Overview

The health service in the UK is mainly organised by the government but provided by the private sector in the form of self-employed GPs, dentists etc, plus hospitals with a great degree of independence and which compete with each other. The sector is subject to a great deal of regulation including competition law which can lead to the competition authorities making decisions which conflict with government policy - for instance to merge hospitals.

Education in the UK is also mainly organised by the government but provided by a wide range of schools, colleges and universities including semi-independent academies. There is also a significant wholly independent private sector.

The following notes explain why it is extraordinarily difficult to regulate these two sectors.

For a start, they both contain near-monopolies. The health service is (quite rightly) staffed by restricted-entry professionals, whilst specialist hospital services need to be provided in a small number of regional centres so as to concentrate relatively small patient volumes and specialist clinical expertise. And most of us are reluctant and/or unable to change general practitioners (GPs). Similarly, many and maybe most of us cannot choose where to educate our children. Schools need to be nearby, or easily accessed via public transport, and popular schools are very often heavily over-subscribed and so unavailable to parents who do not live very close by.

As a result, the quality of the service provision of both sectors is often the subject of serious criticism. They are both heavily taxpayer funded. Successive governments have therefore been very keen to find ways of introducing competition into the sectors, so as to drive greater efficiency and improved service quality.

I rather like Professor Rudolf Kleon's description of the NHS as a restaurant where one person orders the food, another one eats it, and someone else again pays the bill.

However, even putting their monopolistic characteristics on one side, it is clearly impossible to abolish subsidies and introduce unrestricted competition into either sector. This would inevitably price-out poorer members of the community, imposing unacceptable social cost

There is also the point that effective regulation in any sector has to ensure that price competition does not leak through into unacceptably reduced service quality and/or a reduced range of services. But this is extremely hard to do in these sectors, for what is 'unacceptable'? In health, it is surely near-impossible to measure 'quality', let alone ascertain what trade-offs would be acceptable.

Another problem is that identifying poorly performing schools and hospitals can perpetuate the problems as staff become demoralised, recruitment becomes more difficult, and kids stop trying as they see themselves or their communities as failures.

The threatened closure of a poorly performing school, university or hospital is usually strongly opposed by its local community. And actual closure can seriously damage the health or education of the patients or pupils who are present whilst the closure is taking place. In practice, therefore, closures are generally avoided by appointing administrators tasked with turning the institution around.

Here are some of the more detailed issues that arise, beginning with ...

Health Regulation

Choice & Competition

Successive UK governments have stressed the importance of choice and competition in health services, so that patients can in effect drive up standards. But it is worth noting that the biggest gain from, for instance, getting surgeons to publish their success rates seems to have been that this encouraged them to learn from one another. Good practice and promising new techniques accordingly spread much more quickly than in the past. The result was that all surgeons' performance came up to near the standard of the best, and patients did not need to 'exercise choice' even though that was the original headline reason for the publication of the data.

Successive UK governments have stressed the importance of choice and competition in health services, so that patients can in effect drive up standards. But it is worth noting that the biggest gain from, for instance, getting surgeons to publish their success rates seems to have been that this encouraged them to learn from one another. Good practice and promising new techniques accordingly spread much more quickly than in the past. The result was that all surgeons' performance came up to near the standard of the best, and patients did not need to 'exercise choice' even though that was the original headline reason for the publication of the data.

There has always been significant private sector health provision in the UK. To begin with, all GPs are self-employed, although their income is to some extent set by the Government, depending on the number of patients they can attract. And many consultants have a significant private practice delivered through their own consulting rooms, private hospitals and private wings within NHS hospitals. More recently, successive governments have encouraged NHS hospitals to become more self governing and competitive, beginning with the creation of Foundation Trusts in 2002, regulated mainly by Monitor with the initially separate Cooperation and Competition Panel ensuring fair play on the economic/competition front, whilst the Care Quality Commission and all the Professional Bodies monitored the quality of care provided by doctors, nurses and other professional staff. It may or may not have helped that the Cooperation and Competition Panel was in due course subsumed into Monitor.

