Market definition is probably the most entertaining activity for competition practitioners, because (a) it is important, and (b) anyone can have a view, and no one view is ever obviously correct.

It is important because regulators are worried that companies may monopolise - or get close to monopolising - a market, and monopolies are bad for all sorts of reasons explained elsewhere in this website. So regulators are very interested in market share and market power.

But what do we mean by "a market"?

- Would it matter if I were to monopolise the sale of English Discovery eating apples? Probably not. They don't sell well anyway and, if I tried to impose as significant price rise, customers would simply buy other apples.

- What about the much more popular English Gala apples. More worrying, but not worrying enough?

- All English apples? - definitely a stronger case. I reckon I could start charging premium prices if no-one could buy English apples anywhere else in the UK. But if the competition authority came after me, I would ask my lawyers and economists to argue that my customers would readily start buying foreign apples if my prices went up. So my various mergers might be allowed.

- All apples?

- All fruit?

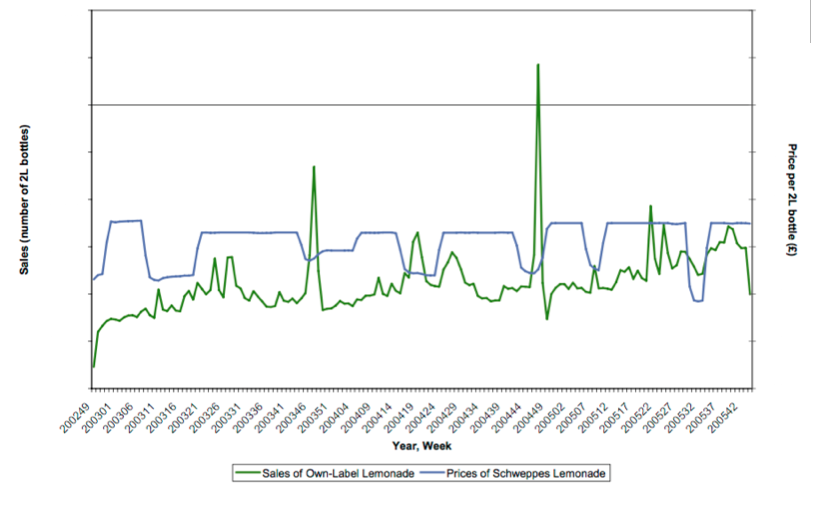

In practice, therefore, lawyers and economists argue about market definition by deploying a mixture of thought experiment - as in the apple case above - and econometric analysis. In other words, they look for data that shows what actually happens to sales when prices rise. This chart is a good example. It shows that the sales of an own-label lemonade (maybe Sainsbury's or another supermarket) did not increase in response to increases in the price of a popular branded lemonade such as Schweppes. This was one piece of evidence that persuaded the Competition Commission that own-label fizzy drinks were in a monopolisable market separate from branded drinks. They were therefore concerned about a merger which brought together two big manufacturers of non-branded drinks.

But what about those two peaks when non-branded sales rose spectacularly? Answer - it was Christmas 2003 and 2004.

Having said all this, there are cases in which market definition might complicate rather than simplify the analysis of the effect of a merger on competition. In these cases it might be appropriate to go straight to analysing the effects of the merger.

Want to learn more? I recommend pp4- of Paul Geroski's Essays in Competition Policy and John Davies' Market Definition Guidelines.