This is a relatively new webpage to which I am adding international data as I come across it. Contributions, comments and corrections would be very welcome.

Overview

Different cultures clearly differ in their approach to regulation. Western cultures, for instance, pay greater respect to individual rights than to obligations to wider society. Surveillance, on the other hand, is more accepted in some other cultures, and many communities tolerate village and family punishment of those that step out of line.

UK businesses are less regulated that many of our competitors. Indeed, the UK, when within the EU, strongly resisted constant pressure to implement yet further social legislation, whilst US businesses are in effect intensively regulated via the threat of private litigation driven by a strong compensation culture.

- The UK Trade and Industry Committee accordingly reported, on 21 March 2005, that it could "find little hard evidence to support the assertion that UK competitiveness is being threatened by overly stringent employment legislation".

- The OECD reckons that the UK is the second-least regulated OECD country when it comes to product market regulation, and the fourth-least for employment legislation.

- The World Economic Forum and the World Bank come to similar conclusions when assessing global competitiveness and ease of doing business respectively.

Respect for property maybe peaks in Anglo-Saxon cultures - "An Englishman's castle" and all that. Crimes against property, including theft, seem to be punished relatively more seriously than violence. Which leads naturally to a look at regulation in ...

The USA

Justin Webb, writing in The Times in August 2017, commented that "The libertarians squeal but here is the dirty truth: Americans like regulation". Others tell me - and my own experience suggests - that rules tend to be enforced more strictly in the States than in the UK, with less room for common sense. All types of law enforcement officers can often appear tyrannical to British eyes, and prosecutors, who have to run for office, can be over-zealous.

Justin Webb quoted some fun examples - interior designers need to be registered and take exams before they can offer their services in Houston, Texas. And a manicurist was fined $1,000 for washing hair in Tennessee without being licensed as a 'shampoo technician'. British travelers to the States also note that:

- young people cannot buy alcohol (unless with parental etc. permission) until they are 21 (UK 18, 16 with meals) - and I was ID'd at the age of 67.

- speed limits are typically 5mph lower than the equivalent in the UK

- jaywalking is often illegal. It is never illegal in the UK, apart from on motorways.

On the other hand, US authorities and individuals are often reluctant to interfere in what happens behind closed doors and closed curtains. Perhaps the worst recent example was the failure to inquire into the treatment of the Turpin children who came to public attention in 2018. As one neighbour put it: "We're in California. Everyone's weird. You can't call the police for that. ... People don't want to have community."

But some cities have taken quite drastic action in response to falling child vaccination rates. Anyone living in four areas of Brooklyn in 2019 had to be vaccinated against measles or face a fine of up to £1000. It is hard to imagine a similar law being enacted in the UK, which relies instead on persuasion and public spiritedness - which have the advantage that the do not intensify the militant nature of many anti-vaxers.

Delaware is famous for having very lax company law.

And it is pretty easy to buy and own a gun, so there are around 100 deaths pa per 1 million US citizens (including accidents and suicides). The UK figure is 1. (See Note below for further detail.)

USA over-regulation might be behind signs that the US is over time becoming less entrepreneurial. New Zealand comes first in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Survey, well ahead of both the UK (7th) and the USA (8th).

USA over-regulation might be behind signs that the US is over time becoming less entrepreneurial. New Zealand comes first in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Survey, well ahead of both the UK (7th) and the USA (8th).

