Policy makers and regulators will often have frequent interactions with Board members and senior executives of the large organisations within their sphere of interest. But it is in practice very difficult to tell whether such senior people are providing anything like a true description of their thinking. If they have something to hide, they may well lie - and lie very convincingly.

Equally, their middle managers - compliance staff, finance teams etc. - will sometimes not have the foggiest idea what their senior executives are really thinking. Principal-agent theory tells us that their bosses will themselves often not have a clue what is happening in the far reaches and lower rungs of their organisation - and they are likely also suffer from herd behaviour, group-think and similar problems.

Please read Understanding Organisations if you would like to know more about the behaviours mentioned above

The culture of the whole entity can sometimes be totally rotten. The authors of Freakonomics pointed out that 'Cheating ... is a prominent feature in just about every human endeavour. Cheating is a primordial economic act: getting more for less'. It is often held in check in various ways and for various reasons. But it can become second nature when the reputation, or profitability, or even the existence of an entity is under threat.

Organisations such as hospitals can go to desperate lengths to cover up their mistakes.

- The examples of Mid-Staffs, Morecambe Bay and Shrewsbury are discussed here.

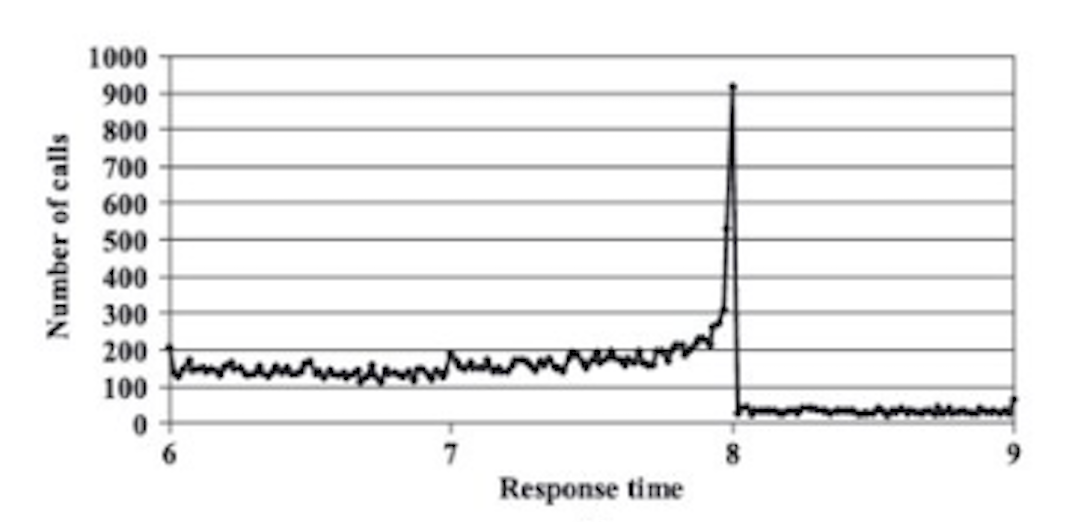

- Less seriously, the Commission for Health Improvement showed, in 2003, that a third of Ambulance Trusts made manual corrections so as to show that a higher proportion of their response times were recorded as taking less than the national 8 minute target. Here is a chart showing adjusted response times (by number of calls) for one trust:

And win-at-all-costs companies can take appalling risks with health and safety:

- Boeing was a classic example in the years when it developed the 737-Max.

- “Your integrity is priority 4” — message from a Boeing manager to an employee in March 2018, after the worker said they were “not lying to the FAA” and would “leave that to people who have no integrity”.

- As was Kingspan - the industry leader that advertised and sold supposedly non-combustible insulation of the sort that burned all too readily outside Grenfell Tower.

- One employee shamefacedly told the Grenfell Inquiry that "You get to the point when you are embroiled in the culture of a business and it just becomes second nature.”

Senior Executives' Characters

Senior executives, senior partners, senior aircraft and ship captains, hospital consultants etc. are so powerful that they easily become isolated from ordinary people, and even more so from their front line staff and their concerns.

