the weeks following Mr Miliband's announcement of a subsequent price freeze. Most, if not all of the increases would have been announced anyway but they certainly made sense (from the companies' point of view) given the possibility that price increases may not be possible after 2015.

But Labour's announcement appeared to resonate well with a public very worried about the cost of living. And, in Scotland, the ruling Scottish Nationalist Party trumped it in October 2013 with an announcement that they would cut energy bills by 5% a year if the country voted for independence in the forthcoming referendum. This would be achieved by removing environmental and social costs from energy bills and funding them out of taxation.

The Coalition Government in London did no more, at first, than to ..

- say that they would continue to encourage switching (see above)

- note that they were "negotiating an agreement with the major energy suppliers to help consumers find the best tariff", and

- proceed with provisions in the Energy Bill that would set a limit on the number of energy tariffs offered to domestic consumers; require the automatic move of customers from poor value closed tariffs to cheaper deals; and

require the provision of information by suppliers to consumers on the best alternative deals available to them from them

.. all of which fell somewhat (but sensibly) short of the Prime Minister's announcement a short while earlier that they would force energy companies to offer everyone their lowest tariff.

But it didn't take long before the Prime Minister decided to promise "an annual review of competition in the market" and to "roll back some of the green regulations and charges that are pushing up bills". CCP/UEA's Catherine Waddams commented perceptively:

First the good news: at last someone is suggesting that the competition authorities who have expertise in such enquiries should be the ones to decide whether there are competition issues in the energy market, or whether the rising prices are, as the companies claim, a result of rising world energy costs. This isn't easy to disentangle in a sector with very volatile upstream costs, so it needs experts to examine the situation thoroughly to identify whether there are problems which mean this market isn't working well. The Office of Fair Trading and the Competition Commission (from April their combined forces in the new Competition and Markets Authority) are best positioned to come up with an answer which carefully considers the issues rather than responds emotionally with a short term suggestion to the challenges of rising energy prices. Research at CCP has confirmed that short term interventions, such as the non discrimination clauses, had the effect of reducing switching and driving up prices, rather than lowering them as had been intended. It is crucial to investigate whether there are underlying problems in the market, rather than provide a series of sticking plasters for the symptoms as they appear.

The bad news is that it is highly unusual and a matter of some concern that the government is deciding on which markets should be referred for such an enquiry. Many have called for such a referral over the past many years, and it would be good if such an inquiry had been started in the past, so we don't have to wait now for the results. But it is very dangerous if governments decide which markets should be investigated. One of the great benefits and strengths of the UK competition regime is that it is independent of political parties which, as we have seen, have tended to provide short term solutions which often cause more problems than they solve. One reason this is important is that the companies have security against government interference so they can raise capital with lower risk and cost to consumers. If lenders expect the companies to be subject to repeated government intervention it will be consumers who pay for this in the long run.

And the ugly part of the announcement is the removal of environmental taxes. If we are to move to a low carbon economy as the British government has pledged, we need to confront the need for us all to recognise the cost to the environment of using carbon generated fuels. This raises the cost of energy, and discourages us from using it Ð and that is exactly the point. For those who cannot afford the increase because of low incomes, it is important to provide additional income and ensure they do not suffer additional hardship, but reducing the price of their energy does not give them (or others) the necessary messages about the damage that carbon burning imposes. We need to be clear about prices reflecting appropriate costs, and ensure that the additional revenue raised is used to compensate those who struggle because they are on low incomes Ð and so we can have a virtuous tax.

Professor Waddams' intervention was quickly supported by ex-OFT Chief Exec John Fingleton, writing in the FT, who argued strongly that the energy market should be referred to the Competition Commission. And then the Energy Select Committee called the industry and Ofgem before it in an attempt to understand what was driving the price rises. In practice, of course, the exchanges shed very little light on what is a very complex area, with the 'Big 6' arguing that they had to raise prices at least in part because of forthcoming increases in their own input prices, whilst their (very much) smaller competitors said this was nonsense. E.ON even announced that they had written to the Prime Minister recommending a Competition Commission inquiry!

Ofgem didn't help by announcing that wholesale energy prices had in fact hardly risen at all over the last year - and then putting out this statement on the morning of the committee hearing:

"Our own weekly monitoring .. estimates that, over the last year, the cost of wholesale gas and electricity to serve a typical dual fuel customer would have risen by around £10 to £610. However, this figure could be higher depending on the hedging strategy of an individual company for buying gas and power in forward markets. We have also published actual market data which shows that the wholesale price of gas for use this winter is 8 per cent higher than the price of gas for use last winter. The wholesale price of electricity for use this winter is also 13 per cent higher than the price of electricity for use last winter."

