Companies such as Google/YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Airbnb and Uber benefit from strong network effects - the phenomenon through which their services become increasingly attractive as more people use them, to the extent that it becomes near impossible for any other company to compete - or for governments to challenge them. (But see the note below suggesting that network effects might matter less than they used to.)

Joanna Bryson, in a fascinating blog about AI, notes that the consequential "winner take all" nature of Internet commerce is also powered by the relatively low cost of transport of the product - i.e. the electronic data. We cannot travel far to buy our groceries, however excellent the shops may be in another country. But we can buy entertainment, social media, search and so on from anywhere in the world. The BBC, for instance, are therefore very concerned about competition from the west coast of America - Netflix, YouTube and the rest

But there are clear signs that these hugely powerful companies are to a great extent immune from pressure to be good corporate citizens, and may also be coming under less and less pressure to remain efficient, or to innovate,.

This web page summarises the main criticisms of the behaviour and culture of the Technology Giants. Particular examples of their alleged failings may be found towards the end of this web page. A second page considers how regulation might best tackle the problems.

There are of course other concerns. What will happen, for instance, when one of them fails - as they are bound to do? All our cloud data - our emails, our photos, our documents - will presumably be sold to the highest bidder. I am not aware that legislators or regulators have yet to say much about this risk.

The Criticisms

The following paragraphs summarise the principal criticisms.

They are said to export the American 'see you in court' approach to regulation. Regulation, they believe, is for 'the guidance of wise men and the observance of fools'. The Times called them the 'Predators of the internet who do as they please'. They like to 'move fast and break things'.

- Uber, for instance, is said by the New York Times to have 'tended to barrel into new markets by flouting local laws, part of a combative approach to expand globally'. And according to the same newspaper, Uber developed an app which ensured that city officials were not able to book a car and so scrutinise the service.

- Facebook certainly seemed unperturbed when it was fined €110m (£94m) by the EU for providing misleading information about its 2014 takeover of WhatsApp.

- Airbnb will not provide city authorities with data about their lettings, even though (or because?) there are increasing concerns that the site is hosting systemetised listings which are in effect 'ghost hotels' or 'distributed hotels'.

There are growing concerns that the Internet Giants - and Google in particular - are exploiting and abusing their dominant position by squashing potential competitors before they get a chance to establish themselves. Facebook was allowed to buy messaging app WhatsApp for $19bn in 2014 and photo-sharing app Instagram for $1bn in 2012, while Google bought online advertising agency DoubleClick in 2007. As the merging companies were arguably not competing strongly with each other at that time (although they might in future) normal merger control legislation was not triggered.

A commentator called Kassandra commented that few if any had appreciated that data can be weaponized. 'The internet is a fantastic resource. Social media is not. It was dreamed up by naive American college kids who had no sense that personal information cannot only be used for advertising. It can also be weaponized. Had they bothered to read or shown any interest in totalitarianism, they would have known. But they came of age in the early 2000's when the march of liberal democracy and globalization seemed unstoppable. Or maybe they just didn't care about politics. Maybe they were simply oblivious about the world around them.'

One wonders whether any regulations can adequately protect the interests of consumers faced with increasing monetisation of personal data. The following extracts from a letter to the FT summarised concerns very well:

... The consumer will never own the data or the algorithms. ... Every moment, your data relating to browsing, calling, online, social media, location tracking and so on is being churned through a multiverse of data warehouses. If you have been browsing about a certain medicine, correlating to a call to an oncologist and a search for a nearby pharmacy, this can consequently be packaged as a data intelligence report and sold to your medical insurance company. This is just one of the myriad ways monetisation is being unleashed on unsuspecting consumers across the world.

The data protection regulations, although a step in the right direction, are usually still heavily tilted in favour of the corporate giants and still focused on cross-border transfers than on the real risks of monetisation. The fines imposed on the Silicon Valley giants are minuscule compared with the money they have made from data monetisation efforts. And this is all achieved in the age that is still a forerunner to the era of artificial intelligence and quantum computing.

The very concept of data privacy is archaic and academic. The tech giants are moving faster than this philosophical debate about data privacy. All the sound-bites from the tech giants are mere smoke and mirrors. Unless we revisit our concepts of what is data privacy for this new age of data monetisation, we will never really grapple with the real challenges and how to enforce meaningful regulation that really sets out to protect the consumer.

