This web page summarises the main developments in regulation and deregulation from 2021 to date.

UK Regulation after Brexit

How had UK regulation changed since the transition period came to an end on 31 December 2020? Had the UK diverged from EU policy or did continuity prevail? What functions and responsibilities transferred from the EU to UK regulators after 1 January 2021, and were the UK authorities ready? What were the long term prospects for UK alignment or divergence?

Several prestigious institutions joined together to publish the above-named report in early 2021 which took a first step to mapping the new regulatory settlement in the wake of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

Principles of Effective Regulation

This short and sensible PAC report analysed and commented on a number of then current issues including:

- Facilitating innovation,

- Measuring regulatory costs and benefits, and

- Outcomes focused regulation.

But the MPs concluded that government and regulators did not appear equipped to meet the challenges that the report identified.

Loyalty Penalties - Insurance

Loyalty penalties are very annoying and expensive for those consumers who are too lazy or, for all sorts of others reasons, are unwilling or unable to 'shop around for better deals in regulated sectors. But they do encourage competition between providers. No-one, after all, suggests that loss leaders and 'buy one, get one free' (BOGOF) deals should be banned in non-regulated sectors.

Intensive campaigns had already led to Ofgem (somewhat strong-armed by the government) price-capping Single Variable Tariffs (the default tariffs for energy consumers. Then, with effect from early 2022, the Financial Conduct Authority banned tease and squeeze loyalty penalties imposed on consumers renewing their home or motor insurance policies.

Energy Regulation

Ofgem and its predecessors originally had a pretty straightforward mandate - to control the prices charged by the privatised gas and electricity industries. But its duties and responsibilities were increased so often that it became little more (no more?) than a far-from-independent branch of central government. A large part of the story was summarised in a 2018 CCP/UKERC report - see in particular the chart on page 36.

