Deregulation Target set at Zero

2021 began with the government simultaneously tackling the COVID-19 pandemic and the problems caused by the end of the Brexit transition period. It was perhaps therefore no surprise that it announced that it did not intend to cut overall regulatory burdens on business over the current parliament, pending a review.

Regulatory Policy Committee gives evidence to the House of Lords’ Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee

Stephen Gibson (Chair of the RPC) and Andrew Williams Fry (member of the RPC) gave evidence to the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee (SLSC) in the Palace of Westminster on Tuesday 5 April. They were asked about the RPC’s work, how the current Better Regulation system is operating and what they would like to see from the reforms the Government is currently considering. Here are extracts from their report of the meeting:

They explained that the RPC sees its role as helping to improve the analysis conducted across government to ensure that both ministers and Parliament have the best possible evidence on which to base regulatory decisions. They also explained the RPC’s approach of issuing ‘initial review notices’ which give departments an opportunity to improve impact assessments (IAs) during the scrutiny process. The fact that a significant number of IAs are improved during the course of RPC scrutiny is a positive feature of the process and shows the value that independent external scrutiny can add.

A frustration with the current system was the increasing number of IAs received very late in the process and with requests for expedited scrutiny. This makes it harder for RPC input to be taken on board. For this reason, Stephen explained that the RPC is supportive of the Government’s intention to have mandatory scrutiny earlier in the process.

They also discussed the fact that the RPC currently sees fewer post-implementation reviews (PIRs) than expected. PIRs are a critical step in the policy-making process – checking whether regulation is having its intended effect and should be retained, or whether it should be amended, replaced or revoked.

Scrutiny, ahead of implementation, of plans for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of regulation, and a better process for tracking when PIRs should be produced, could both help to ensure that regulation is as effective as possible while minimising negative impacts.

Stephen argued that, while the current approach has value in ensuring that government considers the impacts of individual regulatory proposals on business and civil society organisations , there is little evidence that the current Business Impact Target (BIT) had been successful in making government focus on overall reductions in the burdens of regulation on business. For that reason, the RPC was supportive of the Government’s intention to reform the BIT.

Stephen set out what the RPC would like to see in the reformed Better Regulation Framework and that it was important that some of the benefits of the current framework - such as requiring RPC review of final stage IAs to support effective Parliamentary scrutiny of government proposals - are not lost when designing a new framework.

Brexit Opportunities

The Prime Minister was reported to have asked business leaders, in a conference call, for deregulatory suggestions that could be presented as a Brexit dividend. "A government source" talked about "the UK becoming a low tax, low regulation regime like Singapore". Other ministers were also reported to have made similar requests in the first months of 2021.

The Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform, chaired by Iain Duncan Smith, was announced in February 2021 and posed pretty much the same question. It was asked to report in April.

It was reported in February 2021 that Chancellor Rishi Sunak was to chair a new Better Regulation Committee to 'help stimulate growth, innovation and competition in the UK, while attracting new investment, enabling businesses to grow dynamically, and maintaining the high standards the UK has consistently championed in areas like workers’ rights'.

Those not involved were half-amused, half-angry that a government that had championed the benefits of Brexit could not immediately identify what it wanted to do with its new freedom. Giles Wilkes encapsulated many observers' reactions in these tweets:

It's always the same. Someone chunters on about how what we need for growth is regulatory change. But they're not sure what. So they issue a plea to business/the public. It's like asking someone else to provide the punchline to your own stupid joke

My *first day* as a spad, a well known business organisation slaps down on my desk a list of 100 regulatory problems from members. Hooray, I think: actual content. Leafing through - about 98 were variants on "I find it tiresome having to make arrangements for pregnant staff"

It was announced in May 2021 that Cabinet Office Minister Lord (David) Frost, who had negotiated the Brexit agreement, was recruiting the Head of new Cabinet Office unit to explore 'Brexit opportunities' particularly around shedding EU regulations.

