Much modern policy making is based on the assumption that it is generally a good thing if businesses, universities, schools and hospitals compete hard with each other. It encourages what Joseph Shumpeter called 'a perennial gale of creative destruction', encouraging the efficient allocation of resources, forcing individual organisations to be efficient and innovative and to meet the needs of their customers, students and patients. This efficiency and innovation together ensure that choice is maximised, novel products come to market as soon as possible, and prices and service standards meet the needs of most customers.

Other types of economic organisation, including central planning, can sustain growth for a period but most new goods and services would not become available without market capitalism - as was evidenced by the catastrophic failure of communist planned economies by 1989.

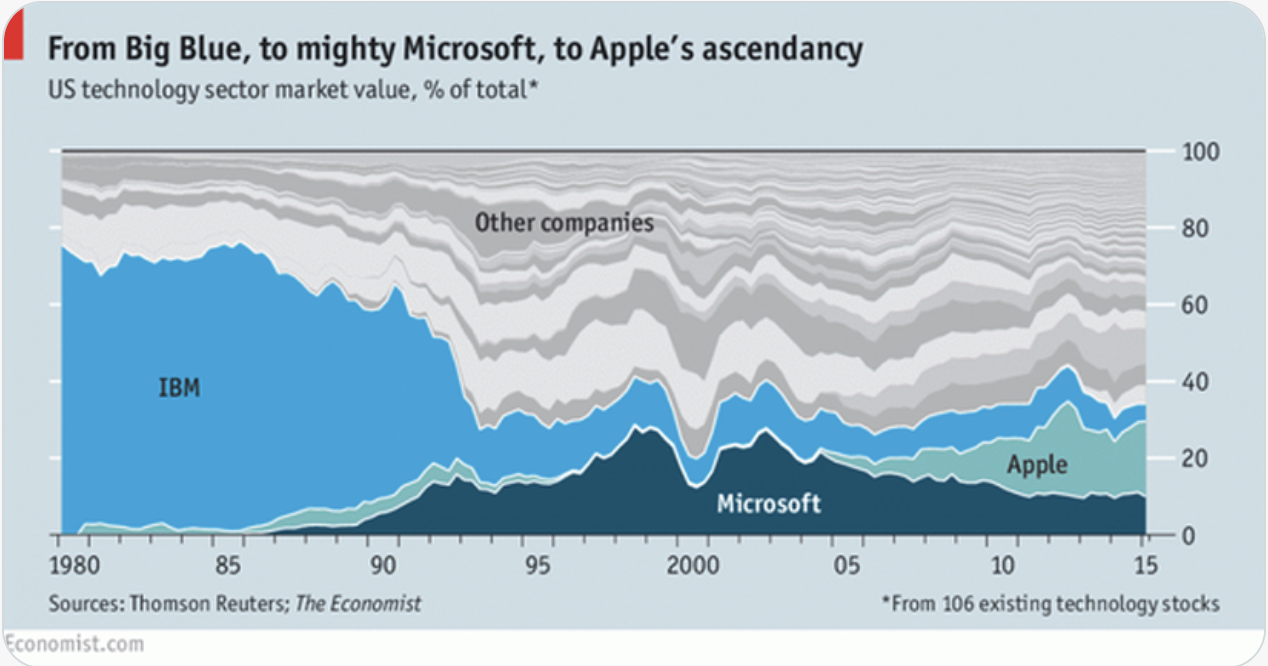

This chart shows how competition and competition policy first helped defeat dominant IBM, and then dominant Microsoft.

The consequences of competition in information technology played out over years, decades even. But competition can work surprisingly quickly. Once the Barcelona-Madrid high speed railway was opened up to competition, passenger numbers increased by 50% and fares fell 49% over a period measured in months, not years.

Competition is also good for suppliers and workers. The former need to be able to sell to companies that are innovative and thriving; both need to be able to seek other buyers or employers if dissatisfied with the way they are being treated. And the choices made by large numbers of citizens are usually much better than decisions made by politicians or bureaucrats when it comes to the allocation of scarce resources. To misquote Churchill:- Markets are the worst form of asset allocation - apart from all the others.