The post-2010 Coalition Government extended Foundation status to all hospitals, and abolished Strategic Health Authorities and Primary Care Trusts: the organisations previously charged with coordinating NHS services in their areas. Clinical Commissioning Groups, which are overseen by local GPs, are now responsible for buying services from a range of `NHS and private providers of of NHS services. However, the key features of (a) patient choice of NHS hospital and (b) a centrally set tariff that is paid to hospitals for treating patients were established by the previous Labour Government. The intention is thus that hospitals should compete for patient referrals from GPS and be rewarded for attracting and treating each additional patient.

Hospital Mergers

Ministers and NHS managers were no doubt surprised and annoyed to find that they could not merge (combine the finances and management of) hospitals and other trusts without getting permission from the competition authorities who would want to be assured that doctors and their patients would still be able to choose between competing health service providers.

But there was an interesting breakthrough in August 2017 when the Competition and Markets Authority allowed the merger of two Manchester hospital trusts (which managed 9 hospitals between them) - even though they forecast that there would be a significant lessening of competition. The CMA did this because it decided that "the merger will give rise to substantial benefits for the care of patients. These outweigh any harm caused by a loss of competition between the merging trusts. The benefits include reductions in patient mortality, clinical complications and infection rates."

This decision was particularly noteworthy because competition authorities are always extremely reluctant to accept that such 'customer benefits' will outweigh the dis-benefits arising from reduced competition. Indeed, this was probably the first time that the UK authorities accepted such an argument in over 20 years.

But then ...! The CMA published a working paper suggesting that hospital mergers tended to lead to increased patient harm from falls, pressure ulcers, blood clots and urinary tract infections. And Chicago's Stigler Centre subsequently reported an increase in certain mortality rates after mergers between competing hospitals in the USA.

So What About Quality?

As noted in the introduction, there is a huge danger that price competition can lead to providers cutting corners (or worse) when considering the quality, range and service aspects of their offering. This needs to be controlled by sensible regulation but the UK regulatory regime has suffered some serious failures, most obviously at Mid-Staffs and Morecambe Bay.

Blogger Guido Fawkes was not impressed by what he saw as a regulatory quagmire, nor the October 2013 Chair-designate of Monitor:-

"It's hard to summon the invective to describe the nice young regulator who's going to head up the NHS's Monitor. Pleasant, modest Dominic Dunn (£63,000 a year for three days a week) is there to provide another layer of strategic obfuscation in the multi-billion miasma of the NHS. That's not written in to his job description but he is certainly an elusive target. When asked a direct question - is it your job to promote competition in the NHS? - he answered: "Not to promote competition, but to address anti-competitive behaviour." Or again: "We don't have enough radiotherapy in my part of the country. Is it your job to address that lack?" He said: "I certainly agree with avoiding the situation where there is enforcement action needed." When the revolution comes, these people will be carrying bedpans.

[Parliamentary committee Chairman] Stephen Dorrell asked Mr Dunn what he'd like to be remembered for after a decade running the joint. "Well, er I this it's knowing how you define success." Oh yes. Defining success, that's the key to it. These people do what they do and call it success. But judging from the administrative esperanto he spoke, success won't be getting nurses to wash their hands. It won't be stopping staff telling old people to "go in their beds" instead of taking them to the toilet. Success won't be rooting out hospital heads responsible for deaths by incompetence, negligence and sadistically indifferent staff. No, success will be aligning the strategic priorities and navigating the transitional issues between national integration and intrasectoral competition.

Bruce Newsome, too, writing in 2017, thought that the NHS was accountable to too many independent regulators, and that it was about time that the Secretary of State for Health, and his officials, began to take responsibility for the NHS' many failings. Click here to read his article.

Complaints about the quality of NHS health care continued. The Times, for instance, reported in August 2017 that 'NHS abuse of mental patients [is] endemic'. The underlying problem was undoubtedly grossly inadequate resources deployed by often ineffective managers. But regulators were clearly unable to make much impact given that the situation would hardly be improved if large financial penalties were imposed or poorly performing facilities were closed.

Pharmaceuticals

The availability of (usually free to patients) of health treatments is controlled by NICE - the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (The need for this independent regulator is discussed here - as are attacks upon its independence)

Even so, there was an interesting report, in February 2015, of a York University-led study which suggested that (albeit in response to patient pressure) the cost of newly regulator-approved and often very expensive drugs was literally killing other patients as NHS resources were diverted away from areas such as radiotherapy, nursing and mental health. According to a Times report of the study, "Approving a drug that costs the health service £10 million will lead to 51 extra deaths elsewhere as well as worse quality of life for many other patients." And "The Cancer Drugs Fund costs other patients five years of good quality life for every one year it adds."