This left this writer, for one, totally confused. (But see Note 1 below for further information about the 8/13% figures.)

Former Prime Minister Sir John Major intervened in the debate towards the end of October 2013 when he suggested that a one-off windfall tax would be an appropriate response to rising energy prices. The Government then published its Annual Energy Statement on 31 October 2013. This included:

- a promise to press the industry to switch customers within 24 hours, rather than the previous several weeks,

- the introduction of annual reviews of the state of competition in the energy markets to be undertaken by Ofgem working closely with the Competition and Markets Authority, when it comes into being, and

- consultation on the introduction of criminal sanctions for anyone found manipulating energy markets and harming the consumer interest.

The first announcement was to be welcomed, but the second less so as an annual assessment (even if supported by CMA expertise) would be much less penetrating than a full-scale Market Investigation, and could not trigger the CMA's strong remedies powers. It was far from clear what the third announcement meant. Cartels and much other overt market manipulation were already illegal. Tacit cooperation - possibly a significant problem in this industry - is commonplace in many other industries and could not sensibly be classified as market manipulation.

A couple of weeks later EDF announced that it would increase its prices by only 3.9% - but on the assumption that the Government would fulfil its commitment to "roll back some of the green regulations and charges that are pushing up bills", thus neatly ratcheting up the political pressure on the Government to reduce energy bills and increase general taxation. Npower weighed in support by promising that it would cut its planned rise in its average gas and electricity energy bill to from 10.4% to 6% if the government reduced the green levies.

SSE, on the other hand, reported a 12% drop in recent profits caused (they claimed) by a loss replacing a profit in their customer-facing supply business, caused in turn by higher wholesale energy costs and rising green/social levies. More ominously, it forecast reduced investment spending until the political and regulatory environment became less risky.

The Government responded to this severe pressure by announcing a delay to 2017 in implementing one of the 'green taxes' - the Energy Companies Obligation [to help certain home-owners save energy by installing insulation and new boilers, with the cost being passed on to all customers via higher bills]. Ministers trumpeted that this would cut average bills by £50pa, but were less keen to point out that c.600,000 customers would have to wait for up to two years longer to save an average of £400pa on the energy bills. The insulators' trade association estimated that energy companies would earn £360m in extra fuel sales because of the delay.

And then, in March 2014, the Energy Secretary at last made it clear that he would welcome a Market Investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority. This followed much previous discussion and inaction, summarised in Note 3 below. Click here to read what happened next.

