Eunice Newton Foote was, in 1856, the first person to show that Carbon Dioxide is a greenhouse gas. But, because she was a woman, her paper was presented by a man, and received with indifference.

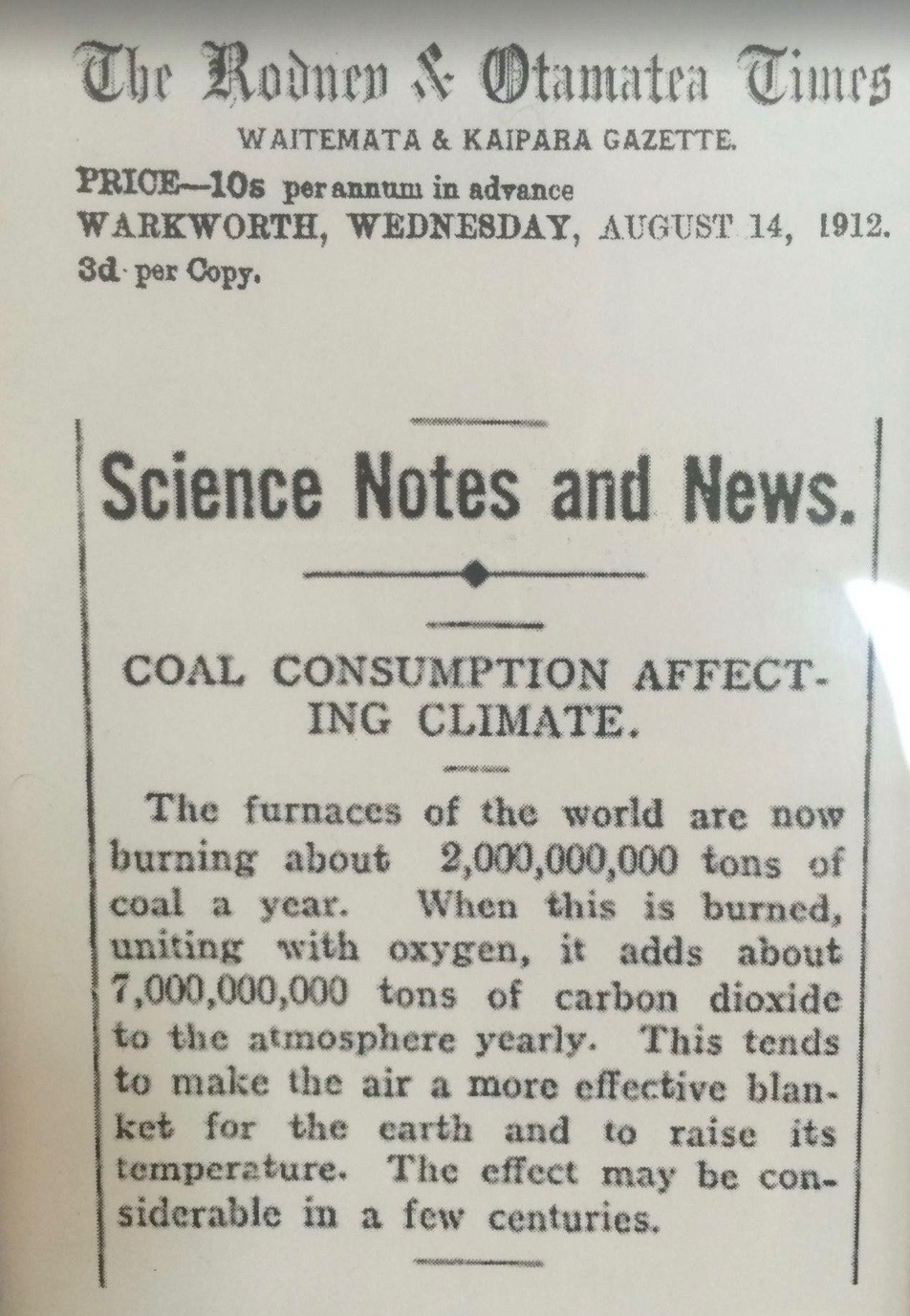