There has only been one recent political interference in the regulatory process when the Conservatives promised to set up a Cancer Drugs Fund during the 2010 election campaign amid concern patients were not always getting access to the latest drugs. But a 2017 academic report found that the fund in England had been a "huge waste of money" and may have caused patients to suffer unnecessarily from the side effects of the drugs. Nearly 100,000 patients received drugs under the scheme which ran from 2010 to 2016 and cost £1.27bn but researchers found only one in five of the treatments was of benefit.

International Comparisons

As an aside, we all know that the provision of health care in the USA is the subject of even more highly charged political debate than in the UK, although it too is provided by a complex mixture of publicly and privately funded organisations. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) came into effect in October 2013 and aims to cover 32m uninsured people and ensure coverage of those with pre-existing conditions. From a competition economist's point of view, it should improve labour market flexibility. Previously, most working people got insurance through their employers and this complicates decisions about leaving a job, particularly for people with long-lasting medical conditions. One commentator called it a form of serfdom.

At the macro level, too, the US health system is very inefficient compared with those of other large high-income countries. The US spends 18% of its gross domestic product on health against 12% in the next highest spender, France. Even the publicly-funded US health sector spends a higher share of GDP than those of Italy, the UK, Japan and Canada, though many people are left uncovered. US spending per head is almost 100% more than in Canada and 150% more than in the UK. In return for this massive spending, life expectancy at birth is the lowest of these countries, while infant mortality is the highest. Potential years of life lost by people under the age of 70 are also far higher, for both men and women.

Germany is interesting, too. The FT's Lucy Kellaway has pointed out that the Germans each year throw 217m sickies as a result of musculoskeletal disorders (which mainly means backache). In the UK the figure is 35m days, while in Greece it is only 1m. The cause is no doubt a thriving German GP-fed back therapy industry, including (according to Lucy K) vendors of volcanic mud. But there is not much that any regulator can do to overcome what seems to be a deep-seated national obsession, which certainly doesn't seem to harm the German economy, which is in much better shape than the Greeks'.

Note

I am grateful to Andrew Taylor of Aldwych Partners for contributing to, and correcting earlier versions of, this web page.

Now let's look at ...

Higher Education

Approaching 50% of young people now begin a university course, and often pay (or borrow) approaching £20,000 a year to do so, including tuition fees, accommodation, and living and other expenses. But:

- Undergraduates are often surprised by their limited amount of 'contact time' with their supposed teachers.

- (One student told me that her Russell Group university scheduled only one lecture, and a week of exams, in the third term (semester) of her first year there - presumably because the academics wanted to focus on research.)

- Students are also often surprised by large size of tutorial groups and therefore by the lack of personal attention from their tutors.

- At least one university now no longer relies on tutors to monitor students' engagement with courses, but instead monitors library use, lecture attendance etc. and then 'nudges' any student whose interest seems to be fading. Not very caring, when you think about it - but dead cheap!

- The tutors themselves may be relatively post-grads, insufficiently experienced to provide pastoral care or other advice to their students.

- The proportion of (supposed) first class degrees increased from16% to 27% over the six years to 2017.

- Even the government, in a 2020 report, accepted that the annual National Student Survey had since 2005 'exerted downward pressure on standards [because] good scores are most easily achieved through dumbing down and spoon-feeding students'. Students who choose courses having been guided by the NSS tend 'to choose courses that are easy and entertaining, rather than robust and rigorous'.

There is therefore increasing interest in the quality of tuition and other aspects of university life, and this has led to greater regulatory intervention. But it's a tricky area to regulate, given the importance of academic freedom, and the reluctance of students and academics to criticise their institution given the importance to their CV of their having been seen to attend and/or work at a prestigious body. It was therefore good to see the National Audit Office taking an interest in this area in a report published in late 2017. The NAO noted that

"Only 32% of higher education students consider their course offers value for money, and competition between providers to drive improvements on price and quality has yet to prove effective ... “We are deliberately thinking of higher education as a market, and as a market, it has a number of points of failure. Young people are taking out substantial loans to pay for courses without much effective help and advice, and the institutions concerned are under very little competitive pressure to provide best value. If this was a regulated financial market we would be raising the question of mis-selling."