Some of them overcome the problem better than others. Crew Resource Management, mandatory protocols and generational change are making a big difference in hospitals and transport. But many other top executives have too much confidence in their own judgement and opinions, whilst the scale of their operations or responsibilities mean that they have to think in abstract terms where risks, and even death rates, become mere numbers that have to be managed. This can easily cause whole management teams to characterise as naive or unworldly anyone - and in particular a whistle blower or journalist - who expresses any concern about organisational culture. Lord Browne, BP's Chief Exec at the time of the Texas City disaster, was said by his executive assistant to show 'no passion, no curiosity [and] no interest' in safety.

It can be worse if an organisation is highly focused on the power and influence of a single individual, often someone with a heroic leadership style. Their direct reports then spend all their time trying to second guess their hero's wishes, rather than think for themselves or commission analysis which might challenge their leader's views. This was certainly a problem at Toshiba where investigators into a huge accounting scandal found "a corporate culture where it was impossible to go against one's bosses' wishes".

Researchers seem to find it difficult to explain why companies that (apparently honestly) believe themselves to be ethically virtuous often find themselves doing unvirtuous things. It may be that some senior executives' illusion of moral superiority allows them to behave badly because they think they really are, deep down, good people.

The wider the power gap, the more difficult it can be to communicate even urgent concerns. Junior doctor Rachel Clarke* describes her distress when she failed to challenge the appalling behaviour of one senior consultant doctor.

Mr Skipton ... stared up in trepidation as my boss, impatient to get to theatre as quickly as possible, alighted at the bedside. ... Without so much as an introduction, he broke the news to the patient of his terminal illness by turning away to the bedside entourage and muttering, perfectly audibly, "Get a palliative care nurse to come and see him". No one had even told 'him' he had cancer.

As panic began to rise in Mr Skipton's face, I remember catching the ward sister's eye to see her cringing alongside me. But trying to undo the damage would take so long and the ward round was already sweeping on. I had a moment to act decisively. I could have chosen to earn my consultant's wrath by remaining at my patient's bedside. Instead, to my shame, I scuttled dutifully after my boss, leaving someone else to pick up the pieces.

Her subsequent thoughts on this incident, bearing in mind what had happened at Stafford, are here.

(*The above extracts are from Rachel's book Your Life in My Hands.)

Even if middle managers (the agents) are trying hard to achieve the aims set for them by their seniors (their principals), it is absolutely certain that their communications to their seniors will be less than totally honest or frank. Tim Harford puts in nicely in his book Adapt:

'There is a limit to how much honest feedback most leaders really want to hear; and, because we know this, most of us sugar-coat our opinions whenever we speak to a powerful person. In a deep hierarchy, that process is repeated many times, until the truth is utterly concealed inside a thick layer of sweet-talk. There is some evidence that the more ambitious a person is, the more he will choose to be a yes-man - and with good reason because yes-men tend to be rewarded.

Even when leaders and managers genuinely want honest feedback, they may not receive it. At every stage in a plan, junior managers or petty bureaucrats must tell their superiors what resources they need and what they propose to do with them. There are a number of plausible lies they might choose to tell, including over-promising in the hope of winning influence as go-getters, or stressing the impossibility of a task and the vast resources needed to deliver success, in the hope of providing a pleasant surprise. Actually telling the unvarnished truth is unlikely to be the best strategy in a bureaucratic hierarchy. Even if someone does tell the truth, how is the senior decision-maker the honest opinion from some cynical protestation?

A much more detailed analysis of the difficulty of 'speaking truth to power' may be found here.

At another level, the behaviour of large companies' senior executives has become quite fascinating. One begins to wonder whether big business has succeeded warfare as the most exciting form of competition between human organisations. Some modern boardrooms appear to attract those who would, in previous generations, have sought to command large armies. Instead of invasions, we nowadays have corporate takeovers; instead of gold braid and military honours, we have executive salaries. The leading actors therefore remain the odd combination of hugely ambitious, sometimes inspirational, but too often also highly self-absorbed and disastrously inept. For Haig, Montgomery, Patton and MacArthur substitute Dick Fuld, Fred Goodwin, John Gutfreund, Tony Hayward, Jeffrey Skilling, Bob Diamond, Rajat Gupta? Indeed, I understand that Turkish Islamists rather bitterly note that the mujahids or aspiring warriors of old have become the muteahhits or construction tycoons of today.