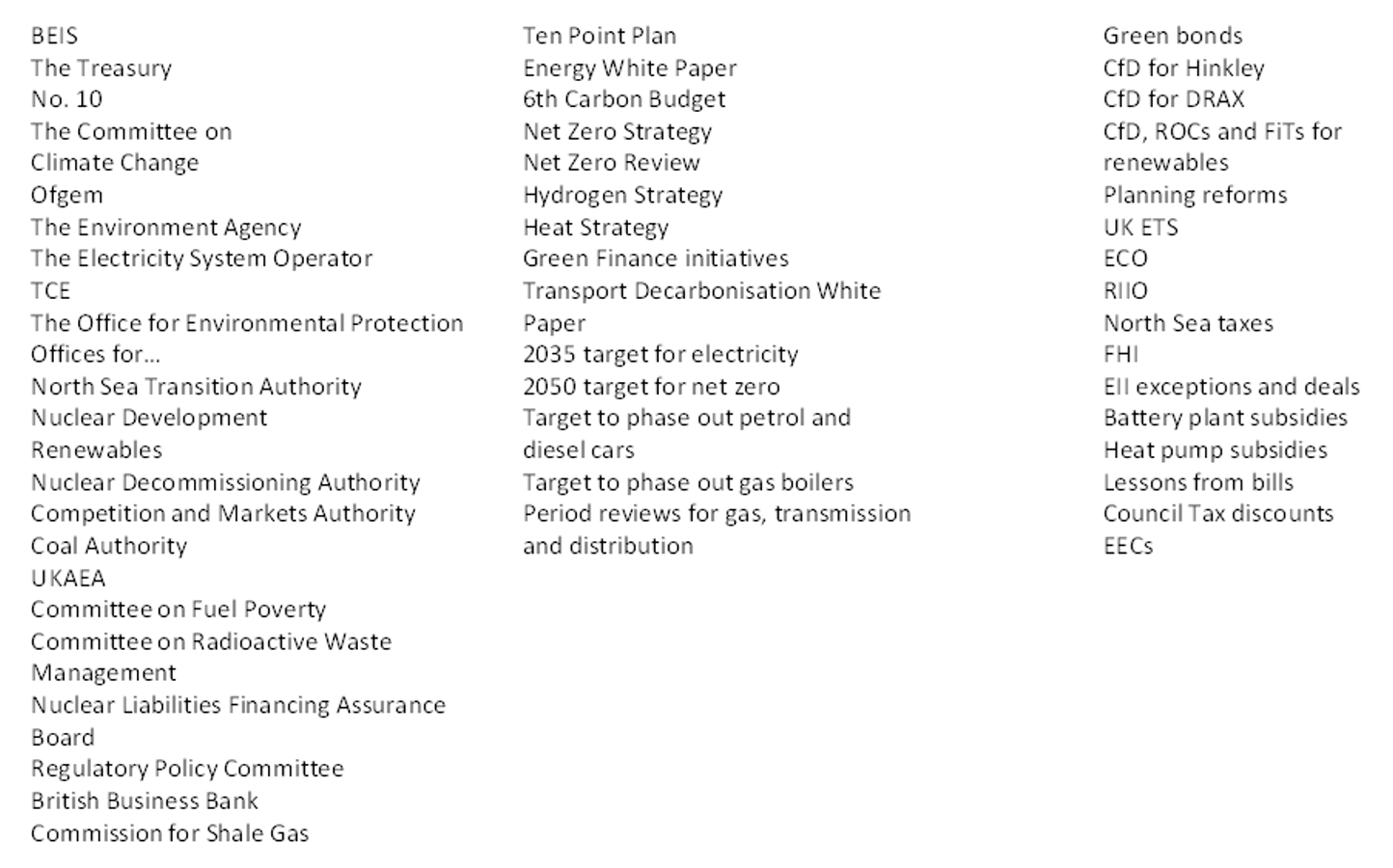

But the situation continued to deteriorate and the resultant madness of UK energy policy was well summarised by Dieter Helm in this 2022 blog, which includes this 'list of all the recent announcements, and all the targets, strategies, Green and White Paper initiatives, the Ten Point Plan, and so on, and all the bodies, organisations, and task forces supposed to implement them'.

MPs concluded, around the same time, that Ofgem's 'negligent' and 'incompetent' encouragement of (obsession with?) competition allowed companies with 'glaringly inadequate financial arrangements and high-risk business models' to enter the market. Their subsequent failure cost around £100 per household. The full report is here.

And all this was before the energy crisis and government interventions following Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Competitiveness & Regulation

Ministers seemed fixated, throughout 2022, on the idea that regulators - and especially financial regulators - should be given an additional objective: encouraging 'competitiveness'. Most economic regulators were already required to encourage competition in their sectors but competitiveness refers to the state of the whole industry so that the FCA, for instance, would be required to help the financial services industry attract business from abroad, which would mean taking part in a race to the bottom - adopting laxer rules and enforcing them less rigorously. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey wryly remarked that 'it didn't end well for anyone" when tried before the 2008 financial crisis.

The EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill

This Bill contained an ultimatum that huge areas of secondary legislation, transferred over from the EU following Brexit, would disappear by the end of 2023 unless ministers acted to save or rewrite it. The hope, as Jill Rutter put it, was that this primal scream of legislation would finally flush the missing Brexit dividends out from the cover of bureaucratic inertia in time to revive the UK economy and convince increasingly sceptical Leave voters that the whole thing had been worth it.

No-one with any knowledge of law or regulation felt that the proposed legislation made any sense at all. The plan to review or repeal all 4000+ pieces of retained EU law by the end of 2023 was accordingly abandoned in May 2023. Here is HMG's formal announcement:

Our Retained EU Law Bill, which is currently passing through parliament, will end the special status of retained EU law (REUL) by the end of 2023 ensuring that, for the first time in a generation, the UK’s statute book will not include reference to the supremacy of EU law or EU legal principles.

We have the unique opportunity to look again at these regulations and decide if they’re right for our economy, if we can scrap them, or if we can reform and improve them and help spur economic growth.

To ensure that Government can focus on delivering more reform of REUL, to a faster timetable, we are amending the REUL Bill to be clear which laws we intend to revoke at the end of this year. This will also provide certainty to business by making clear which regulations will be removed from our statute book.

We will retain the powers that allow us to continue to amend EU laws, so more complex regulation can still be revoked or reformed after proper assessment and consultation.

Ministers could not resist unfairly blaming civil servants for this delay. Further detail is here.

Conformity Assessment Marking

Another very stupid post-Brexit policy was abandoned in July 2023 when the Government announced that they were no longer insisting that the United Kingdom Conformity Assessed (UKCA) system would replace CE [Conformité Européenne] marking for businesses selling goods in the UK. It had previously appeared that UK manufacturers who also wanted to sell in the EU were going to face dual systems of conformity assessment.

Other Brexit Consequences

Meanwhile, much other post-Brexit regulatory policy remained confused.

The government announced in the 2023 Budget that it would use “our Brexit autonomy” in relation to regulating medicines to “move to a different model which will allow rapid, often near automatic sign-off for medicines and technologies already approved by trusted regulators in other parts of the world such as the United States, Europe or Japan”. Chris Grey commented:

That doesn’t mean the end to independent UK medical regulation, and the statement goes on to say that the MHRA will be able to approve some medicines in advance of those other regulators, but it does seem to be a realistic recognition of the ‘regulatory pull’ of larger jurisdictions. Whether it is sensible in terms of medical safety I am not competent to judge, but it is certainly piquant to think that, in the name of “Brexit autonomy”, EU-licensed medicines will be effectively rubber-stamped for use in the UK.

Separately, the EU announced new lower limits for the (anyway minuscule) amount of arsenic allowed in baby food. Chris Grey again:

... the UK trade body for baby food manufacture announced that its members would follow the EU standard, even for products made and sold in Great Britain. This may seem extremely abstruse or esoteric, but it goes to the heart of the entire question of post-Brexit regulatory independence and, with that, the Brexiter idea of sovereignty. For what it illustrates is that, regardless of what UK regulations may be, businesses will adopt the product standard that suits them. That will generally mean, as in this case, the standard that allows them to sell into both markets, which will be the higher standard, and especially the higher standard of the larger market, making the Brexiters’ idea of regulatory sovereignty facile. In some cases, it may mean simply not serving the smaller market at all.