The Office for Students

The OfS became operational in April 2018, bringing together many of the functions of the Higher Education Funding Council, the Office for Fair Access (see below), the Department for Education and the Privy Council together into a single organisation, 'putting students at the heart of the market'. It will be responsible for the ...

Teaching Excellence Framework

There is commendable interest in improving the quality of undergraduate teaching given the problems summarised in the introductory paragraph to this web page. So universities are now assessed via the TEF on the quality of their teaching.

Professor David Weitzman provided some interesting background to this exercise, writing in 2017:

" ...we’ve been here before. Despite a range of processes to monitor educational quality, we have failed to crack the problem. We have monitored, reported and walked away, hoping that any quality improvement would persist. In the 1990s a system was introduced for evaluating the quality of teaching and learning in every subject at every university. It was probing, thorough and potentially valuable, but academics disliked it. Yielding to pressure, the monitoring body abandoned classroom observation and, later, all monitoring.

Quality is maintained only by maintaining monitoring. Improvements in quality merit lighter-touch monitoring for sustainability, and the interaction between teaching staff and their academic monitors can provide a healthy, two-way exchange of experience and good practice."

Some of the 2017 TEF assessments were controversial, apart possibly from the most surprising, the Bronze (lowest level) of award given to the London School of Economics:

- “The LSE falls down on pretty much every important TEF measure. They are both objectively poor and well below their benchmark on measures like academic support, assessment and feedback,”

- “While lower awards given to other prestigious universities are perhaps more questionable, the LSE really is a slam-dunk case of bronze, and this appears to back up the intention of the government’s new rating process.”

- "For (LSE) students it came as no surprise. While most feel privileged to be studying at such an illustrious institution, they are frustrated at the inaccessibility of many academics, scant feedback, constant sabbaticals and classes routinely covered by PhD students."

- “The LSE is a research business with a degree factory on the side. Undergraduates are the poor relations here,” one politics student said.

- "Undergraduates have no right to feedback after exams and have to use a booking service for appointments with tutors. “I struggle to get a single line of feedback sometimes, and then when I get it I need to ask a follow-up question and it all starts again,” the (LSE) politics student said."

- "When (LSE) PhD students cover the classes for the regular academics, it can come as a relief. “I spent many lectures listening to famous academics recount anecdotes from their personal lives, entertaining but totally irrelevant to the topic. On some occasions I can’t understand anything because their English is so poor,” a history undergraduate said.