Syed Wajahat Ali

Zeynep Tufekci drew attention to one interesting example in 2018. One medical company was buying individuals' temperature data that had been uploaded to another company which had supplied Internet-connected thermometers. It all sounded very benign but Ms Tufekci was concerned that the customers hadn't thought through the implications of having health data sold to anyone at all, including advertisers, and/or integrated into countless databases.

Evan Williams — a Twitter founder and co-creator of Blogger — was reported as follows in 2017:-

“I think the internet is broken ... And it’s a lot more obvious to a lot of people that it’s broken.” People are using Facebook to showcase suicides, beatings and murder, in real time. Twitter is a hive of trolling and abuse that it seems unable to stop. Fake news, whether created for ideology or profit, runs rampant. Four out of 10 adult internet users said in a Pew survey that they had been harassed online. “I thought once everybody could speak freely and exchange information and ideas, the world is automatically going to be a better place,” Mr. Williams says. “I was wrong about that.”

Twitter's other co-founder and current chief executive, Jack Dorsey, admitted in 2019 that his app's 'vibe' depressed him and that Twitter had so far failed to find an effective way to curb online abuse, leaving too great a burden on the victims of abuse. "Most of our system today works reactively to someone reporting it. If they don't report, we don't see it. Doesn't scale. Hence the need [in future] to focus on proactive."

John Lanchester argued (Sunday Times October 2017 )that Alphabet/Google/YouTube and Facebook/Instagram were both walking the fine line between ethical growth and making even more money by 'doing evil'. Quoting an industry insider:-

“YouTube knows they have lots of dirty things going on and are keen to try and do some good to alleviate it, ... “Terrorist and extremist content, stolen content, copyright violations. That kind of thing. But Google, in my experience, knows that there are ambiguities, moral doubts, around some of what they do, and at least they try to think about it. Facebook just doesn’t care. When you’re in a room with them you can tell. They’re” — he took a moment to find the right word — “scuzzy.”

It was telling, of course, that Facebook's founder, Mark Zuckerberg, cared little for personal privacy right from the start. A Harvard friend asked him how he had managed to obtain so much personal data from fellow students. "They 'trust me'. Dumb f***s" he replied, offering to share the information with that friend.

Facebook, Twitter and others distribute fake news and other attention-grabbing content, regardless of its quality, veracity or decency, including material which encourages terrorism. It is well established that detailed guides showing how to make nail bombs, and ricin poison are freely available on Facebook and YouTube.

Equally seriously, there have been increasing numbers of allegations that both governments and powerful individuals have begun to mis-use social media so as to influence the outcome of elections and referendums, most noticeably the 2016 election of US President Donald Trump and the 2016 Brexit Referendum in the UK. These issues are too complex and detailed to be adequately summarised here, but they are thoroughly and forensically examined in the 2018 interim report Disinformation and ‘fake news' by the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. But the Government accepted only three of the committee's 42 recommendations.

Some commentators have drawn attention to the tendency of some technology to encourage 'extremism', with YouTube's algorithms in particular being accused of driving people from reasonable videos to ever more extreme content on those subjects because it captures their attention. “Truth” doesn’t enter into it. Google’s mission statement is to “organise the world’s information and make it accessible”. It doesn’t include anything about separating accuracy from untruth.

It must certainly be increasingly irritating (to use a mild word) for the established media to watch Facebook and others publish material which would lead to others being brought low. Imagine what would happen if the BBC decided that they would allow the public to broadcast murders and suicides live on one of their channels.

There is a related (and very real) concern that so much advertising has switched to Big Tech that it is now very hard to fund mainstream and investigative journalism, and this in turn is leaving space for fake news and extremism to thrive on the web.

Nick Srnicek has described data as the modern equivalent of oil - essential to the modern economy and maybe needing something like the 1911 anti-trust break-up of Rockefeller's Standard Oil. And Facebook's rather cavalier sharing of data with Cambridge Analytica blew up in its face in March 2018 - see further below. Facebook etc.'s ability to extract the value of data from consumers is perhaps a modern form of previous generations' monopolists' ability to extract other forms of monopoly rents, such as higher prices.

Joanna Bryson has raised an interesting tax point in her AI blog. "Every interaction with Google or Facebook is a barter of information. With no money changing hands, there is no tax revenue ... [We may need] to turn instead to taxing wealth ... which is becoming harder [to hide] because of the information age."