The press were briefed in February 2022 that Ministers were closing in on a deal with City watchdogs to unleash what Prime Minister Johnson called an 'investment big bang'. They wanted in particular to reform the insurance industry's Solvency II rules in the hope that this would allow insurance companies to invest much more in infrastructure, including green energy projects. But Ministers failed to acknowledge that the EU had announced its own review of the rules in September 2021 so the UK was playing catch up, and was not likely to be able to claim that any deregulation had been greatly facilitated by Brexit.

The Government's Benefits of Brexit paper killed off the possibility of resurrecting anything like the 'one in, two out' system of deregulation. 'While there are many benefits to such a rule ... we do not think it consistent with delivering world-class regulation to support the economy in adapting to a new wave of technological revolution or to achieving net zero.'

Jacob Rees-Mogg was appointed Brexit Opportunities Minister in February 2022 and was, we were told, ordered to come up with 1,000 EU rules to scrap. He in turn asked members of the public to come up with ideas, including via a prominent story in the Sun. It remained unclear why this exercise was necessary, given that Brexiteers might have been expected to have lots of ideas even before the 2016 referendum, and certainly afterwards.

Nick Tyrone summarised Mr Rees-Mogg's conundrum in this way:

Anyhow, it’s worth gazing into a crystal ball and wondering what will happen under Rees-Mogg’s reign as Brexit Opportunities Minister. I reckon he’ll do what everyone who has tried to solve this conundrum has done before. He’ll ask businesses and get next to nothing back. They don’t really want to change much. Then he’ll figure he needs to speak to small businesses, only to find that’s really logistically difficult and besides, they don’t actually want to change much either, convinced that whatever the government does will almost certainly make things worse. Then the stuff he’ll find using Brexity think tank types will all be about the slashing of workers rights, getting rid of construction safeguards, that type of thing, which will just be rejected by whomever is the prime minister out of hand, or will meet with such opposition from campaign groups and the public that it will all be dropped. In the end, Rees-Mogg will come up as empty handed as everyone else who has attempted the same exercise.

Here’s what I’ll close this section on: the whole idea of having a Brexit Opportunities Minister is an indictment of Brexit itself. If Brexit had been a good idea, the opportunities would be so obvious, every government department would be up to their eyeballs in them already. The fact that six years on from the referendum, this needs a whole extra minister tells you everything you need to know.

The FT's Peter Foster summarised the state of play, as at mid-May 2022, as follows (emphasis added):

To date it is the external effects of Brexit that attract the most attention — threats of trade wars over Northern Ireland, for example, or the hit to UK trade figures — but in the long run it is the internal changes to the UK wrought by Brexit that are likely to count the most.

The government has promised a Brexit Freedoms Bill that will give the UK government the freedom to quickly repeal elements of “retained” EU law that were subsumed into the UK statute book at the point of EU exit.

Brexiters hope this will light the touchpaper on the long-promised “bonfire of EU red tape”, firing up a nimbler, more competitive UK that is better able to attract investment and grow its economy freed from the suffocatingly legalistic approach of Brussels.

Two stories this week, lost in the hullabaloo over Northern Ireland, have provided some early pointers as to how this will play out under Boris Johnson’s government and raised genuine questions about how easy it will be to realise the promised Brexit dividend.

The first was a report from the National Audit Office, which found that three UK regulators — the Competition and Markets Authority, the Health and Safety Executive and the Food Standards Agency — are struggling to tool up for the brave new post-Brexit world.

This isn’t that surprising. As the NAO found, having spent 40 years outsourcing the policing of much regulation to the EU, building replacement UK capacity overnight is not easy.

There is a shortage of professional expertise, for example veterinarians and toxicologists (for testing food), which then has the knock-on effect of regulators having to spend large amounts of time and money training their own staff (remarkable to discover that a quarter of all staff time in HSE’s chemicals division has been spent on training).