Note 1

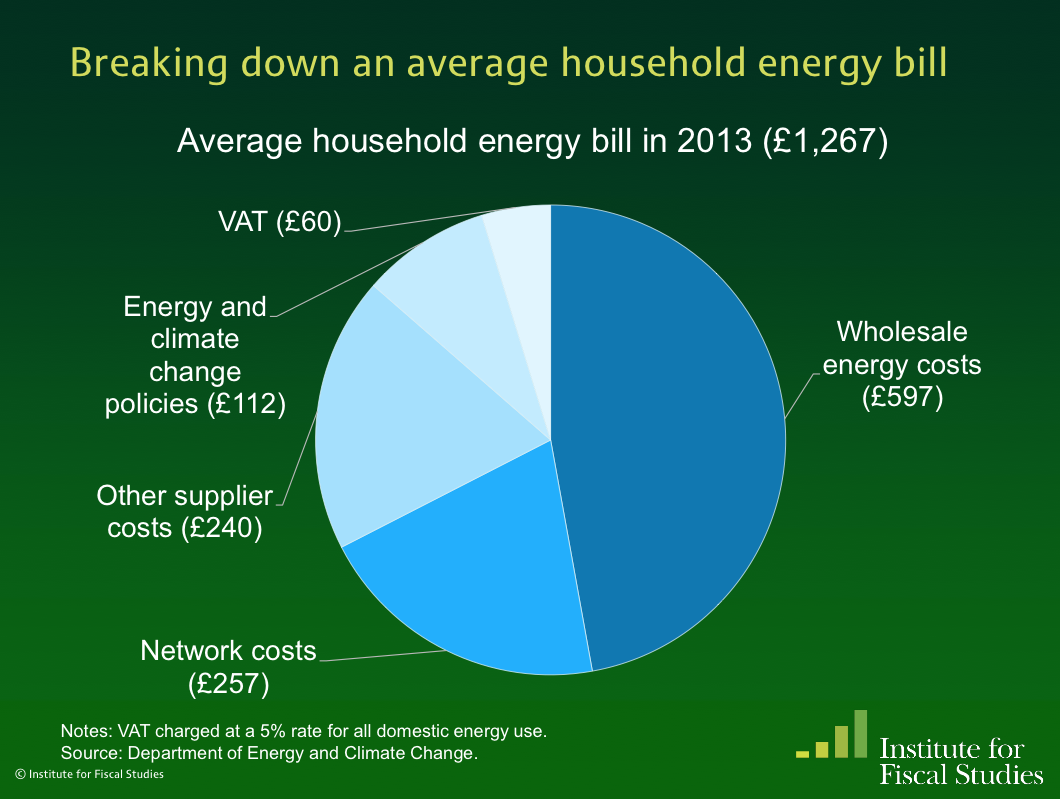

Ofgem published the following figures in October 2013. A typical dual fuel bill can be analysed as follows:

- Wholesale costs, up 140% (electricity) and 240% (gas) since 2003, and 13%/8% higher respectively in the last year: 46%

- Network costs (the cost of delivering energy through pipes and wires, set by Ofgem) 23% (These fell 50% as a result of tough regulation in the 15 years following privatisation. They had recently increased in order to fund new networks to help connect low carbon energy, and replace ageing pipes and wires. But no further real terms increases were expected over the next few years.

- Environmental & Social costs, (set by the government and Ofgem), 10x higher than in 2003 8%

- VAT, charged at a flat rate of 5% so the tax take increases every time underlying costs and prices rise: 5%