She also believes that we are in danger, as in the 19th/early 20th Centuries, of allowing technology to increase inequality and hence political polarisation.

There is also the danger that algorithmic news poses a risk to democracy as 1.2 billion daily Facebook users, for instance, mainly listen to louder echoes of their own voices - the so-called filter bubble. But Facebook’s relatively modest efforts to curb misinformation have been met with fury on the right, with Breitbart and The Daily Caller fuming that Facebook had teamed up with liberal hacks motivated by partisanship. If Facebook were to take more significant action, like hiring human editors, creating a reputational system or paying journalists, the company would instantly become something it has long resisted: a media company rather than a neutral tech platform. Facebook’s personalisation of its news feeds would perhaps be less of an issue if it were not crowding out every other source – but as a result it is beginning to appear that Facebook must be responsible for finding solutions to its problems.

There is also the danger that algorithmic news poses a risk to democracy as 1.2 billion daily Facebook users, for instance, mainly listen to louder echoes of their own voices - the so-called filter bubble. But Facebook’s relatively modest efforts to curb misinformation have been met with fury on the right, with Breitbart and The Daily Caller fuming that Facebook had teamed up with liberal hacks motivated by partisanship. If Facebook were to take more significant action, like hiring human editors, creating a reputational system or paying journalists, the company would instantly become something it has long resisted: a media company rather than a neutral tech platform. Facebook’s personalisation of its news feeds would perhaps be less of an issue if it were not crowding out every other source – but as a result it is beginning to appear that Facebook must be responsible for finding solutions to its problems.

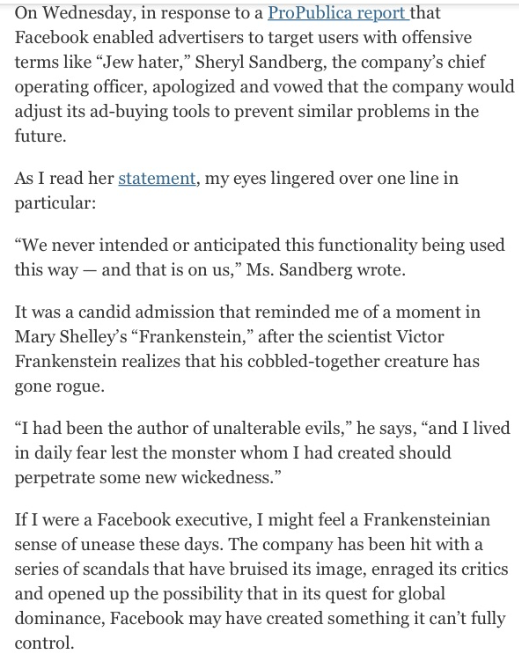

I was going to give the last word, in this section, to Facebook's apology - see box on the right. But then I read Zeynep Tufekci's excoriating piece in Wired in which she drew attention to the huge number of times that Mark Zuckerberg and his colleagues have previously apologised for their actions - but only after being challenged - including the company's 2011 admission to the Federal Trade Commission that it had deceptively promised privacy to its users and then repeatedly broken that promise. It very much looks as though Facebook's unacceptable behaviour is hard-wired into its culture, and nothing will change until politicians decide that its apologies are insufficient and that a firm response is needed.

Part of the explanation for Facebook's behaviour may have been included in a Buzzfeed News report in late 2018 which cited Facebook employees' complaints of a 'sycophantic' culture in which they faced pressure 'to drink the Kool-Aid" and 'only talk about positive things'. Organisations which so obviously fail to let their staff 'speak truth to power' are almost certainly setting themselves up to have big problems.

Nick Clegg (Facebook's 'Head of Global Affairs, and former Deputy Prime Minister) mounted a European media blitz in June 2019 but failed to convince many critics. The Times' Hugo Rifkind commented -

[Clegg argued that] "there is absolutely no evidence that [Russian interference] happened in the Brexit referendum.” ... Clegg was referring to adverts. .. .He must know, though, that this is a dishonest foundation from which to build a broader defence. Exactly why was perfectly illustrated within moments, when stories about his remarks turned up on the Facebook pages of the Russian news services RT.com and Sputnik. This, before we even get into fake accounts, trolls and user groups of the sort that, once upon a time, Clegg himself used to sound quite concerned about. Last year, when it briefly looked as though his post-political career might be as a mere newspaper columnist, he wrote in the i newspaper that “we’re all familiar with the evidence of Russia-based bots and trolls spreading pro-Brexit messages online”. What was it about going to work for the fifth richest man in the world that changed his mind, I wonder?