This has opportunity costs (the HSE won’t be fully stood up for Brexit duties for another four years) but also actual costs, both for the regulator (hiring new staff, building new processes) and for businesses wrestling with new regulatory regimes.

In the longer term Brexiters’ believe the regulatory revolution will bear fruit for the UK economy despite the short term difficulties.

But that brings us to the second — and arguably much more important — piece of the post-Brexit regulatory puzzle, which is whether the government has a clear idea of what regime it is trying to build, and to what end?

We now have a new minister for Brexit opportunities in the shape of Jacob Rees-Mogg, who has set up a unit to ask all UK government organisations to review “retained” EU legislation with a view to making amendments to it.

But as the NAO report says: “It is not clear when the unit will complete its review, or what action it will then take or suggest to departments.”

Such uncertainty is a natural consequence of shifting to a new regime, but across the board industries from cars to chemicals are craving clarity and (in many cases) continuity with EU standards in order to minimise future costs.

This is where the government’s ideological commitment to divergence from EU law often trumps commercial or practical considerations from the end users of the regulations.

Mogg has already said he is determined that the UK should stop looking over its shoulder at EU regulation. Yet at the CBI annual dinner this week I lost count of the number of business chiefs sighing in frustration at the UK government’s desire to “free” them from EU-derived rules and regulations (data, cars, chemicals, environmental etc) that are fundamental to their supply chains and exporting ambitions.

The chemical industry is still waiting for details of how the UK REACH chemicals safety regime is going to operate; just as the auto industry awaits if the UK will follow new EU car safety rules, as it obviously should given the integrated nature of EU and UK car making.

By the same token, the UKCA mark — an equivalent of the EU’s CE mark — is still due to come into force on January 1 2023, but groups such as the Construction Products Association are also clear that a divergent standards regime between the EU and UK would be costly and counterproductive (meaningless cost-neutral duplication they can learn to live with).

This is not, it is fair to say, what Brexiter ministers like Rees-Mogg want to hear, believing that this is industry cleaving to the status quo, failing to embrace the future opportunities that come from smarter, lighter-touch regulation — even if these have yet to be defined.

The gap between ideology and pragmatism was clearly visible in a second story this week, where a comprehensive list of environmental and marine industry groups rubbished George Eustice’s proposals to “streamline” UK conservation law, which is still based on the EU habitats directive and other bits of retained EU law.

Figures representing more than 70 conservation and trade groups were absolutely clear the Eustice reforms would be counterproductive and costly. As Richard Benwell of Countryside Link put it, they would “shake the foundations of environmental law” in England, “with no evidence that it would improve the state of our struggling wildlife sites”.

There is no sign that Eustice — who was promising during the 2016 referendum campaign that to sweep away what he called “spirit-crushing” EU laws — is going to step back, despite the strength and breadth of expert opposition.

As the NAO observed, a clear picture of government intention is still to emerge, but there are some early signs that a deregulatory agenda is being pushed through.

This week, to little fanfare, the government published its environmental principles, which green groups said would “weaken vital protections for environment and public health” as they shift the UK to a more US-style “risk-based” approach.

In moving away from the “precautionary principle” used in EU lawmaking, the effect, says Ruth Chambers from the Greener UK coalition, will be to “water down common sense rules that protect nature”.

The government must balance economic and environmental concerns. It claims that its environmental ambitions and targets, such as halting species decline by 2030, are some of the toughest in the world.

Ministers point to the fact that the Environment Act 2021 mandates them not to reduce existing protections, and yet the effectiveness of that safeguard rests on whether a minister “is satisfied” that new rules and regulations don’t, in fact, do this.

So in practice, what are presented as cast-iron legal guarantees to protect the environment are actually — when placed under the microscope — what one environmental NGO boss calls “subjective legal tests” that will be very difficult to challenge. Ministers get to write their own tickets.

At this stage, it is just too early to say whether the government’s deregulatory agenda is something coherent, or something more piecemeal and ad hoc, driven by individual departments and ministers, such as Eustice and Rees-Mogg.