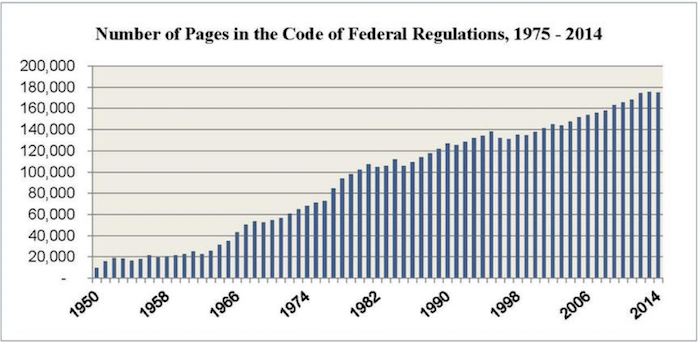

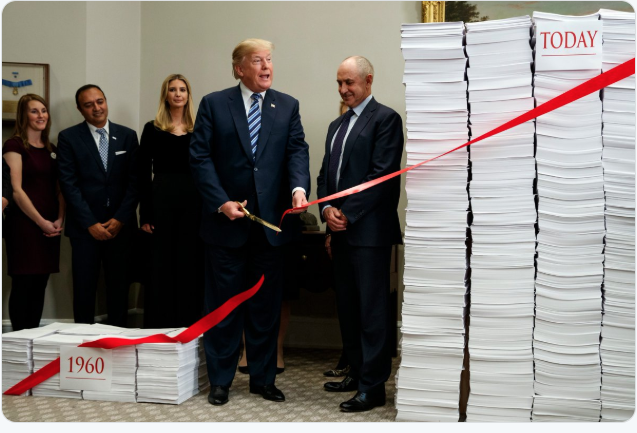

But President Donald Trump vowed to do something about the problem, although critics complained that he claimed credit for the gross cost of the regulations that his administration was shedding, and not deducting the value of those regulations. But much the same criticism was, equally fairly, aimed at the UK's deregulatory efforts - click here for more detail.

Click here to read an interesting opinion piece by Gillian Tett.

Anti-Trust

More positively, Americans were well ahead of the rest of the world in developing what they call anti-trust and we call competition policy. But they are perhaps falling behind Europe, which seems to be taking a stronger line in tackling the problems caused by the Technology Giants. This FT comment provides brief background:

'In the 1980s, when the US, as it does today, felt an economic competitor from the Far East breathing down its neck (Japan then, China now), the federal judge Robert Bork oversaw some hugely consequential changes to American competition and antitrust law. Bork argued that as long as prices for consumers kept falling, the consolidation of large companies into near-monopolies posed no problem for competition.

The problem with the post-Bork competition law that now obtains in the US, Rana Foroohar argues, is that mega-companies today no longer function like their predecessors. "Their products are often cheap or free," she writes, "so consumer prices should not be the measure of competition," In short, the regulatory architecture has failed to keep up with the evolution of what Rana calls the "superstar company".

In a number of sectors, the concentration of market power among a handful of players has had a chilling effect on entrepreneurial energy, with a decline in the number of startups and a discernible, and much-discussed, slowing in the rate of innovation. The clustering of economic power has led to geographical clustering too, with talent and investment being attracted inexorably to a few cities, leaving other parts of the country to wither - with the political effects with which we are now all familiar. '

There were reports in 2020 that European moves to force Google/Android to offer greater choice of search engines to EU customers had caught the attention of Dept of Justice lawyers who were thinking of bringing antitrust charges in the USA.

Follow this link to access a note which compares and contrasts the competition regimes of the EU, the US, India and the UK.

American Companies and European Regulators

I will leave others to explain why, but US corporation s often seem to underestimate European regulators.

One classic case was the European Commission v. Microsoft. The FT's Tobias Buck reported as follow in 2006:-

"Arguably, the negotiations had been bedevilled from the start by a clash of cultures. Microsoft approached the Commission as if theirs was a disagreement between equals. Yet the Commission felt towards Microsoft as a judge towards a thief caught red-handed - the notion of negotiating with the group on level terms was preposterous.

Microsoft's decision to employ tactics similar to those it would have used with suppliers or customers annoyed a regulator charged with defending the public interest. ... DG Comp [felt it] had identifies a problem which Microsoft could choose to resolve by coming forward with a solution. If not, it would be imposed through the imposition of a formal ruling. Since the end would be the same , DG Comp had no preference as to means.

Microsoft was far from the first US group to misread the Brussels regulator. General Electric famously failed to recognise at first that its takeover bid for Honeywell required Commission approval, and later made things worse through its none-too-subtle lobbying tactics."