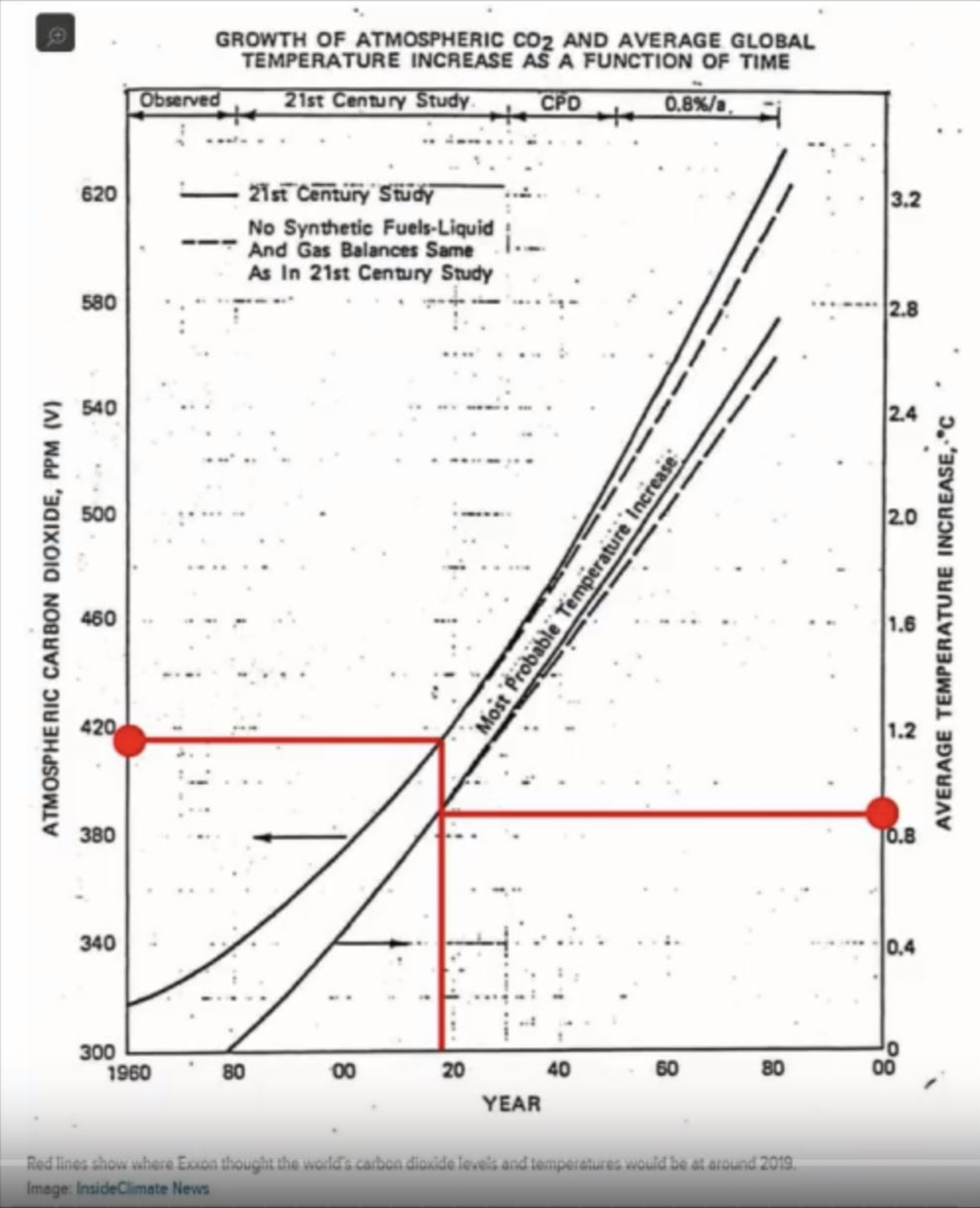

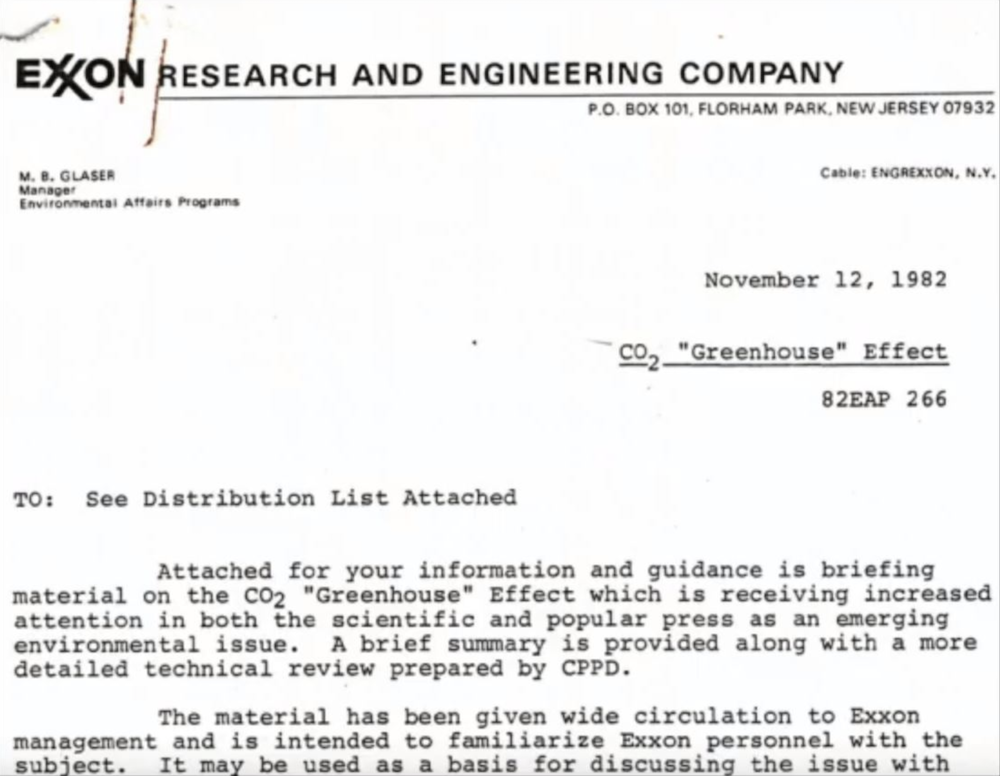

Carbon-created climate change was itself then forecast in 1912 - see newspaper cutting below. The Greenhouse Effect was also recognised as a serious problem by Exxon (owners of Esso in the UK) back in 1982 - see images below. Note in particular that Exxon then recognised it as an emerging environmental issue in both the scientific and popular press.