In any event, out of the current fog regulators must hope that (to quote the NAO) “a clear line of sight” emerges sooner rather than later, linking “high-level and statutory objectives to detailed operational objectives, plans and priorities”.

Otherwise more money will be spent in error; more opportunities will be lost.

The deregulatory ideas emerging from the consultation in the Sun and elsewhere were reported a few weeks later. None of the ideas were inherently ridiculous although they would all roll back various protections which were presumably once seen by many to be necessary. Chris Grey commented that 'Almost without exception they are things which don’t require Brexit or are trivial, or both, and very likely nothing will come of them anyway. In that sense, the very call for suggestions can itself be regarded as symbolic of ‘listening to the people’ or, alternatively, of how bereft of ideas the Brexiters in general, and Rees-Mogg in particular, actually are.'

Here is the report in the Daily Express - but note that these are 'nine of the top ideas' (chosen by Mr Rees Mogg's department). They were not necessarily the nine most popular:-

'Nine of the top ideas named from the department are:

1. Encourage fracking, shortcut rules on planning consultation via emergency act.

2. Abolish the EU regulations that restrict vacuum cleaner power to 1400 watts.

3. Remove precautionary principle restrictions (for instance) on early use of experimental treatments for seriously ill patients and GM crops.

4. Abolish rules around the size of vans that need an operator's licence.

5. Abolish EU limits on electrical power levels of electrically assisted pedal cycles.

6. Allow certain medical professionals, such as pharmacists and paramedics, to qualify in three years.

7. Remove requirements for agency workers to have all the attributes of a permanent employee.

8. Simplify the calculation of holiday pay to make it easier for businesses to operate.

9. Reduce requirements for businesses to conduct fixed wire testing and portable application testing.'

Mr Rees Mogg also announced that the forthcoming 'Brexit Freedoms Bill' would introduce a five year expiry date ('sunset clauses') for 1,500 pieces of EU legislation so as to force his ministerial colleagues to think seriously about whether they needed to be retained, amended or withdrawn. Although there is much to be said for some sunset clauses, this blanket approach looked like causing significant problems for the ministers and officials who will be carrying out the (1500 simultaneous?) consultations - and for their consultees.

He doubled down on this announcement a few weeks alter when he announced a 'dashboard' (a new website) listing 2,400 pieces of retained EU law and invited the public to pick those they would repeal. The official Cabinet Office announcement was a little more restrained:-

In September 2021, Lord Frost announced the review into the substance of retained EU law (REUL) to determine which departments, policy areas and sectors of the economy contain the most REUL.

Today, the Rt Hon Jacob Rees-Mogg, the Minister for Brexit Opportunities and Government Efficiency, publishes the outcome of this review, which is an authoritative catalogue of REUL. The Minister invites the public to view this catalogue so that the public is aware of where EU-derived legislation sits on the statute book and is able to scrutinise it.

Now that we have taken back control of our statute book, we will work to update it by amending, repealing or replacing REUL that is no longer fit for the UK. This will allow us to create a new pro-growth, high standards regulatory framework that gives businesses the confidence to innovate, invest and create jobs, transforming the UK into the best regulated economy in the world.

In terms of next steps, we will bring forward the Brexit Freedoms Bill, as announced in the Queen’s Speech, to make it easier to amend, repeal or replace REUL to deliver the UK’s regulatory, economic and environmental priorities.

Alongside the Bill, government will continue to engage with stakeholders to identify where we can maximise the benefits of Brexit and test opportunities for reform, from artificial intelligence and data protection, to the future of transport and health and safety. Any future reforms will prioritise making a tangible difference to improving people’s lives in the UK.

... [But the public should] use the normal correspondence channels to highlight any specific regulations they would like to see amended, repealed or replaced.