Resources (or rather the lack of them) remained a problem towards the end of 2023. Many regulators did not seem to have the resources necessary to cope with their additional, post-Brexit responsibilities. The MHRA, for instance, was taking two years to license generic medicines.

Crypto ...

... was another area of lively debate by the end of 2022. Many, including me, felt that its dangers were so obvious that regulation should be unnecessary. Legislators and regulators should not try to stop fools becoming parted from their money. And false advertising, fraud and theft were already illegal.

Then, predictably enough, Bitcoin and other currencies lost a huge part of their value whilst investors in various strange businesses found that much or all of their money had disappeared, crypto-currency exchange FTX being one of the most prominent cases.

This was of course the point at which the authorities began to crank up the volume of their warnings and belatedly began to talk about serious regulation. It may come to nothing, of course, and that might be the right answer. But it may be that the blurring of the line between traditional fiance and crypto threatens to harm truly innocent bystanders, whereupon specific regulation might become inevitable.

ChatGPT and other Artificial Intelligence

AI had been around, in various forms, for many years before 2023 but the emergence of easy-to-use large language models (LLMs) caused a paroxysm of concern about their potential dangers. No-one sensible downplayed those dangers, and the best commentators pointed out the need for sensible regulation. Many previous inventions such as the motor car, aircraft and many medicines had the potential to kill lots of people. Their effective regulation, including the need for prior registration and approval, had nevertheless achieved a generally sensible balance between safeguarding the public and encouraging innovation.

The Vallance and McLean Reports

Sir Patrick Vallance's report was published in early 2023 and made several recommendations with a view to encouraging 'pro-innovation' regulation. This was followed in November by a report by his successor as Chief Scientific Adviser, Dame Angela McLean, who made recommendations, in particular, about the Growth Duty which had previously been imposed on many (but not all) regulators.

Who Watches the Watchdogs?

This House of Lords report was published in February 2024. It is an excellent review of all the main issues reflecting regulation - accountability, independence etc. etc. Its own very brief summary of its summary (!) read as follows:

Overall conclusions

When power is delegated to independent regulators, it must be clear what

objectives they are expected to pursue and how these should be prioritised,

which may alter and/or be added to over time. At present, some regulators are

being overloaded and accumulating objectives without clear guidance on how

they should prioritise between them.Similarly, Parliament and the Government should make clear how policy

priorities should be decided, for example on matters of social or economic

policy that may be closer to government decision-making than regulators’

responsibility.If these requirements are met, regulators should then operate with clarity and

predictability, deliver their functions efficiently and be transparently accountable

on clearer terms.Scrutiny by Parliament and its select committees plays a crucial role in holding

regulators and their performance to account. However, lack of resources and the

large number of regulators means that too often scrutiny is reactive to publicity

rather than systematic or timely.To achieve more effective scrutiny, and improved regulatory performance,

further resources and a new ‘Office for Regulatory Performance’ are needed.

It did not seem likely, however, that anyone important would take much notice of the report given the imminent General Election.

Smarter Regulation

There was a broad welcome for the proposals in the 'Smarter Regulation' White Paper published in May 2024. Its proposals to create a regulatory profession and build stronger links between regulators were welcomed by the Institute of Regulation, whilst the Regulatory Policy Committee welcomed the proposed improvements to the scrutiny and quality of regulation.

But the 2024 General Election was announced only a few days later so it remained to be seen whether the next government would take the ideas forward.

The UKCA (UK Conformity Assessed) Mark

Chris Grey reported as follows in September 2024:

Even more farcical, although, paradoxically, at the same time eminently sensible, is the latest retreat from the utter absurdity of the UKCA mark. Here too there has been a long history in delays to the date by which CE (Conformité Européenne) quality marks would cease to be valid, and UKCA would become mandatory. I discussed this issue in detail in August 2023, when the plan was “indefinitely postponed”. However, as I noted then, some products were not included in that, one case being construction products, where CE marks were still due to be phased out by the end of June 2025.

Last week, the government announced that this date would not apply and gave no other in replacement, suggesting that, for these products too, postponement is now indefinite. So far as I know, no such announcement has been made as regards medical devices, the other main area not covered by the 2023 indefinite postponement, with CE marking for these products due to come in by 2028 in some cases and 2030 in others. But I think it is all but inevitable that these will also be dropped.

UKCA was a particularly ludicrous piece of Brexit hubris, which has unravelled because in practice no one wanted it, and the country couldn’t afford it. In that sense, it is a metaphor for Brexit itself, albeit that, unlike Brexit, it proved easy to unravel by simply not doing it. Every time we see the CE mark on a product will serve as a reminder of that.