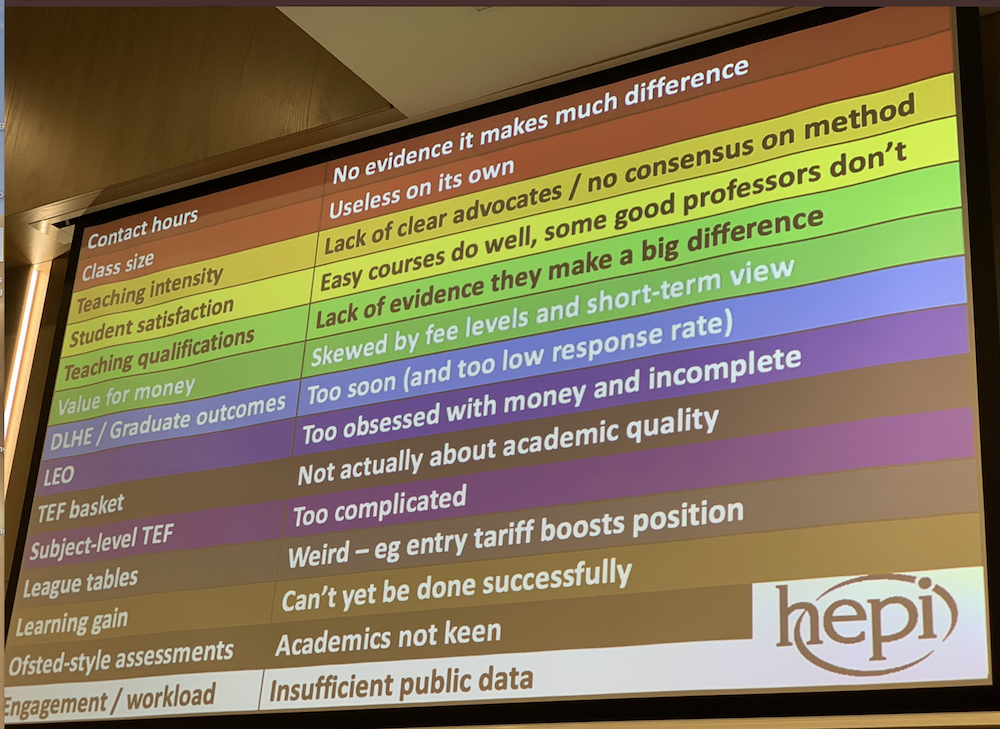

But - commenting more generally on the TEF - some commentators recommended caution:

Dylan Wiliam:- "We do need to be concerned about the quality of teaching in our colleges and universities, but the results of the second round of the Teaching Excellence Framework add little to our understanding of the quality of teaching in our higher education institutions (“Elite universities exposed as second-rate”, June 22). Student satisfaction surveys are notoriously inaccurate as indications of the quality of teaching they have received — many studies show students prefer styles of teaching that significantly reduce how much they actually learn — and the TEF provides no data about whether students are in fact learning anything. Moreover, good postgraduate employment statistics do not take into account whether students are actually using anything they have learnt during their studies, or whether they have the flexibility to adapt to the changing world of work. Perhaps most worryingly, the Higher Education Funding Council for England is actively inviting simplistic and meaningless comparisons by presenting complex, multi-dimensional data in terms of gold, silver and bronze awards. The TEF may raise the issue of teaching quality in universities, but as it stands will do little to improve it."

I suspect that this slide summarises the problem very well:-

Access

The Office for Fair Access (OFFA) seeks to ensure 'that everyone with the potential and ambition to succeed in higher education [has] equal opportunity to do so, whatever their income or background'. They accordingly aim to make sure that higher education establishments have measures in place to attract and support disadvantaged students.

Research

Until the arrival of the TEF (see above), universities' reputations hung mainly on the Research Excellence Framework (REF) and its predecessor the Research Assessment Exercise. They seem to have provided a reasonable rough-and-ready assessment of the strength of a university's research but had two key disadvantages. The first was that they encouraged volume over quality, and so triggered a torrent of mediocre academic papers. The second was that they led to students choosing well-regarded universities (well regarded, that is, for their research) oblivious of the fact that teaching quality might be very poor - which led in due course to the creation of the TEF.

Complaints

There is not much that an individual student can do if they are concerned about the quality of their education. All universities etc. have complaints processes, but few students will wish to make a fuss which could rebound on them if their professors and tutors feel unfairly criticised. And an isolated complaining student can easily be characterised as a poor learner.

There is an external complaints body - the Office of the Independent Adjudicator - and they seem to do a good job assessing around 1600 appeals each year against specific university decisions. But the OIA can only look at complaints which have been considered first by universities, and it is anyway not empowered or resourced to take a wider interest in the quality of higher education.

Schools Education

The regulation of schools, examination boards etc. raises some interesting issues. The state-provided education market (if you will excuse the word 'market') is highly imperfect. There are no price signals, it is hard for parents to shop around, and it is far from certain that their child will be taken by their first choice of school. Some form of regulation is clearly necessary.

But it is not possible to have highly intrusive systems which monitor the quality of education that is delivered to thousands or millions of pupils. Regulators such as Ofsted (the Office for Standards in Education) and its private sector counterparts therefore mainly report the outcome of inspections of individual schools. Parents can then (in theory if not in practice) choose whether to send their children to particular schools, and the national or local authorities can intervene if an individual school's standards are particularly worrying.

The weakness of this approach is that it relies heavily on parents' ability and willingness to choose a 'better' school for their children. Unfortunately it appears (including from OECD research) that parents are as much influenced by a school's social position than its exam results etc. 'Will my child be mixing with the right sort of other children?' It also appears that many schools tend to respond to competition not by improving teaching and learning but by better promotion and by positioning themselves so that they attract more middle class children. The result is that socially attractive state schools are heavily oversubscribed, and local house prices go through the roof. And of course such schools also attract more than their fair share of better teachers. Luckily, there are plenty of good teachers left to serve in other schools, but this is no thanks to the inspection system.