Regulatory Policy Committee

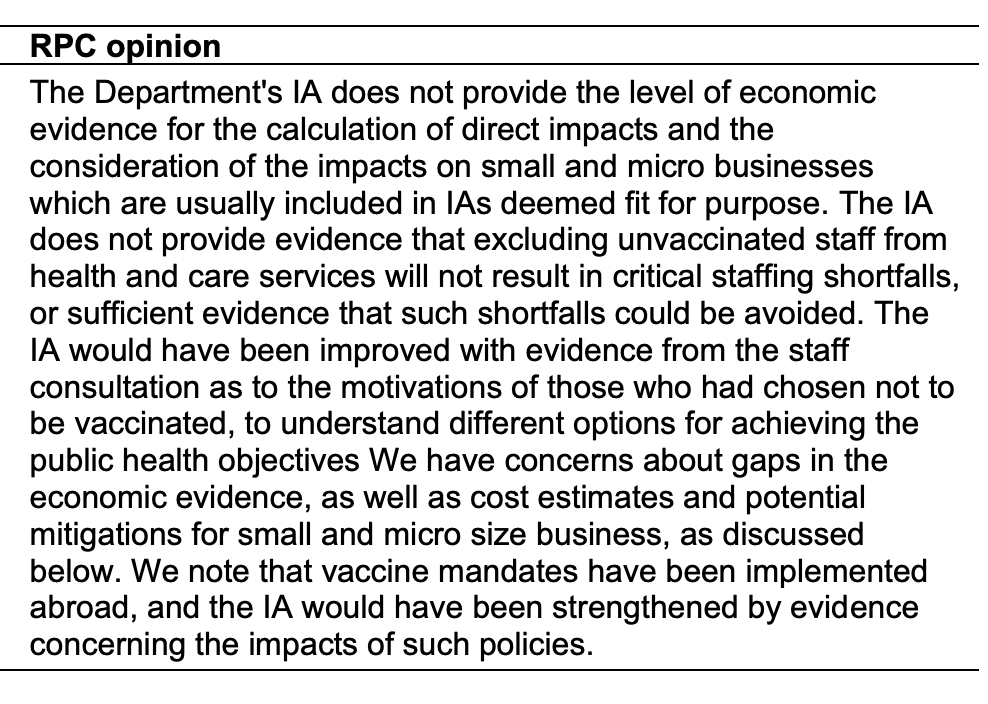

This committee carried on doing very good work scrutinising key regulatory proposals. I particularly admired its demolition of Ministers' well intentioned but flawed decision to require all NHS staff to be vaccinated against Covid. The Department of Health pressed on with the plan but eventually backed down, partly because too many staff remained unvaccinated (so their dismissal would have caused great disruption) and partly because the strength of the pandemic seemed to be waning.

The RPC then, in early 2023, condemned the impact assessment of the government's draft anti-strike legislation which mandated minimum service levels. It declared the cost-benefit analysis as weak and 'not fit for purpose'. Sources of evidence were 10 years old and assumptions had been made without appropriate evidence and analysis. Although the impact assessment listed similar policies in other countries, it failed to include details of the minimum service levels or their effectiveness.

Reforming the Framework for Better Regulation

This initially serious and substantial consultation exercise was launched in July 2021. The Government's response to the consultation was (unfortunately) included only in the February 2022 "The Benefits of Brexit" policy paper - see pp 20-29. This Brexit branding, followed by the turmoil surrounding Boris Johnson's premiership, meant that there seemed little prospect that the (anyway vague) policy decisions would lead to significant change.

Anyway, for what it is worth, officials said that the paper announced "four core policy changes that aim to improve and control the flow of regulation across government, and assess its value:

- Adopting a greater emphasis on proportionality, to ensure that we regulate in a way that focuses on allowing businesses to grow, while giving greater flexibility to try innovative new approaches.

- Ensuring that we are making the best use of alternatives to regulation by introducing an earlier scrutiny point at which departments will be asked to justify their decision to regulate.