There is also the point that markets don't pass judgment on the preferences they satisfy. Markets don't wag fingers. This is quite liberating.

Last - but far from least - competition benefits everyone by encouraging continuous economic growth.

Stephanie Flanders, reviewing a book by Tim Harford, summarised the virtues of competition in this way:

Why do economists like markets? ... Because, as Harford, explains, when a market is freely operating, everyone is forced to tell the truth. ... In a perfectly efficient market, the coffee shop can’t lie about how much it cost them to make your coffee, because there would soon be a competitor next door selling it for less. And I can’t pretend I don’t really want that tall decaf latte I ordered, because the fact that I was willing to pay £3.50 for it showed the world I wanted it rather a lot. The result is that the right things are made in the right quantities and they go to the people who value them most. This is the idea of a perfectly efficient market, in which neither buyers nor sellers have any market power and lots of other crazy conditions are met, which critics rightly point out bear little relation to the real world. But Harford is good at showing why the efficient market story is still a useful one, and why rejecting markets has a cost.

But ... competition can lead to inefficient allocation of resources.

This is particularly obvious in the case of transport where it can make a good deal of sense for operators to cooperate. It is very difficult, for instance, to travel north/south across London, Manchester and Glasgow because competing railway companies saw no point in joining their networks beyond their terminal stations at Victoria, Waterloo, Euston and Kings Cross, for instance.

The multitude of competing lines around central London did, however, offer considerable resilience when they were bombed during the Second World War.

And ... competition favours those with sharp elbows:- those who can shop around and force themselves to the front of the queue for excellent education and healthcare. This group does not include the poor, vulnerable and other disadvantaged.

Some young people begin adult life after an expensive education, with economic security and sometimes an inheritance or lots seed money to start their first business. Michael Sandel, in What Money Can't Buy, points out that inequalities of wealth and income wouldn't matter very much if all they led to was the ability to buy yachts, sports cars and fancy vacations. But as money has comes to buy more and more - political influence, good medical care, a home in a safe neighbourhood, access to elite schools - the distribution of income and wealth looms larger and larger.

Mr Sandel also points out that market reasoning tends to empty public life of moral argument. It is one thing to allow fast tracks at Disneyland. But private health care can start to shunt everyone else into long waiting lists. Ticket resale sites - and selling TV rights to major sports - can change the character of what would otherwise be important social events. There have been calls for tradeable procreation permits, and much stronger calls for tradeable pollution permits and carbon trading which allow wealthier folk to bribe poorer people to make unattractive sacrifices.

Competition and markets can therefore sometimes make the community feel less cohesive - and a better place to be a consumer than a worker. Politicians who fail to recognise this may encounter a backlash.

So what does this mean for competition policy?

First, let's recognise that it is necessary for the state to allocate scarce resources when the country is at war - or when there is a severe shortage - of housing, for instance. That is why the market economy was rapidly abandoned at the beginning of both World Wars - and it took thirty or forty years from 1945 before most of the World War 2 cartels, restrictive practices and monopolies were abandoned.

And there are examples of countries thriving whilst - and some would argue by - encouraging cartels. Germany's economy grew rapidly in the late 1800s whilst its government encouraged companies to coordinate their prices, production levels and marketing. The Germans believed that this helped achieve economies of scale, remove damaging competition and facilitate R&D and investment. There were 366 officially recognised cartels in 1905, and whole areas of German industry had been cartelised.

There is a related debate about whether the state should support industrial national champions at the expense of local or international competitors. Such policies seem to have worked quite well - for a while at least - when implemented by countries with strong dirigiste traditions - i.e. where (a) large companies are willing to accept guidance from central government, (b) the government's policies remain very stable over a long period, and (c) the companies' managements and workforce are ambitious in terms of investment, improving workforce productivity, and marketing effort - especially in export markets. South Korea's Chaebols and Japanese Keiretsu come to mind as examples of countries where these factors have existed and national champions have thrived - for a time. These prior conditions have not, however, often been met in the UK where national champions have all too often failed, mainly because their managements and workforces have sought a quiet life, sheltered from competition and cocooned by the support from central government.