But if you think Russia is the point, then you still don’t understand the point. Inasmuch as Russia has managed to skew western politics via social media, it has done so only by plugging itself into the chaotic orgy of hate and misinformation that the rest of the world is already enthusiastically conducting. The growth of social media has not only run concurrent with Brexit and Trump. It has also happened alongside the rise of anti-vax movements, and of new currents of hatred towards both Jews and Muslims on the extreme left and right. There has been genocide in Myanmar, and anti-Muslim mobs in Sri Lanka. We have seen Rodrigo Duterte’s populist surge in the Philippines, and Jair Bolsonaro’s in Brazil, and Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and Le Pen and the gilets jaunes in France, and Matteo Salvini in Italy, and on, and on.

At The Times CEO summit a fortnight ago, I interviewed Clegg and I asked him if he felt Facebook was responsible for any of this. He said not. “Populism wasn’t invented fifteen years ago,” Clegg told me. “You must accept it’s having something of a ... heyday?” I said, a little weakly. Nothing to do with Facebook, said Clegg. He cited the populism of the 1920s and ’30s. Same thing, he said. Same roots, same drivers. In other words, it wasn’t only Russia that was innocent of fomenting division on social media, but everybody. It would all be happening anyway. Afterwards, a colleague asked me whether I’d been making those incredulous facial expressions on purpose. (No.) ...

As it happens, I think Facebook is on broadly the right track with its political responsibilities. When compared to the opportune nihilism of Twitter, certainly, its newfound global civic aspirations are to be welcomed. What grates, still, is the absolute refusal of the company to accept its own hideous culpability for this global age of political madness. Far more than Russia, or even shadowy billionaires, the culprits are virality, peer pressure, and wilfully engineered addictions to both approval and rage. Many of us have come to live by them, so it is no surprise that politicians now campaign by them, too. I would be more inclined to believe that Facebook could solve that problem if just once, and with absolute clarity, it would admit it was actually there.

Facebook faced a significant 'Stop Hate for Profit' advertising boycott in the summer of 2020 but its pre-announced Oversight Board had still not been launched, and its share price continued to rise.

Once Facebook's Oversight Board was up and running, commentators pointed out that many of its decisions could not easily be separated from Facebook's design decisions that Facebook had declared 'off-limits'. "Content-moderation decisions are momentous, but they are as momentous as they are because of Facebook’s engineering decisions and other choices that determine which speech proliferates on the platform, how quickly it spreads, which users see it, and in what context they see it. The board has effectively been directed to take the architecture of Facebook’s platform as a given."

Can data be owned?

It is interesting, by the way, to consider whether data can be (or is) owned like other property, It is hard to see that anyone can own the fact that something happened (Ms X bought item Y). And an electronic or other record of that fact can easily be copied - many times. And yet data is sold, which suggests that it has indeed become property. But who does it belong to? Does anyone have the right to control its destination?

Cookies

Some of us, but far from all, know that our browsing history, saved in the form of cookies, can significantly affect the way in which companies deal with us. The most obvious example are the cookies saved by travel companies, which reveal whether we have previously enquired about a particular flight or holiday. If we have, then the company is less likely to offer us their best deal, believing that our repeated searches suggest that we are very likely to become a customer. (See for instance Travel site cookies milk you for dough in the Sunday Times - 24 June 2018.

Does it matter? I would argue that this is no more than an automated example of the behaviour of any salesperson who has the ability to price a product (such as a car) according to their estimate of the customer's keenness to buy. But it's a bit less obvious - sneaky even.

Genes

A March 2019 article in the New Scientist reminded us that we give away some pretty fundamental information when sharing our DNA with companies such as AncestryDNA and 23andMe.

Examples

The FT carried this interesting report in in April 2017:

Facebook blamed human error for its failure to remove dozens of images and videos depicting child pornography after they were flagged to the company. The Times newspaper reported that it had alerted the social media giant, using a dummy Facebook profile, to potentially illegal content that was posted on to its website by users, including images of an allegedly violent sexual assault on a child and cartoons of child abuse. The British newspaper accused Facebook of failing to remove many of the images but the company said this was because of human oversight and that its reviewers should have spotted that the content should be removed. ...“We are always looking for other ways to use automation to make our work easy, but ultimately content review is manual,” said Monika Bickert, head of global policy management at Facebook in a past interview with the Financial Times.