- Improving how we evaluate regulation, including post-implementation reviews.

- Improving how we measure the overall impact of regulation, including consideration of a more holistic approach and the removal of the Business Impact Target in its current form."

Officials also told contributors to the consultation that

"While these reforms represent a streamlining of process and a change of emphasis, they do not undermine or reduce the requirements for departments to produce options appraisals and quantified impacts in accordance with the HMT Green Book. The Government’s reforms to the framework for better regulation are supported by policy changes, that aim to deliver on the Government’s key priorities and improve the quality, flow and assessment of regulation.

The reforms proposed to the framework for better regulation will not take place at once. There will be a transitional year, where we finalise the details underpinning the reforms."

The Brexit document accordingly signalled an intention to remove the Business Impact Target in its current form and to remove the 'Independent Verification' role of the Regulatory Policy Committee, presumably because the RPC's scrutiny was becoming embarrassing - see above. The removal of the BIT was welcomed by just about everyone that knew anything about it, including the RPC and unchecked.

Liz Truss becomes Prime Minister

Liz Truss's accession in September 2022 provided an obvious opportunity to try to breath some life into the search for a Brexit regulatory dividend. Peter Foster again provided a helpful commentary a couple of days later:

Slightly less encouraging this week was Kwasi Kwarteng, the UK’s new chancellor, telling financial services bosses he wants a “Big Bang 2.0” in the City, driven by a post-Brexit overhaul of regulation to boost the sector’s competitiveness. Deregulating the City might, potentially, hold a Brexit dividend but the sluggish record on delivery thus far speaks to the fact that a global industry, like finance, wants first and foremost a stable and predictable regulatory environment. Ultimately, setting up a public fight between ‘go-getting’ chancellor and reluctant regulator and City interests is actually more likely to leave these longed-for dividends stuck in the realm of the rhetorical — like so many of the post-Brexit promises of the Johnson era.

At the heart of this problem is that the politics is driven by the Tory myth that regulation, or ‘red tape’, is a stultifying and parochial force rather than — as is often the case — a fundamentally enabling and globalising one.

Take cars. The UK car industry exports 80 per cent of its output, half of which goes to the EU, and therefore relies on following global regulatory standards in order to access markets and keep down costs. After Brexit, the UK government remains committed to creating its own regulatory regime — so called type approvals — for vehicles entering the UK market, but last week once again delayed the introduction of the compulsory UK scheme, under pressure from industry. The message is that building your own regime takes time, requires bureaucratic bandwidth and resources for very uncertain gain.

At the same time, the EU has introduced its second European General Safety Regulation (GSR2) which includes requirements for new safety technologies, that send Brexiters into fits of apoplexy about EU nanny statism. Jacob Rees-Mogg has been happy to indulge this in the recent past, suggesting British cars will be free to ignore such technologies, but the assumption in industry is that the government will adopt the majority of these standards and is unlikely to ban the rest from being fitted to UK vehicles. That's because it's not economic to make UK cars to different standards and also, presumably, because it's not a good political look to argue that British cars should be less safe than European ones.

The point is that these rhetorical red-herrings distract from where the UK industry might actually steal a narrow advantage, for example by having a lighter-touch regulatory regime around testing autonomous vehicles and sharing the data generated by them. But such gains — like most productivity boosts — will be incremental and won't happen overnight, not least because the UK government is not expected to have passed legislation allowing it to change existing EU law until the end of next year at the earliest.

And as David Bailey, professor of business economics at the Birmingham Business School, observes whatever the upside of UK divergence, its scope will always be constrained by the market size and the gravitational regulatory pull of the EU market.

That doesn't mean the benefits of Brexit aren't worth aiming for, but the reality is that such benefits will not be found by considering UK industry in isolation from the economic neighbourhood.

The sooner, therefore, that the rhetorical dial shifts away from demanding divergence for divergence sake, and moves back towards delivering upside for industries, like autos, whose economics are hard-wired into the European market, the quicker those longed-for productivity gains will materialise.