There are pretty clear signs, too, that dirigisme is no longer working as well as it used to in France and Japan, perhaps because modern markets are less stable, and innovation is speeding up.

Follow this link to read more about the national champions debate.

Outside the above special circumstances, competition (like democracy) is far from perfect, but it is often the least bad of all the alternatives that have been tried. Put another way, the good thing about competition is that it isn't monopoly! The key attribute of a monopoly is that it confers freedom from challenge. This makes life comfortable for owners, managers and staff. But it weakens performance incentives and it weakens the pressure to innovate and try new ideas, allowing organisations to stick to routines and inefficient practices which ought to be abandoned. The chart opposite shows very nicely how constant competition and innovation has allowed successive US technology companies to come to the fore, to the undoubted benefit of us all.

Outside the above special circumstances, competition (like democracy) is far from perfect, but it is often the least bad of all the alternatives that have been tried. Put another way, the good thing about competition is that it isn't monopoly! The key attribute of a monopoly is that it confers freedom from challenge. This makes life comfortable for owners, managers and staff. But it weakens performance incentives and it weakens the pressure to innovate and try new ideas, allowing organisations to stick to routines and inefficient practices which ought to be abandoned. The chart opposite shows very nicely how constant competition and innovation has allowed successive US technology companies to come to the fore, to the undoubted benefit of us all.

But the competitive process is undoubtedly messy and beset with dead ends. Tim Harford puts it very well in his book Adapt:

'Few company bosses would care to admit it, but the market fumbles its way to success, as successful ideas take off and less successful ones die out. When we see survivors of this process ... we shouldn't merely see success. We should also see the long tangled history of failure, of all the companies and all of the ideas that didn't make it.'

And it is worth stressing that competing humans do not usually lose their humanity. Look at the camaraderie of athletes at the Olympic Games - when they are not in active competition. Competing industrialists can also often be perfectly friendly in social situations.

Competition, or 'market forces', or 'let the devil take the hindmost' cannot, however, be the whole story. Humans are social animals and there are altruistic elements in all of us. No economist or businessperson or politician should want or expect humans to be purely profit driven. Indeed, Adam Smith himself, in the opening words of his Theory of Moral Sentiments pointed out that:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrows of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous or the humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

One problem is that free (competitive) markets often fail to take account of the social costs that they impose on others - such as on the environment. That is why competition needs to be constrained by sensible environmental and other regulation. And let us not forget the huge costs that can be imposed on the rest of us by the failures in the financial markets that led to the 2008 financial crisis, and more recently to the problems associated with hyper-competition such as high frequency trading.

More important, perhaps, is the fact that, although competition is often the best way to ensure the lowest average prices and highest average service quality, it carries no guarantees about what particular outcomes will emerge, nor about which particular customers (or providers) will win or lose from the process. Disadvantaged individuals may therefore need to be protected by targeted regulation, whilst bearing in mind that this imposes a sort of tax on others - who may themselves not be very wealthy. (Energy regulation is a current example of this.)

Strong competition must also therefore be supplemented by ...

Consumer Protection

It is important to note that competing companies can sometimes behave very badly towards certain consumers. it is vital, therefore, that there is strong consumer protection legislation which is effectively enforced. Equally, consumers must not be over-protected from being able to make (what appear to outsiders to be) bad choices. Companies must be free to innovate in all sorts of ways, including offering products and packages which may not objectively appear 'better' than existing offerings. Click here for a deeper discussion of this subject.

Competition in Health, Education etc.

Competition in public services, such as health and education, is also heavily constrained by the following considerations:

- Expensive services (such as cancer treatments and university courses) have to be made available to the least well off in our society, not just those who can afford them.

- But the sharp elbows of the middle class often ensure that it is only the well-informed and/or the well-networked and/or the better off that can make full use of the ability to switch to a better school, or identify that excellent surgeon.