The Limitations of Inspection

Regulators/Inspectors are obviously reluctant to arrive in a school without warning, but, equally obviously, their presence - especially if teachers have had an opportunity to prepare for it - creates an artificial atmosphere. One pupil's tweet summarised the problem quite nicely:

I hate it when the [the inspectors are] in our school. All my teacher change from A to Z .

There was an interesting development in March 2014. Ofsted had previously generally given schools advance notice of often lengthy visits and evaluations, which allowed schools to put on their best face whilst also maximising the stress experienced by teaching staff. A review of this practice seemed likely to result in the more frequent use of shorter, more efficient monitoring visits.

One issue, which doesn't affect most other regulators, is that Ofsted often use currently-employed school Heads and other senior teachers to inspect other schools - and have on occasion asked such teachers to inspect schools situated close to (and so arguably in competition with) their own. This clearly leads to bias - or at least accusations of bias if the resultant inspection is less than highly complimentary.

Michael Gove, as education secretary in 2012, exempted 'outstanding' schools from being routinely inspected "to free them from bureaucracy". By 2019 this meant that some schools had gone for more than a decade without an Ofsted visit whilst some of those 'outstanding' schools, that had been inspected because of concerns, had been found to have deteriorated - as might have been expected given the absence of inspection. Amanda Spielman, the chief inspector, therefore lobbied the government to allow her to assess all schools, and this request was met in early 2020. (See also the NAO report - below.)

Follow this link for a discussion of regulatory capture and unannounced inspection.

Examinations

There was an interesting government/regulator interaction in the summer of 2012 when the exams regulator, acting as required by their statute, forced the English and Welsh exam bodies to tighten their standards, which had got too lax. The exam boards therefore awarded lower grades to those who had taken exams in the summer of 2012 than had been awarded to those who had taken similar exams a few months earlier, causing numerous complaints from those students who felt they had been disadvantaged - and there were just as strident complaints from schools which felt their reputations would suffer. To his credit, Michael Gove, the Secretary of State for Education, refused to intervene, respecting the independence of the regulator. His Welsh counterpart was weaker, and did require Welsh students' grades to be 'improved'.

It is important to be aware that (a small minority of) teachers under pressure will cheat so as to improve exam results.

It's not quite the same but ... I have to admit that I was amused to hear that at least one (non-UK) private school would allow only their brighter pupils to take their iGCSEs at the school. The rest were made to take the exam at a public exam centre, so sharply improving the school's reported results.

Rethinking Accountability and Inspection

In the longer term, there are important unresolved issues about the purpose of education, and hence what practices should be praised, and what practices criticised, by Ofsted inspectors. The National Curriculum, assessments at age 7 & 11 (SATs) , and Ofsted inspections were introduced because our old friend the Principal-Agent problem had led to many schools failing their pupils in a variety of ways, including failing to ensure that children reached appropriate levels of attainment in key subjects such as English and Maths. This increased focus on readiness for 'the world of work' was never welcomed by all, and that debate continues to this day. But even putting that on one side, there is a good deal of evidence that many parents and teachers have become too obsessed by exam results and the associated league tables. The introduction of Free Schools and Academies - which were given a large measure of management and other freedom whilst remaining state-funded - was to some extent intended to allow parents to choose between different types of education for their offspring.

Ofsted became embroiled in controversy in early 2014 when certain right-leaning commentators accused it of being over-attached to once-trendy ways of teaching, and of being unduly critical of the performance of the modern approaches being trialled by Free Schools and Academies. Coincidentally or not, Ofsted's highly respected Chair was told that she would not be reappointed, although its Chief Executive appeared to retain the confidence of the Secretary of State. (A discussion of the independence of regulators can be found here.)