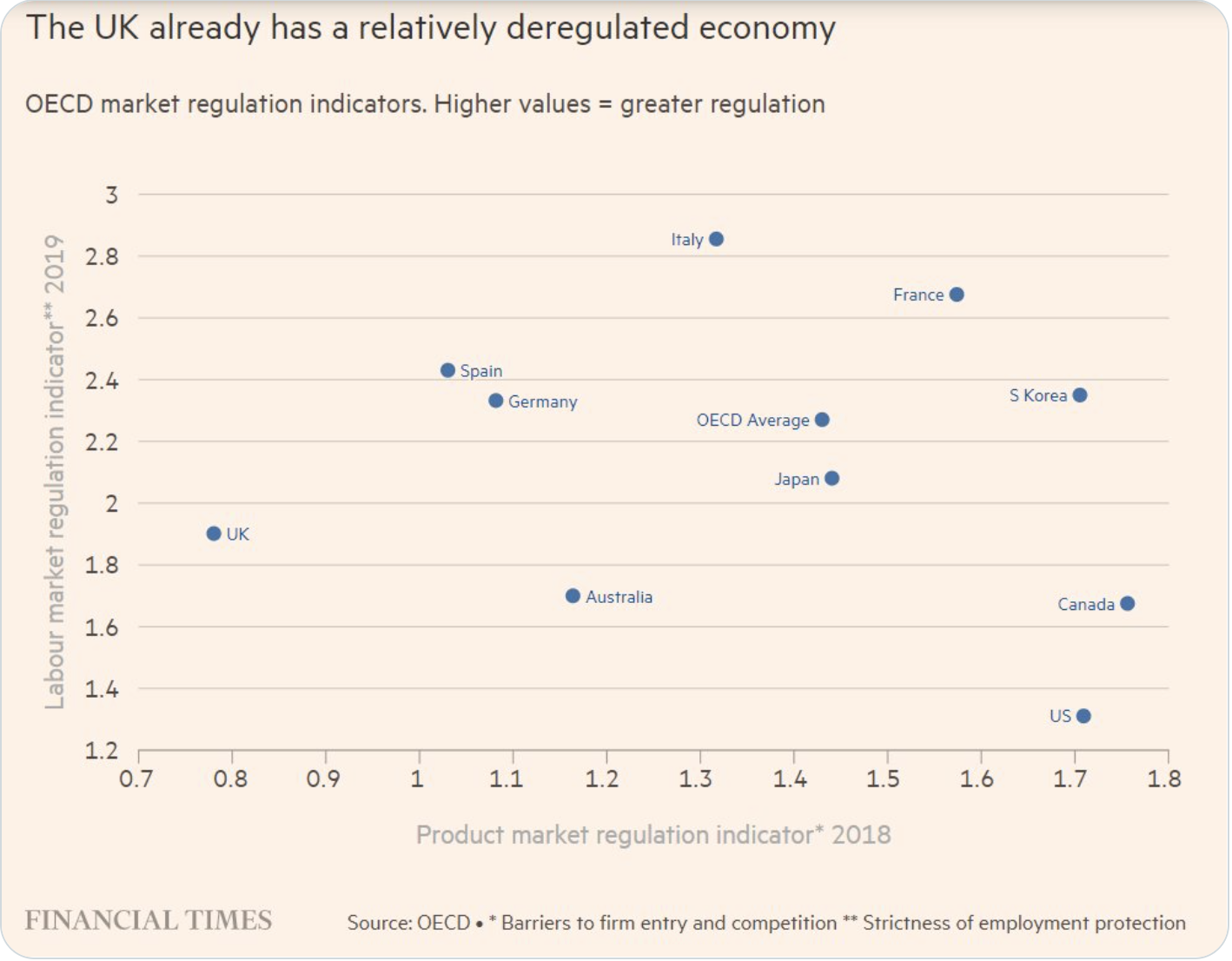

The other problem facing deregulatory zealots, as many pointed out, was that the UK was already lightly regulated compared with many other advanced economies so it might prove difficult to do a lot more. This OECD chart summarised the broad picture pretty well - though note that the axes do not begin at '0.0'.