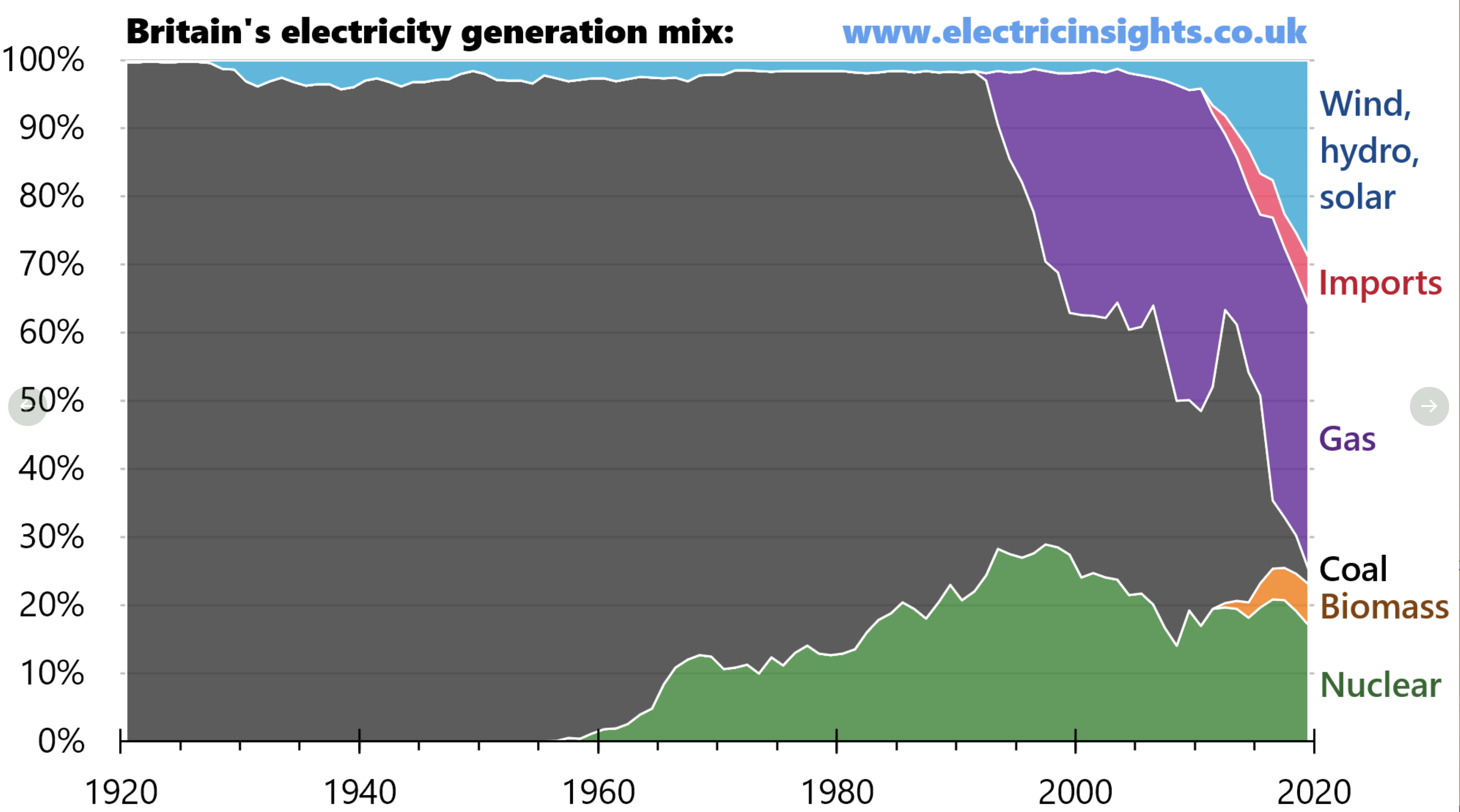

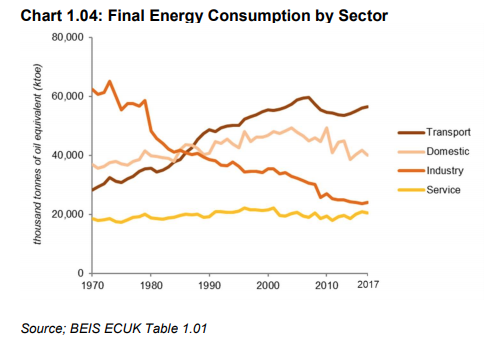

The UK's belated response to the threat of global warming is nicely summarised in these two charts. The rest of this note summarises the background to the trends shown in these charts.

In the light of the developments summarised here, and in particular concerns about greenhouse gases and climate change, the post-2010 Conservative/LibDem Government announced what amounted to a 'dash for gas' whilst simultaneously forcing customers to subsidise maybe £200bn investment in new generation (gas as well as nuclear, wind etc.), probably increasing typical domestic bills by £100pa by 2020, and having an even more severe effect on business' energy bills. The Government's 'gas strategy' included (a) continuing to close coal-fired power stations and (b) continuing to encourage investment in carbon-free nuclear and wind etc. power, as well as (c) also encouraging investment in gas-powered stations so as to provide peak-load back-up to nuclear, wind etc.