This is a clear admission of failure of quality control. I have no doubt that most media organisations would have run into severe trouble - and probably been prosecuted - if they had behaved like Facebook. But I am not aware that any formal action has yet been taken against the company.

Later that month, a man killed his daughter and then himself whilst live-streaming his actions on Facebook Live. The company had previously streamed a video which showed that a man chose 74 year old Robert Godwin Snr at random and then shot him. Again, the company's attitude seemed to be that its customers' wish to view live video outweighed any moral or other pressure that the content should be pre-approved. Presumably nothing will change unless and until someone prominent is killed by someone seeking Facebook fame - though its COO was reported to have had a moment of doubt - see box on right.

It didn't help Facebook's reputation that Channel 4's Dispatches was able to show that the company trainers told trainee moderators not to take down footage of, for instance, the 'repeated kicking, beating or slapping of a child or animal' as it was 'for better user experience ... it's all about making money at the end of the day'.

The Times reported in November 2017 that a YouTube channel Toy Freaks - where a parent posted hundreds of videos of two girls in distress - was not removed until it had been reported to the channel multiple times over more than a year.

And there were numerous complaints of inappropriate material appearing on YouTube Kids.

Uber admitted in November 2017 that it had concealed a data breach in October 2016 in which hackers accessed the personal details of 57 million customers worldwide. Instead of reporting the breach to the authorities, the company paid the hackers $100,000 to keep silent and deleted the data, although of course no-one, least of all Uber, can be sure that they did so.

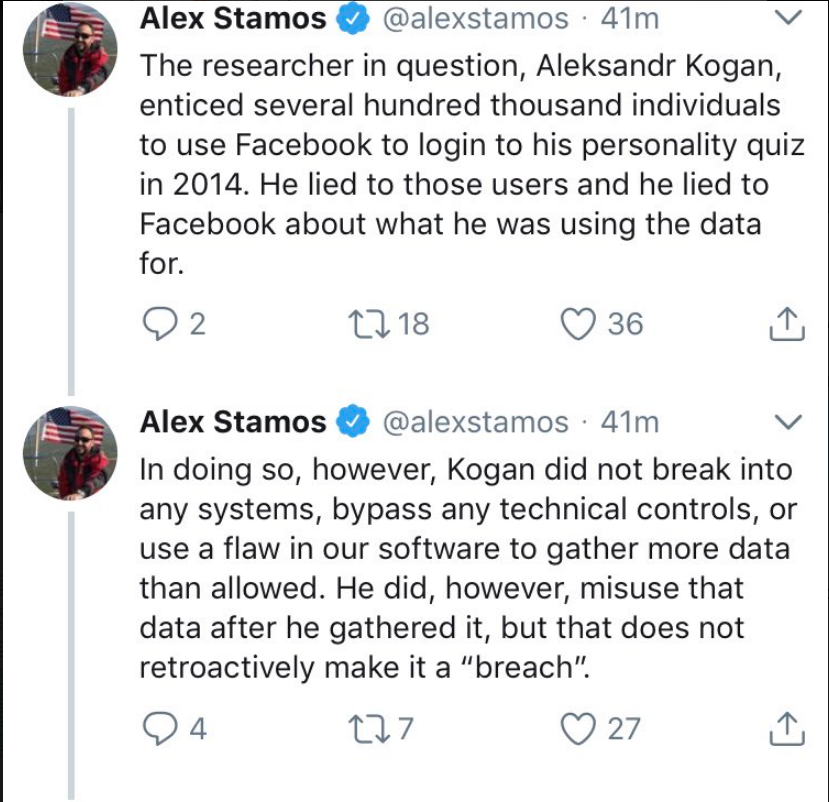

Facebook was in the firing line again in March 2018 when UK, EU and US regulators and politicians began to investigate reports that Cambridge Analytica, a data analysis firm employed by Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, mined the personal data of 50m Facebook users to create profiles to target them in elections. It was alleged that the company broke Facebook’s rules by using data collected solely for research, but it seems astonishing that Facebook handed over the data so willingly and without subsequently auditing its use. Facebook's Head of Security's comment is on the right. The Guardian's Alex Hern's response was devastating:

Facebook was in the firing line again in March 2018 when UK, EU and US regulators and politicians began to investigate reports that Cambridge Analytica, a data analysis firm employed by Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, mined the personal data of 50m Facebook users to create profiles to target them in elections. It was alleged that the company broke Facebook’s rules by using data collected solely for research, but it seems astonishing that Facebook handed over the data so willingly and without subsequently auditing its use. Facebook's Head of Security's comment is on the right. The Guardian's Alex Hern's response was devastating:

If I walk into a hospital and tell them I’m the butt inspector and they should give me pictures of all their patients’ butts and they do, that’s a data breach, regardless of whether the hospital obtained the butt pics with patient consent.

The difficulty for Facebook was that its business depends on sharing information about its users with others, including advertisers and the many companies whose apps are accessed via, and interact with, Facebook. As Hugo Rifkind pointed out: "the idea of a) harvesting data and then, b) selling a service based on having it is not some nefarious perversion of utopian innocence ... Rather, it is, and always has been, what Facebook is all about. It is what the whole damn website is for."

Facebook's lawyers will have been acutely aware of the danger of crossing some invisible line and so breaching data protection legislation. But if they are shown to have drawn the line in the wrong place, or failed to guard the boundary effectively enough, then Facebook could be in serious trouble.

Facebook's lawyers will have been acutely aware of the danger of crossing some invisible line and so breaching data protection legislation. But if they are shown to have drawn the line in the wrong place, or failed to guard the boundary effectively enough, then Facebook could be in serious trouble.

Stig Abell (former Director of the Press Complaints Commission and also former Managing Editor of the Sun newspaper) complained to Twitter in 2018 that a man had started posting about how he knew where Mr Abell lived and - in detail - how he wanted to rape Mr Abell's wife. Twitter said that it was not a breach of its rules, though - under pressure - it later changed its mind.

Hugo Rifkind pointed out that Twitter had told a Parliamentary committee that it investigates c.6.4 million dodgy or abusive accounts each week - with a staff of only 3,800!

And an Instagram employee was reported, in 2018, to have remarked that new features, such as those that might reduce harassment, would not be allowed to 'hurt other metrics. A feature might decrease harassment by 10%, but if it decreases users by 1% that's not a trade off that will fly."

The Times reported in January 2019 that Facebook was paying $20 pcm to children as young as 13 for access to their phone and web activity, including private messages, internet searches, emails and shopping.

14 year old Molly Russell took her own life in early 2014. It appeared that she had probably been suffering from depression and an eating disorder and her researches on Facebook-owned Instagram and elsewhere had triggered algorithms which had drawn her attention to extremely disturbing and/or graphic material featuring self-harm and suicide. A Sunday Times investigation found numerous graphic images of self harm on social media used by Molly, including blood spattered arms showing self-inflicted wounds, and a picture of a teenage girl hanging. Pinterest sent Molly a personalised email a month after her death saying "I can't tell you how many times I wish I was dead, and attaching self-harm images including a slashed thigh. Molly's father said that he had "no doubt that Instagram helped kill [his] daughter" and the story attracted a lot of media attention only a few weeks before the government was due to publish a White Paper on internet harm.

By way of background, however, it is important to remember that there are very few teenage suicides each year (31 aged under 15 in the UK in 2017) and that many factors inevitably combine before troubled youngsters take their own lives. And Instagram said that it had been advised that sharing mental health struggles could often help recovery.

The 2019 killings at two New Zealand mosques were live streamed on Facebook, and the video copied to many other social media sites.

Notes

MIT's Catherine Tucker has pointed out the network effects might matter less than they used to. Two of her very readable articles are here and here.

As of around 2017:

- The 'Big Four' technology giants - Amazon, Facebook, Alphabet (i.e. Google & YouTube) and Netflix - were valued on Wall Street at around $1.5 trillion in May 2017.

- Facebook has over 2 billion users, approaching one-third of the World's population.

- Google has 87% of the search market in the USA, and 83% in the UK.

- Amazon has 43% of the online retail market in the USA and 16% in the UK.

William Perrin kindly drew my attention to Christopher Sirrs' interesting 2015 commentary on the 1972 Robens Report on health and safety which described a fractured and ineffective regulatory landscape very much like that today on social media.