It certainly seems to be the case that power changes the behaviour of previously decent men and women. 'Power corrupts ... etc.'. It is perhaps inevitable that powerful CEOs' sense of right and wrong becomes aligned with the norms and expectations of others who are similarly rich and powerful. Neuroscientist and psychologist Ian Robertson goes further and draws attention to research which shows that power increases testosterone levels which in turn increases the uptake of dopamine in the brain, leading to increased egocentricity and reduced empathy (New Scientist 7 July 2012). Power also reduces anxiety and increases appetite for risk.

And yet, as the FT's Lucy Kellaway points out: "Modern CEOs seem to have no [public] opinions, especially not negative ones. If they feel one coming on, they have been trained by their lawyers and PR advisers to suppress it." It is certainly difficult these days for CEOs to correct the mistakes or improve the behaviour of their organisation without laying themselves open to the charge that previous behaviour was in some sense faulty and so worthy of criticism and/or claims for compensation.

Senior managers are certainly, all too often, very concerned to appear infallible (and un-sue-able). Organisations therefore get locked into defensive modes, from which they find it increasingly difficult to extricate themselves - and so the problems get worse. The reputation of BP's Tony Hayward was for instance badly damaged (yet further) when he failed to answer many of the questions put to him by US Congressmen in June 2010. Barclays' Bob Diamond also did himself no favours when responding so blandly to UK politicians' questions in July 2012.

Sadly, therefore, regulators have become increasingly circumspect (mealy mouthed?) in the way in which they communicate with CEOs, their lawyers and their PR advisers. The financial services 'Big Bang' saw an end to the ability of "the [Bank of England] Governor's eyebrows' to terrify City of London financial services. And I don't think any regulator would nowadays get away with the following behaviour even if, like Sir Thomas Barlow, they were a business man brought into government during World War 2:-

'I chanced to be in Tommy Barlow's room when he had a question for a manufacturer who was suspected of rigging [wartime] restrictions to his firm's advantage. Tommy began his address ... "I wonder if you have any idea, Mr X, how I long to be relieved of this job [or ] if you have any idea of the reason ... It is, Mr X, because I shall never have to meet a man like you again'. [Francis Meynell, My Lives]

Diffuse Responsibility

Knowledge of, and/or responsibility for, problems is often widely shared within large organisations, but it is then often the case that no-one feels responsible for addressing or even highlighting the problem. One example was the poor maintenance and terrible safety record at BP's Texas City Refinery, where an explosion in 2005 killed 15 and injured over 170 more. The problems were readily apparent to most employees and managers but - partly under pressure to save money - no-one felt responsible for doing anything about them.

Much the same was true of Bernie Madoff's Ponzi scheme where quite a few financial professionals had worked out that something fishy was going on, but saw no need to do anything more than avoid dealing with him.

And just about everyone in Westminster knew that Members of Parliament were receiving over-generous expenses payments as recompense for their low salaries, but hardly anyone saw much wrong with this ... until Heather Brooke and the Daily Telegraph published the expenses claims in 2009 - triggering immediate uproar outside Westminster, and a few prosecutions. Indeed, many MPs had previously supported an attempt to exclude their expenses claims from the Freedom of Information Act.

The diffusion of responsibility is exacerbated if there are frequent changes of management. This was part of the problem at Texas City as the over-worked men 'close to the valve' stayed put, whilst their managers generally moved on very rapidly, away from an old refinery which lacked the prestige of many of BP's other locations. Managers were not therefore in post long enough to both understand the issues and then have the time and inclination to do much about them.

And then there are the Lawyers ...

Be aware, too, that some lawyers, for various reasons, end up unnecessarily terrifying their Board-level clients when advising them how to respond to regulatory inquiries. Most directors and senior managers should have little to fear if they make it clear that, if there is a problem somewhere in their organisation, they will address it. No regulator expects directors to know everything that is happening (note the Principal-Agent problem) but they do expect them to deal openly and honestly with the regulator, and to correct problems when they are identified.