- The ability to choose a supplier has to be matched by there being a multiplicity of suppliers, which is hard to arrange in smaller towns and in rural areas

- There has to be sufficient spare capacity to accommodate transferring students and patients, and that spare capacity (under-used teachers, wards, doctors) has to be paid for by someone.

- Unsuccessful institutions have to be allowed to reduce capacity as they lose their students and patients - but that always runs into serious opposition, including from staff and from the students/parents and patients that remain.

- And the customer might not always be right. The doctor with the best bedside manner might not be familiar with the latest most effective treatments. The university that most effectively sells itself to 17 year olds might not employ the best teachers. Even more worryingly, its teachers might mark generously so as to avoid upsetting students whose opinions will be passed on to those thinking of following in their footsteps.

Public service competition therefore needs quite firm, clear and occasionally complex regulation if it is to offer net benefit.

Competition between Professionals

Competition can work in subtle ways, for instance amongst genuine professionals. One of the big gains from getting surgeons to publish their success rates etc. was that this encouraged them to learn from one another, and so good practice and promising new techniques spread much more quickly than in the past. The result was that most surgeons' performance came up to near the standard of the best, and patients did not need to 'exercise choice' even though that was the original headline reason for the publication of the data.

And it is important to bear in mind that professionals are nowadays much more specialised than they were in the past. There is still a role for the family solicitor, local accountant, and general practitioner (GP) doctor, but even their practices increasingly contain specialists such as legal conveyancers. And if you have anything like a serious problem, a good doctor or lawyer will very quickly transfer you to a true specialist, who will most likely be in a big teaching hospital or large international legal or accountancy firm. Much of the 'competition' that has in recent years been introduced into the National Health Service, for instance, has been aimed at ensuring that GPs do not feel obliged always to send their patients to a particular local hospital.

A sense of the change that is happening in medical general practice can be seen in this extract from a 2011 Kings Fund report which:

'highlights a number of challenges facing general practice, with demographic change, higher patient expectations and new technology changing the environment in which it operates. To meet these challenges, it encourages GPs and other primary care professionals to build on changes already taking place to transform the way general practice works by:

- accelerating the trend for practices to work as multi-professional teams, with GPs working closely with specialists and other professionals within and outside the practice delivering a 'new deal' for patients, which involves them much more closely in decisions about their care

- GPs moving from being 'gatekeepers' to 'navigators', co-ordinating care for people with complex needs, signposting patients to other public services and being held accountable for the quality of care provided

- accelerating the shift away from small practices working in isolation towards 'federated' networks of practices working more closely with one another and with other professionals

- practices looking 'beyond the surgery door' by focusing on prevention, taking a more active role in public health issues such as obesity, and reaching out to deprived communities.

The report also highlights the need to create a much stronger focus on quality improvement within general practice, with GPs taking responsibility for driving this forward based on:

- a much stronger commitment to transparency, with more information about quality of performance shared with patients, the public and fellow professionals

- a strong emphasis on peer review, with professionals benchmarking their performance and providing each other with challenge and support

- better use of information, data and information technology to monitor and measure quality, including a much stronger commitment to collecting and acting on patient feedback.'

Further Reading

I recommend Michael Grenfell's 2017 speech What Has Competition Ever Done For Us? and also Paul Geroski's essay: Is Competition Policy Worth It? - at pp 23-.

And the Centre for Competition Policy produced an interesting report in 2004 entitled The Benefits from Competition: some Illustrative UK Cases. It is a collection of six case studies which illustrate, in a non-technical way, the benefits of introducing competition into UK markets in which it had previously been absent or muted. It concludes in particular that:

- although competition can sometimes lead to substantial reductions in prices,

- and although government pro-competition policies are important,

- there also needs to be a pool of resourceful entrepreneurs capable of exploiting changed market conditions,

- because competition is not just about price - sometimes freeing up markets stimulates new ways of doing things which are unpredictable in advance but which turn out to be more important than mere price cuts.