The Royal Society of Arts published a lengthy but interesting report in 2017 - The Ideal School Exhibition. Its objective was 'to help those who lead and teach in UK schools reclaim ownership of their institutions, their profession and their practice ... To achieve [this] we need to [inter alia]:

- Create a new culture in educational assessment by:

- Making tests harder to teach to by using more closed-question and multiple choice tests;

- Teaching teachers about the dangers of teaching to the test

- Reform the accountability system by:

- Making explicit Ofsted’s emerging role as the guardian of a broad and balanced curriculum; a counterbalance to the pressures of the Department of Education’s (DfE) numbers-based accountability system;

- Making the DfE’s representation of school performance more nuanced and balanced by providing more data about the school, its students and its alumni (so-called ‘destinations data’);

- Withdrawing the ‘right’ for schools to act as their own admissions authority,

- Encourage a teacher-led professional renaissance by:

- Returning the definition of educational excellence to the profession by abolishing the Ofsted ‘Outstanding’ category and getting the inspectorate focused solely on identifying those schools that are either struggling to meet their students’ needs or putting those needs second to their own institutional interests by gaming the system. Schools that are doing neither should be allowed to set their own priorities in line with their own values and vision;

- Supporting and celebrating all grass-roots initiatives designed to improve the quality of teaching and to support the wider contribution schools make to their local communities and society. Initiatives like the National Baccalaureate are of particular importance in the effort to incentivise the provision of a richer, more rounded education.

A 2018 PAC report criticised Ofsted for completing fewer inspections than planned. Almost 300 schools had not been inspected for 10 years. But the main target of the report seemed to be the Department for Education which had cut Ofsted's budget by 52% in real terms between 1999 and 2017, leaving parents and others with no independent assurance about many schools' effectiveness. Ofsted's Chief Inspector (i.e. Chief Exec) Caroline Spielman, made the strong point that it made sense to maintain quality rather than quantity: "It makes wonderful headlines when chief inspectors express opinions that aren't backed up by their evidence, but it doesn't make for such good decisions."

Here is NAO's summary of its report to the PAC in advance of the PAC report mentioned above. Note in particular the second sentence which makes it clear that Ofsted cannot now be regarded as an independent regulator given that DfE tells it how to do its job, and severely constrains its budget.

The Department for Education (the Department) plays an important part in whether the inspection of schools is value for money. The Department affects Ofsted’s funding, how it uses its resources and what it can inspect. The current inspection model, with some schools exempt from re-inspection, others subject to light-touch inspection and the average time between inspections rising, raises questions about whether there is enough independent assurance about schools’ effectiveness to meet the needs of parents, taxpayers and the Department itself. Although government has protected the overall schools budget, it has reduced Ofsted’s budget every year for over a decade while asking it to do more. We think that government needs to be clearer about how it sees Ofsted’s present and future inspection role in the school system as a whole, and resource it accordingly.

Ofsted provides valuable independent assurance about schools’ effectiveness and as such is a vital part of the school system. It has faced significant challenges in recent years, as its budget has reduced and it has struggled to retain staff and deploy enough contracted inspectors. The ultimate measure of the value for money of Ofsted’s inspection of schools is the impact it has on the quality of education, relative to the cost. Ofsted’s spending on school inspection has fallen significantly but it does not have reliable information on efficiency. It also has limited information on impact. Until Ofsted has better information it will be unable to demonstrate that its inspection of schools represents value for money.

Passion?

The Guardian carried this interesting report in 2018:

No chief inspector of schools got off to a stickier start than Amanda Spielman. The education select committee unsuccessfully opposed her appointment in 2016 because, it thought, she lacked not just teaching experience but “passion”.“It is not a job where you simply throw opinions around,” she told the MPs. When one committee member said the chief inspector should be “a crusader for high aspirations and standards”, she replied that “when you start crusading you can often lose track of … objectivity, honesty and integrity”. She does not regret that comment. “The last thing a chief inspector should be is a crusader,” she tells me when we meet at Ofsted’s headquarters in London. “I think the sector is pretty exhausted by an awful lot of crusader language.”

Yet crusading is precisely what critics now accuse her of. When Neena Lall, head of St Stephen’s, an east London primary school, banned girls under eight from wearing a hijab, Spielman leapt to her defence despite parents and community leaders forcing the ban’s reversal. Even more remarkably, she sent inspectors to the school to show solidarity. “School leaders,” she said subsequently, “must have the right to set school uniform policies … to promote cohesion … Ofsted will always back heads who take tough decisions in their pupils’ interests.” Spielman pointedly called on “others in government” to give similar backing. “Muscular liberalism”, she said, was needed “to tackle those who actively undermine fundamental British values”.

This is a nice example of how regulators are often forced to tread quite narrow lines, and will quickly be criticised if they step either side of them. In general, though, I think Ms Spielman was right when she cautioned against any regulator becoming a crusader - as her experience in East London maybe shows.