- Supplier costs 13%

- Supplier profit 5%

Note 2

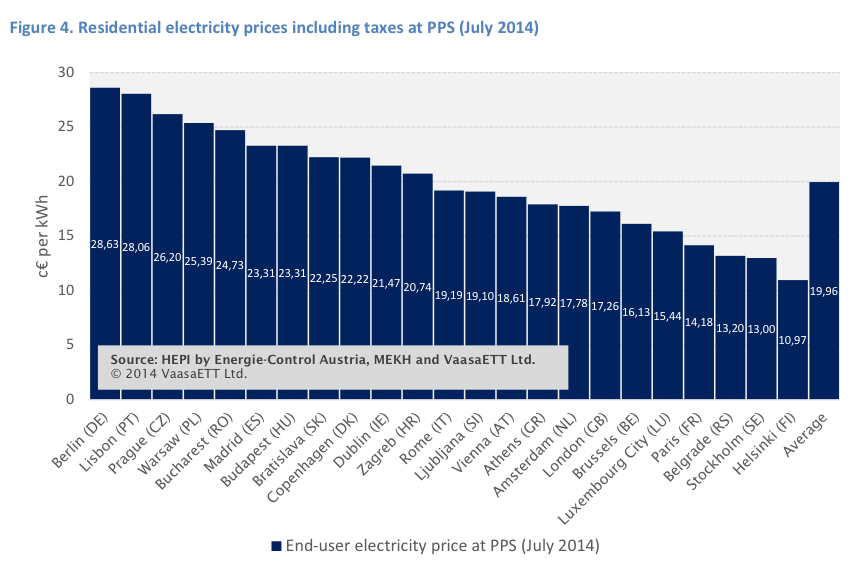

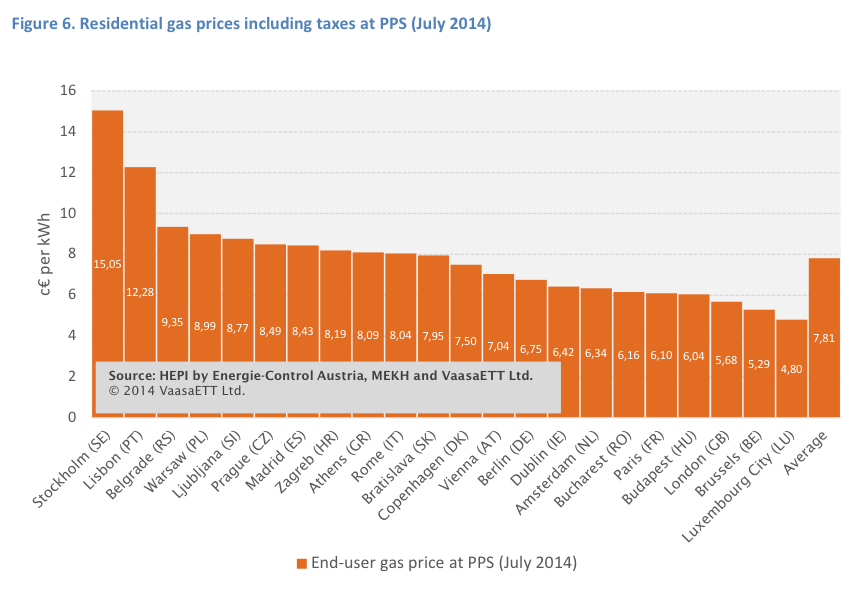

The Institute for Fiscal Studies published this first diagram containing similar figures, in December 2013. But the second and third diagrams show that UK energy prices were far from the highest in Europe. (Prices are shown on a Purchasing Power Standards basis which strips out the impact of exchange rates, giving a better comparison of prices.)

Note 3

This note summarises some of the discussion etc. which lay behind Ofgem's failure to refer the energy market for investigation by the Competition Commission.

The charts on this web page summarise cost pressures and prices up to 2013. The most significant upward pressure seems to have come from the imposed cost of investing in infrastructure (to improve security of supply) and 'green energies'. But there is also clear evidence of substantially increased profits, albeit from low levels. Ofgem had accordingly taken several looks at the energy market following which all of which they announced that they had found no evidence of anti-competitive behaviour. In practice, this meant that they had found no evidence of illegal price-fixing (which few had suspected anyway - but see further below) but they did not have the information-gathering powers and/or resources to carry out the rather more detailed investigation which might have found evidence of tacit collusion. The Competition Commission (CC) could, for instance, have discovered much more about the supposedly inflexible and/or expensive long-term overseas contracts through which gas was purchased. The obvious answer was to refer the market for investigation by the CC but, like most utility regulators, Ofgem were decidedly and persistently reluctant to do so.

Critics therefore continued to complain about Ofgem's inaction, until the regulator announced another probe beginning in November 2010, having noted sharp increases in retail profit margins and having gained access (via changed licence conditions) to more detailed company accounting information. But (unlike the CC) the regulator still could not find out what the companies pay for their imported gas, which rather hampers any serious investigation. (Many suppliers pay for their gas through long term contracts in which prices are linked to the cost of oil. An effective market might encourage competition from companies which had not entered into such contracts.) Despite this, there was no mention in Ofgem's press statement of a possible CC reference, nor to the fact that the CC already had much stronger information gathering powers and could have carried out a deeper investigation two (or four, or six) years previously.

Ofgem announced the result of its probe in June 2011, noting that "Our latest report on prices also gives even more impetus to the need for radical reform as it shows that turmoil in global energy markets during 2011 has pushed up wholesale costs by 30 per cent since December 2010. Now more than ever, consumers need to have confidence that competition can operate effectively in setting energy prices." Despite this, the regulator merely announced moves which would "sweep away complex tariffs" and "encourage more firms ... to enter the energy market and increase the competitive pressure on the Big Six." It remained to be seen whether Ofgem was to be shown to have been over-confident in their ability to promote effective competition, but it did still seem disappointing that they again declined to take advantage of the potential power of a reference to the CC.

There was an interesting development in November 2012 when a whistle-blower accused the energy companies of manipulating wholesale gas prices, rather in the way that some banks had manipulated LIBOR. This was a serious accusation, though not quite the same as cartel-like price fixing. And it is not yet clear whether this alleged manipulation of wholesale prices led to an increase in retail prices.

It was interesting, too, that allegations surfaced in February 2013 that the UK had been exporting gas for lower prices than it had simultaneously being importing it (in liquefied form) for example from Qatar.

And then, in June 2013, Ofgem announced that it would encourage competition - and hence lower prices - by requiring the big six energy suppliers to sell power to their smaller competitors at prices set up to two years in advance. This should lead to prices being a little less than they would otherwise be, although the government's wider energy policies will mean that prices will still continue to rise for the reasons summarised above.

Ofgem's Ian Marlee, appearing on the Today Programme on 2 January 2013, agreed that there was not enough transparency in the wholesale energy market but hoped that the situation would improve when, later in the year, certain reforms would add 'depth' to the market and make it easier for independents to buy wholesale energy. It remained to be seen whether this would make it any easier to identify the combined wholesale/generation and retail profits of the Big Six.