One problem with this policy was that it damaged the competitiveness of energy-intensive industries such as steel, chemicals and cement. These industries pointed out that the French and German governments, for instance, are being much slower to load the cost of renewables onto their industries. Sceptics also pointed to the difficulty (verging on impossibility) of doubling nuclear capacity, trebling onshore wind farm capacity, and multiplying offshore wind farm capacity fifteen-fold over the next 15-20 years - unless the European Commission can be persuaded to allow substantial 'state aids'.

The mechanisms under which these outcomes are intended to be achieved (including CFDs - Contracts for Difference) are complex and have been the subject of much criticism from those who think that it is quite wrong to bestow government Ministers with extensive planning powers, who point out that Government intervention in markets creates political and regulatory risk which inevitably feeds through into higher prices, and and who believe that the whole CFD edifice will one day collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. It is well worth reading Professor George Yarrow's 2011 submission in which he argues that 'government policies based on fixing the results of competitive processes are chimeras: it is like fixing the result of a general election and seeking to pretend that this is democracy.'

Interestingly, concern over the effect of these prices increases on industrial competitiveness eventually led the government to decide that energy intensive industries would be partially exempt from these future price rises, thus adding another economic illogicality to the regulatory edifice. Commentators also noted that green taxes which increased the cost of, say, steel produced in the UK would simply lead to increased imports from coal-fuelled economies such as China. Clear evidence of this emerged in late 2015 with the announcement of many thousands of job losses in the UK steel industry.

Biomass power stations were also being encouraged via generous subsidies - although they lead to substantial CO2 emissions - probably more than coal. Their green credentials depend on forests - which provide the biomass - being 'renewable' - which makes long term sense but worsens the greenhouse effect in the shorter term.

Then, in 2017, the government announced that there would be no new subsidies for clean power projects, such as tidal barrages, until 2025 at the earliest. This was to save consumers from any further increases in the annual cost of subsidies for wind, solar and nuclear power. These were already costing £9bn a year.

The government also supports improved energy efficiency, in which the UK lags far behind e.g. Germany. But its strategy seems rather half-hearted, perhaps because of not wanting to appear over-regulatory. And the government may be over-optimistic in its assessment of the likely results of those policies that have been announced. This is because the 'compensation effect' will inevitably lead consumers who have, for instance, improved the insulation of their buildings to respond to their lower energy bills by turning up their thermostats. Similarly, most of us have no doubt become less assiduous about turning off our lights after we have invested in energy efficient bulbs, 'though the phasing out of incandescent light bulbs led to a 29% drop in the demand, from 1007 to 2012, for electricity for lighting.

The government was almost certainly over-optimistic about the energy saving (and lower bills) that would result from the introduction of Smart Meters. The technology appeared pretty dated as soon as it was being rolled out, particularly because the first generation meters could not cope with different suppliers, despite our being encouraged to switch suppliers so as to gain access to lower prices. The National Audit Office, reporting in 2018, said that the program could cost £2 billion more than forecast, and that the promised benefits to customers might never exceed the cost.

There was resistance in late 2020 to the government's proposed flat rate levy to support 'green gas' as this would be highly regressive - i.e. impact proportionately more on low income households.

Nuclear

Despite initial Lib-Dem hesitation, the coalition government eventually developed an increased interest in generating electricity in nuclear power stations. The full story is here, including information about the falling cost of renewable energy.

Climate Change, COVID-19 and GDP

Dieter Helm in mid-2020:

As has been widely noted, the global economic slowdown has been the one thing that has arrested the global rise of emissions. Nothing else has made much difference since 1990, and what has been the great fossil fuel boom. The coronavirus has.

What do we learn from this? That the claim that GDP and emissions are decoupled is simply wrong. They are in fact strongly correlated. But how then do we explain that the UK and the EU have reduced emissions and at the same time increased economic growth? The answer is simple, once climate change is seen as global and it is recognised that the location of emissions does not matter. Overall global economic growth has risen, as has emissions, but Europe has been deindustrialising. Europe’s carbon production tells a flattering story, and its consumption and its carbon emissions tell a very different one. And unfortunately, it is carbon consumption that matters, not territorial emissions. Carbon is not territorial.