Regulators' Objectives

I was interested to read the American book Achieving Regulatory Excellence edited by Gary Coglianese. The author of the foreword argues that:

"regulation has a broader societal purpose. At its core, regulation is a human phenomenon. For this reason, regulators should not confine themselves merely to advancing their statutory objectives. We hold a moral and ethical obligation to initiate bold and courageous action to improve the human condition." An author of one of the papers adds that excellent regulators incessantly probe for "strategic macro-opportunities to create public value, potentially by transforming an entire industry, even an entire economy".

This is not a view that would find favour in the UK where most opinion formers believe that (small p) political choices should be made by elected politicians and that the regulatory state may already be far too powerful.

Mainland Europe

It's a gross oversimplification, but there is something in the oft-repeated suggestion that - in countries with a strong Roman Law and/or Napoleonic Code tradition - "nothing is permitted unless it is specifically allowed" whereas - in the UK and USA and Commonwealth countries - "everything is allowed unless it is prohibited".

Be that as it may, there are plenty of (to our eyes) entertaining stories of French, Swiss and German over-regulation. One that caught my eye was a €3,000 fine imposed on a French baker who dared open seven days a week. It is true, of course that UK law restricts many shops' Sunday opening but the French law apparently merely required the baker to close on any one day of his choosing.

Germany

I asked a commercial lawyer in 2017 whether she had seen differences in international regulatory style. Here is her interesting response:

Q. Someone once summarised for me the difference between our law and mainland European law as "In the UK all business activities are allowed unless expressly forbidden. Elsewhere in Europe, all business activities are forbidden unless expressly allowed." Is this broadly true?

A. I don’t think it’s true strictly legally, but it certainly has a lot of truth in terms of approach.

In most countries, regulators aren’t really too interested in us. Every now and again, someone complains and we have to have a chat. That’s about it.

But we do notice that many regulators (sorry for the generalisation!) are perfectly happy to ‘land-grab’ areas outside their technical remit and that can make sense in a lot of circumstances. The cultural differences that I’ve seen are that:

- US regulators generally won’t do this because they fear they’ll IMMEDIATELY be sued;

- British regulators will generally only do it where it makes sense … and …

- Continental European regulators will do it a bit more. There is definitely more of a ‘has the regulator said you can do that?’ (where ‘that’ is outside the scope of the regulator’s power) attitude on the continent than in the UK.

The major exception is Germany. Almost anything we and our competitors try to do is ‘prohibited under German law’. More complicatedly, that’s only half true. The German regulators have stretched their reach further than most of their counterparts but the far bigger effect is that most German lawyers are terribly risk averse and are convinced that the rules go much further than they actually do. We’ve had meetings with partners and the regulator with the regulator saying ‘No, no this is fine. What a good idea, etc.’ and the partner refuses to believe them. They want letters from the regulator saying they won’t intervene before they’ll do anything, even though the regulator has no power to intervene!

And there is a bit of a cultural assumption that the playing field should be leveled to the lowest common denominator and this mean everyone should suffer the burden of everyone else’s regulations.

Doing a deal in Germany can therefore take 3-4 times as long as in the UK and that really can’t be helping them (other than in short-term protectionist sort of way).

Note - Gun Control

This is an area where statistics can be very misleading. The following data was unearthed by the BBC's More or Less team who (sort of) confirmed the counterintuitive claim that mass shootings in the USA are no more common than in countries with much less gun ownership.

This claim is broadly true when FBI-defined mass shootings are compared with those in other countries because countries such as Norway (Anders Breivik), France (The Bataclan) and the UK (Hungerford, Dunblane, Cumbria) also suffer occasional massacres, and their populations are much smaller than that of the USA. However ...

FBI figures exclude 'domestic' and most drug-related gun crime. Using the wider definition, there were 340 mass shootings in the US in 2018 where four or more people were killed excluding the gunman. The FBI definition included only 27.

And the US has a homicide rate of 5.4 per 100k people, compared with 0.2 in the UK. And in 2016, the FBI reported that 71 people had been killed in (their definition of) mass shootings. But there were 14,542 homicides involving firearms.