Cumulation

But some industries experienced almost insane and intolerable regulation, generating large fees for its consultants and experts. One house builder reported that (in order to build 350 houses in Staffordshire) he had to provide:

- a statement of community involvement

- a topographical survey,

- an archaeological report,

- an ecology appraisal,

- a newt survey,

- a bat survey,

- a barn owl survey,

- a geotechnical investigation (to determine of the ground was contaminated)

- a landscape and visual impact assessment,

- a tree survey,

- a development framework plan,

- a transport statement,

- a design and access statement,

- a noise assessment,

- an air quality assessment,

- a flood risk assessment,

- a health risk assessment, and

- an education impacts report.

Small Business Definition Increased from 250 to 500.

The new Liz Truss-led Government announced in October 2022 that:

"Thousands of the UK’s fastest-growing businesses will be released from reporting requirements and other regulations in the future, as part of plans aimed at boosting productivity and supercharging growth. ... Regulatory exemptions are often granted for SMEs, which the EU defines as below 250 employees. However, we are free to take our own approach and exempt more businesses to those with under 500 employees. (sic) We will also be able to apply this to retained EU law currently under review, which we would not have been able to do without our exit from the EU.

The changed threshold will apply ... to all new regulations under development as well as those under current and future review, including retained EU laws. The Government will also look at plans to consult in the future on potentially extending the threshold to businesses with 1000 employees, once the impact on the current extension is known.

The exemption will be applied in a proportionate way to ensure workers’ rights and other standards will be protected, while at the same time reducing the burden for growing businesses."

This was a long way short of "making sure that no business under 500 employees gets subject to business regulation" as announced the previous day by one over-excited minister.

Rishi Sunak becomes Prime Minister

It was hoped that Mr Sunak would have a more sensible approach to regulation than his three predecessors. As it was now 6 years since the Brexit referendum, Ministers' attention would ideally switch from the over-simplistic drive to 'slash red tape' and they might instead focus on new fields such as gene editing, cryptocurrency and AI where incremental improvements might be made within a bespoke UK regulatory system designed for a single country rather than needing to cater for a community of 27 countries.

One small sign of encroaching sanity was the new administration's decision to postpone, yet again, the nonsense of the new UKCA product safety mark. The original implementation date had been January 2022. The new target date was changed from January 2023 to January 2025.

But it pressed on with its Retained EU Law Bill which would will see all retained EU law disappear in December 2023, unless the government decided to produce new and equivalent UK laws. The RPC gave it is lowest possible score (unfit for purpose) saying that ministers 'had not sufficiently considered, or sought to quantify, the full impacts of the Bill [nor considered] the impact on small and micro businesses'.

Impact Assessments

A House of Lords report in late 2022 laid bare the continuing failure of departments to produce decent impact assessments:

'One of our major concerns is that IAs which are published late, or that appear to have been scrambled together at the last minute to justify a decision already taken, may undermine the quality of the policy choices that underpin the legislation.

'The IA rule book is good but it is ineffective if no one imposes discipline when its provisions are not followed.

If Parliament is to perform its critical function of holding the Government to account, it is of paramount importance that the two Houses are given complete and comprehensive information about the basis on which policy choices are made and the reasons why alternative options have been rejected. We cannot perform that role without the right information at the right time.

As so often with Governments around this time, there was no sign that Ministers were even slightly concern about such Parliamentary criticism.

EU Retained Law & Gold-Plating

Nick Tyrone, the former Director General of the Red Tape Initiative published a very readable blog in November 2022 explaining why getting rid of EU retained law was 'a massive red herring' and why gold-plating had never been a big problem.

Subsequent developments are summarised here.